3.2 Decide on an essential services package

A service package lists the services offered at each level of service delivery (community, primary care and hospital), and links to minimum requirements for staffing, medications and medical supplies.

While many countries have an existing services package, for emergency situations it is often necessary to define an essential services package. An essential services package should address the needs of children of different ages (Box 13) . It should be based on the priorities identified and the realities of service delivery constraints. The package should be defined as part of preparedness, put in place during response and expanded into a more comprehensive services package during recovery.

This section highlights important CAH considerations for an essential services package, in the following fields:

- acute conditions (general)

- chronic conditions (general)

- child safety and protection

- disease outbreaks and immunization

- nutrition and food security

- child development and education

- disability

- psychosocial distress and mental health

- sexual and reproductive health

- WASH.

For each field the important concepts and ideas that should be familiar to everyone working with children and adolescents in humanitarian emergencies are briefly described. Specific key actions and key indicators derived from existing standards are also given. Your interpretation and application of these actions and indicators will depend on your particular context and the priorities that you have identified. Depending on your role, some actions will be more directly relevant to you than others.

Box 13 Priority areas for children of different ages in humanitarian emergencies

Newborns (4). Biggest risks of death and morbidity are prematurity, sepsis (infection) and birth asphyxia, as well as small for gestational age and tetanus. Priority services must address safe birth, essential newborn care, care for small and sick newborns and prompt recognition and treatment of infection.

Young children (< 5 years). Biggest risks are respiratory infection, diarrhoea, measles and undernutrition, as well as meningitis (and other outbreaks). Priority services must address prevention and treatment of common infections (including immunization), nutritional deficiencies and child safety.

Older children (5–9 years). Biggest risks are infection, injury (including drowning, burns and traffic incidents) as well as mental health issues and nutrition. Priority services must address prevention and treatment of common infections and illness, chronic conditions, child safety and psychological well-being.

Younger adolescents (10–14 years). Biggest risks are injury, infection, mental health issues. Priority services must address safety and violence, sexual and reproductive health, treatment of common infections, chronic conditions and psychological well-being.

Older adolescents (15–19 years). Biggest risks are injury, infection, mental health issues and substance abuse, and pregnancy and childbirth. Priority services must address safety and violence, sexual and reproductive health, treatment for common infections, chronic conditions and psychological well-being.

NOTE: Many children’s services end at the age of 13 or 14 years, and adult-oriented services typically do not have a developmental perspective. Where age criteria for health services are unclear, using the older age limit is recommended.

Sections

Acute infections and injury are the leading causes of death in all age groups during humanitarian emergencies, and many have long-lasting effects (e.g. birth asphyxia, meningitis and trauma). This section focuses on common acute infections and neonatal conditions; other specific acute conditions are covered in later sections.

- Acute infections. Most deaths in humanitarian emergencies can be attributed to four conditions: diarrhoea, respiratory infections, measles and malaria.

- Reducing deaths from infection requires a coordinated, intersectoral response addressing health care access, supplies, communication, WASH, waste management, shelter and overcrowding, nutrition and food supply, outbreak detection and response, and vector control.

- Newborns (< 28 days of life) are at particularly high risk of death during emergencies because of poor antenatal care, maternal illness and/or undernutrition, and lack of safe birth options. Mothers may have poor access to maternity and obstetric care due to insecurity and displacement, destruction of existing facilities, or break down of usual services. Adolescent mothers and their babies are at particular risk.

- The main causes of neonatal death are: prematurity, infection and intrapartum complications (e.g. birth asphyxia).

- Most complications can be prevented or addressed by simple measures including: clean delivery and cord care, keeping the baby warm, skin-to-skin contact, supporting breastfeeding and monitoring for danger signs (i.e. complications that may result in death such as bleeding and hypertension).

Key actions – acute conditions (general)

Adapted from the Sphere Health Standards and the newborn health in humanitarian settings field guide (1,4)

- The RMNCAH/CAH working group (and organizations) develop and implement general prevention measures in coordination with relevant sectors. Priority areas are: safe water and hygiene, vector-borne infections, vaccine-preventable diseases, public safety, safe delivery, and recognition of illness in young children.

- Develop public health education messages to encourage people to seek care early for fever, cough, diarrhea, and obstetric and newborn complications (Section 1.4). Encourage antenatal, skilled birth, and postnatal care.

- Provide health care at all first-level health facilities (clinics/primary care) based on standard case management protocols. Use local protocols or international standards (e.g., see resources and tools at the end of this section), particularly IMNCI and basic emergency obstetric and newborn care. Provide skilled staff and essential supplies.

- Provide health care at hospitals (secondary/tertiary care) based on standard case management protocols. Use local protocols or international standards. Include comprehensive emergency obstetric and newborn care, emergency surgical care, and general pediatric care. Provide skilled staff and essential supplies.

- Implement triage, diagnostic, and case management protocols for early treatment of conditions such as pneumonia, malaria, diarrhea, measles, meningitis, undernutrition, dengue, and obstetric and newborn complications. Train staff on treatment protocols.

- Provide referral care for the management of severe illness. Establish communication and transportation systems (covering community, primary care, and hospitals) to manage common obstetric, newborn, and child emergencies.

Key indicators – acute conditions (general)

- The RMNCAH/CAH working group and partners have defined acute care priorities for newborns, children and adolescents. The RMNCAH/CAH working group and partners have advocated for these priorities within the health cluster and have successfully integrated them into the health cluster plan.

Chronic conditions of childhood are common. These conditions contribute substantially to the burden of disease and disability in all age groups, particularly older children and adolescents. This section covers common chronic health conditions. Mental health, other specific chronic health conditions and disability are covered later.

- Chronic conditions affect individuals, families, and the community. Effective support for those living with chronic conditions can substantially increase the ability of communities to cope with and respond to crises.

- Chronic conditions are defined as health conditions that last an extended period (> 3 months), cause considerable impact on the lives of the child and their family, and require particular health care services (37).

- Common chronic health conditions affecting children and adolescents include:

- Neurological: cerebral palsy, epilepsy

- Respiratory: asthma, cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis, chronic lung disease

- Cardiac: congenital heart disease, rheumatic heart disease

- Musculoskeletal: amputation, traumatic injury

- Endocrine: diabetes, hypothyroidism

- Nutritional: obesity/overnutrition, undernutrition

- Haematological/malignancy: sickle-cell disease, thalassemia, leukemia, lymphoma

- Developmental: intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, specific learning disorders

- Infectious: HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, scabies

- Sensory: blindness, deafness

- Psychological: anxiety, depression, trauma-response/post-traumatic stress disorder

- Congenital syndromes: Down syndrome, Turner syndrome, fragile X syndrome

- Humanitarian emergencies often destroy structures for the care of, and support for, children and adolescents with chronic conditions. Chronic conditions require different health system approaches from acute conditions, including close partnership between health providers, patients and families, and the broader community who provide support (Annex 4). Humanitarian emergencies can be an opportunity to improve chronic care systems by making use of resources provided during emergencies to establish a long-term system.

Key actions – acute conditions (general)

Adapted from the Sphere Health Standards and the newborn health in humanitarian settings field guide (1,4)

- The RMCAH/CAH working group and members cooperate with partners to ensure access to care for children and adolescents with chronic health conditions.

- Include children and adolescents living with chronic health conditions, and their families, in planning. Promote independence and self-management, recognizing that children and adolescents and their families as the experts in care.

- Assess and document the prevalence of chronic health conditions and disability and share the data with agencies responding to the disaster. Include the prevalence of chronic health conditions and disability in needs assessment and monitoring and evaluation.

- Identify individuals with chronic health conditions who were receiving treatment before the emergency and ensure that they continue to do so. Avoid sudden discontinuation of treatment.

- Ensure that people with acute complications and exacerbations of chronic health conditions that pose a threat to their life and individuals in pain receive treatment.

- In situations where treatments for chronic conditions are unavailable, establish clear standard operating procedures for a referral.

- Ensure that essential diagnostic equipment, core laboratory tests, and medication for the routine, ongoing management of chronic conditions are available through the primary health care system. This medication must be specified on the essential medicines list.

Key indicators – chronic conditions

- The RMNCAH/CAH working group has identified priority chronic care needs, essential medicines and medical supplies, and communicated these to providers, in collaboration with the health cluster.

- Health facilities have adequate medication for people who were receiving treatment for chronic conditions before the emergency to continue receiving this medicine.

Child protection is core business for all those who work with children and adolescents during humanitarian emergencies.

- Unintentional injuries. Globally, these injuries account for over 30% of deaths in young adolescents aged 10–14 years and almost 50% in older adolescents aged 15–19 years. In humanitarian settings, the risk of children and adolescents being unintentionally injured (e.g., falls, drownings, burns, and road traffic injuries) is increased by rapid environmental changes, such as overcrowding, displacement, reconstruction, and disruption to fuel supplies, housing, and sanitation.

- Conflict. Three quarters of the people killed in recent conflicts around the world have been women and children. Explosive remnants of war, landmines, and crossfire cause a considerable number of injuries to children and adolescents, both unintentionally and intentionally. Limited access to health care may delay treatment for illnesses and injuries leading to a greater chance of long-term or permanent injury.

- Violence. Violence and child abuse may increase after a disaster, both within families and outside the home. During conflicts, children and adolescents may suffer extreme violence such as killing, maiming, torture, and abduction. Apart from the acute and chronic physical effects of violence, it often has long-term psychosocial impacts on survivors.

- Sexual and gender-based violence. Sexual violence, often concealed, occurs in all emergency contexts. The consequences of sexual violence include physical injuries and death, unwanted pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, mental health issues, distress, and social and economic exclusion. In addition, harmful practices such as early marriage or female genital mutilation can increase after a humanitarian disaster.

- Other protection concerns. During a humanitarian crisis, children and adolescents are more likely to join labor forces – voluntarily and involuntarily. They are particularly vulnerable to unsafe working environments, exploitation, and trafficking. Children and adolescents may be recruited into armed forces, where the risks of abuse, drug addiction, violence, and injury are extremely high. Law and order may break down during humanitarian emergencies, and adolescents in the justice system are at particular risk of maltreatment.

Key actions – child safety and protection

Adapted from the child protection standards of the Child Protection Working Group (38)

- The RMNCAH/CAH working group should cooperate with the protection cluster lead to ensure child safety actions are integrated into the humanitarian response of every sector. Use emergencies as an opportunity to strengthen child protection systems for the long term, and raise awareness of child protection issues and sociocultural responses.

- Contribute to protection cluster activities and encourage CAH partners to develop appropriate child safety and protection policies and procedures:

- Develop an advocacy plan that respects diversity, inclusion, privacy, and children’s agency. Advocate with governments, donors, parties involved in the conflict, those planning and implementing programs in other sectors, and other high-level actors and decision-makers.

- Involve children and adolescents, particularly those with disabilities and other vulnerabilities, in developing and implementing responses.

- Implement risk assessment, risk reduction, and injury prevention in all humanitarian activities.

- Map existing protection services. Develop the capacity of child protection workers and all health and humanitarian workers to prevent, detect, and respond appropriately to child protection issues.

- Establish case management services to identify and refer children at high risk to essential services, including medical support, interim care, psychosocial support, legal assistance, safety, and security.

- Ensure organizations have codes of conduct, hold staff to high standards, deal appropriately with staff misconduct with children and adolescents, actively gather complaints, and address allegations transparently.

- Ensure services are gender-sensitive and culturally appropriate.

- Create safe community spaces, playgrounds, and recreation areas for children and adolescents. Strengthen/reactivate existing supportive community networks to prevent harm and promote well-being.

- Develop plans for how your agency will cooperate with partners to support the most at-risk children and adolescents:

- Sexual violence. Recognize that sexual violence is common. Seek to understand local perceptions and reactions. Disseminate sexual violence prevention messages. Educate health and allied staff to look, recognize, and respond to sexual violence sensitively. Report information in line with national laws and international norms. Consider using the Inter-Agency Child Protection Information Management System (39) or the Gender-Based Violence Information Management System (40).

- Armed forces. Assess involvement of children and adolescents in armed forces, community perceptions, and demobilization and reintegration activities. Support schools and other institutions protecting children. Share prevention, reporting, and survivor care information.

- Survivors. Develop age-appropriate survivor assistance that includes medical care, physical rehabilitation, psychosocial support, legal support, economic inclusion, and educational and social inclusion. Include non-stigmatizing support for those who need additional attention (e.g., those involved in armed forces, pregnant girls, sexually exploited children and adolescents, girls who are pregnant as a result of rape).

- Child labour. Prioritize action on the worst forms of child labour, including forced/bonded labour, armed conflict, trafficking, sexual exploitation, illicit work, unsafe work. Involve affected families and other local stakeholders in responses.

- Unaccompanied and separated children. Assume all children have a caring adult with whom they can be reunited, until tracing proves otherwise. Review existing legal systems and procedures for family tracing and reunification. Assess the scope, causes, and risks of family separation. Take practical steps to prevent separation (e.g., reception registers, ID cards). Avoid unintentionally encouraging abandonment (e.g., advertising special assistance to unaccompanied and separated children).

- Justice system. Strengthen child-friendly spaces in courts and police stations. Identify children in detention (especially arbitrary detention), and patterns of violations. Promote diversion activities to resolve issues without the trauma of the justice system.

Key indicators – child safety and protection

- The RMNCAH/CAH working group and partners have developed and adopted child safety and protection measures within their organizations.

- The RMNCAH/CAH working group works collaboratively with the protection cluster to support full integration of child safety into humanitarian action.

Disease outbreaks are the greatest immediate threat to life during humanitarian emergencies, making immunization and other preventative measures a critical priority for all age groups.

- Measles is a major cause of death, particularly in situations of displacement, crowding and undernutrition. While most deaths occur in young children (under 5 years), a significant proportion of deaths occur in older age groups and full immunization coverage is essential for population protection.

- Other important vaccine-preventable infections include: cholera, meningitis, yellow fever, polio, tetanus, diphtheria and pneumococcal infections.

- All sectors must cooperate to assess risks, monitor for and detect outbreaks, and mount a multisector response (including immunization, water and sanitation, communication and supply chain).

Key actions – outbreaks and immunization

Adapted from the Sphere Health Standards (1). See Standards for details

Disease outbreaks: The RMNCAH/CAH working group and partners:

- Assist the health cluster to prepare an outbreak investigation and response plan, in collaboration with other clusters.

- Implement appropriate vector-control methods for malaria, dengue, and other vector-borne diseases depending on local epidemiology.

- Implement disease-specific prevention measures, e.g., mass vaccination against measles as indicated.

- Establish a disease early warning surveillance and response system based on a comprehensive risk assessment of communicable diseases, as part of the broader health information system. See action area 4 on monitoring, evaluation, and review.

- Train health care staff and community health workers to detect and report potential outbreaks.

- Provide populations with simple information about symptoms of epidemic-prone diseases, as well as about where to go for help.

- Ensure that protocols for the investigation and control of common outbreaks, including appropriate treatment protocols, are available and distributed to relevant staff.

- Ensure that reserve stocks of essential medicines and supplies are available for priority diseases or can be procured rapidly from a pre-identified source.

- Identify sites for isolation and treatment of infectious patients in advance, e.g., cholera treatment centers.

- Identify a laboratory, whether local, regional, national, or in another country, that can confirm outbreaks.

- Ensure that sampling materials and transport media are available on-site for the infectious agents most likely to cause a sudden outbreak.

- Describe the outbreak according to time, place, and person, so as to identify high-risk individuals and adapt control measures.

Immunization

- Estimate measles vaccination coverage of children aged 9 months to 15 years at the outset of the disaster response to determine the risk of outbreaks.

- When measles vaccination coverage is less than 90% or unknown, conduct a mass measles vaccination campaign for children aged 6 months to 15 years, including the administration of vitamin A to children aged 6–59 months.

- Ensure that all infants vaccinated between 6 and 9 months of age receive another dose of measles vaccine on reaching 9 months.

- For mobile or displaced populations, establish an ongoing system to ensure that at least 95% of newcomers to a camp or community aged between 6 months and 15 years receive vaccination against measles.

- Address potential challenges to the cold chain and vaccine supplies.

- Consider reactive or pre-emptive vaccination for certain communicable diseases against imminent or ongoing outbreaks. These communicable diseases are cholera, measles, meningitis, yellow fever, and polio.

- Re-establish the national immunization program (Expanded Program on Immunization) as soon as conditions permit to routinely immunize children against measles and other vaccine-preventable diseases included in the national schedule.

- Screen children attending health services for vaccination status. Administer any needed vaccinations.

Key indicators – outbreaks and immunization

- The RMNCAH/CAH working group and partners have contributed to the creation and dissemination of the multisector outbreak response plan.

- The RMNCAH/CAH working group and partners support the re-establishment of the national immunization programme.

- Percentage of reported outbreaks investigated within 48 hours of alert: 90%.

- Percentage of target populations that successfully received the interventions, following a vaccination campaign:

- Measles – 95% of children aged 6 months to 15 years.

- Vitamin A – 95% of children aged 6–59 months.

- Case fatality rate of measles: Aim for less than 5% in conflict settings.

- The national immunization programme has been re-established:

- 100% enrollment of infants in national immunization programmes.

- 90% of children aged 12 months have had three doses of the diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus vaccine.

- 90% of primary health care facilities offer basic services within the immunization programme at least 20 days a month.

In emergencies, increased illness and irregular access to nutritious foods, adequate shelter, water, hygiene and sanitation dramatically increases the incidence of acute undernutrition. Rates of undernutrition and related mortality can increase sharply during a humanitarian crisis.

- Globally, more than a third of all deaths in children under 5 years are attributable to undernutrition, either as a direct cause of death or through the weakening of the body's resistance to illness. A young child with severe acute malnutrition is nine times more likely to die than a well-nourished child.

- Undernutrition is a particular threat to child survival during an emergency. Population displacement, break down of food supply chains, disruption to local crops and food production, and issues with cooking fuel and energy sources, privacy and sanitation can all lead to an inadequate availability of food.

- Breastfed children are at least six times more likely to survive in the early months, so support, promotion and protection of breastfeeding are fundamental to preventing undernutrition and death in infants in emergencies.

- Undernutrition survivors can experience long-term consequences on their cognitive, social, motor skill, physical and emotional development.

- For children and adolescents, micronutrient deficiency increases the risk of death from infectious disease and impaired physical and mental development. Maternal micronutrient deficiency during pregnancy and breastfeeding also increases the risk of poor health and development in children. Provision of fortified foods and micronutrient supplements is an integral component of the response to tackle micronutrient deficiency.

Key actions – nutrition and food security

Adapted from the Sphere Health Standards (1). See Standards for full actions and details

General

- The RMNCAH/CAH working group and partners support the nutrition cluster lead to assess, plan, and implement preventative and curative programs addressing priority nutrition needs.

- Assess the nutrition and food security status of local communities to identify those most affected and to define the most appropriate response.

- Analyze available cooking methods, including the type of stove and fuel used. Identify related risks that threaten safety and leave people vulnerable to harm, particularly women and girls.

- Consult with local communities and across sectors to identify local needs and groups with the greatest nutritional support needs.

- Evaluate national and local capacity to lead and support the response.

Severe acute malnutrition

- Establish clearly defined and agreed malnutrition strategies, including criteria for the set up and closure of inpatient and outpatient interventions. Include inpatient care, outpatient care, referral, and community components.

- Maximize access to and coverage of severe acute malnutrition interventions through community engagement from the beginning of the response.

- Emphasize protecting, supporting, and promoting breastfeeding, complementary feeding, and hygiene. Admit breastfeeding mothers of acutely malnourished children under 6 months to inpatient facilities to provide supplemental feeding for the child.

- Provide nutritional and medical care according to nationally and internationally recognized guidelines for community management of acute malnutrition for the management of severe acute malnutrition.

Micronutrient deficiencies

- Determine the most common micronutrient deficiencies.

- Train health staff on how to identify and treat micronutrient deficiencies.

- Provide micronutrient supplements as necessary:

- Consider vitamin A, iron, and folic acid, and iodine in children aged 6–59 months.

- Provide daily supplements to pregnant and breastfeeding women.

Infant and young child feeding in emergencies

- Establish policies and programming for infant and young child feeding in emergencies and a coordination authority.

- Mitigate and manage potential risks associated with inappropriate donations of breastmilk substitutes (formula milk) and associated equipment.

- Prioritize pregnant and breastfeeding women for access to food, cash or vouchers, and other supportive interventions. Enable access to skilled breastfeeding counseling for pregnant and breastfeeding mothers.

- Support timely, safe, adequate, and appropriate complementary feeding.

- Provide feeding support to particularly vulnerable infants and young children:

- Infants and young children with HIV.

- Separated and unaccompanied infants and young children.

- Low birth weight infants and young children.

- Infants and young children with disabilities.

- Infants and young children under 2 years of age not breastfeeding.

- Acutely malnourished infants and young children.

Key indicators – nutrition and food security

- The RMNCAH/CAH working group and partners have supported the nutrition cluster lead to assess, plan, and implement preventative and curative programmes.

- Number of systematic and objective food security needs assessments conducted within the first week of an emergency response: at least one, with clear recommendations.

- Percentage of targeted households that report that provision of food assistance corresponds to their requirements: establish a baseline and move towards improvement.

- Standard assessment and analysis methodologies adopted:

- Single standard methodology adopted for each nutrition response.

- All reports contain clear recommendations to meet prioritized needs.

- Population proximity to dry ration supplementary feeding sites:

- More than 90% of the target population can access dry ration feeding within a day.

- More than 90% of the target population can access on-site programs within an hour.

- Feeding program outcomes (died, recovered, and defaulted):

- Died: less than 3%.

- Recovered: over 75%.

- Defaulted: less than 15%.

- National/organizational policies address infant and young child feeding in emergencies:

- During preparedness or within 4 weeks of the start of the emergency.

- Lead agency designated within 72 hours of the start of the emergency.

- Prevalence of undernutrition in children under 5 years disaggregated by sex and age (from 24 months on, also disaggregated by disability): use WHO classification system (global acute malnutrition less than 15%).

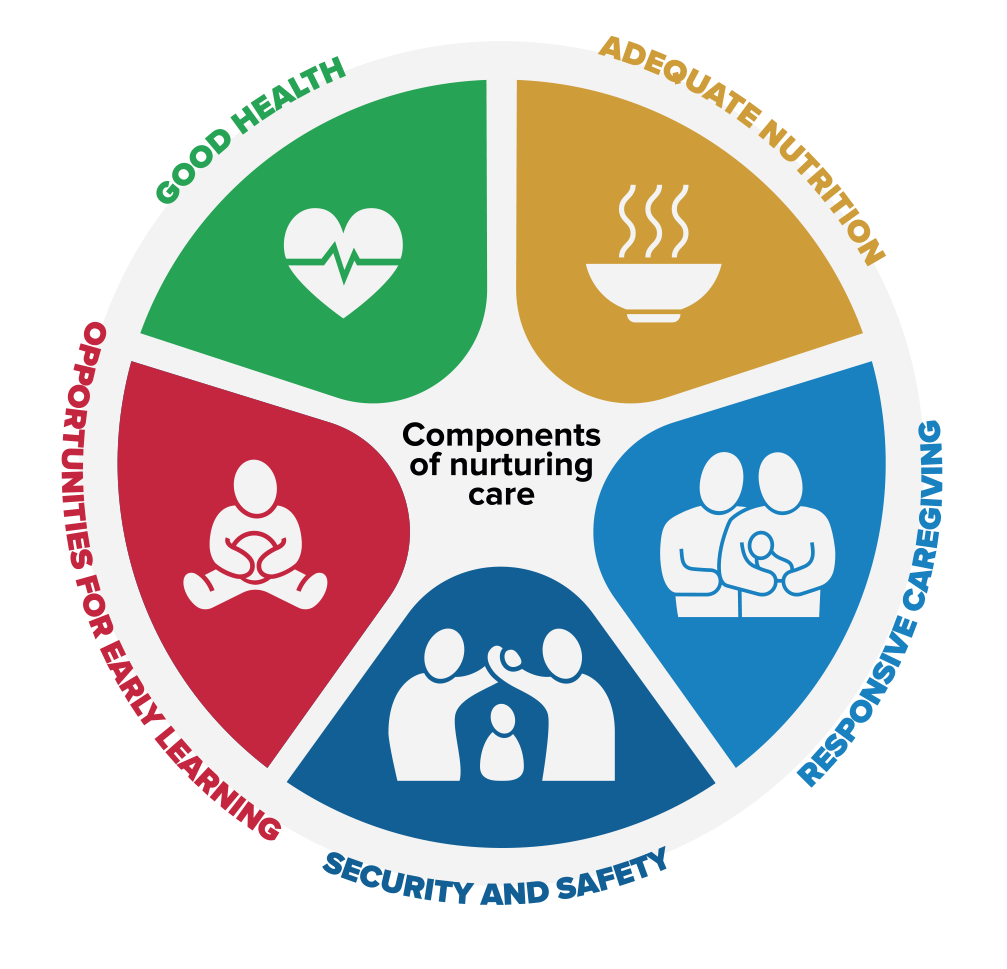

Nurturing care is essential for child development (Fig. 10). Early childhood development should be integrated into all humanitarian activities .

- Humanitarian emergencies can threaten all the components of nurturing care because they can lead to, for example, unsafe environments, lack of nutrition, and caregivers who are absent or unable to attend to and stimulate young children. This leads to toxic stress, which disrupts the developing brain’s architecture.

- Conversely, efforts to improve infant attachment, sense of security and early stimulation can be enormously protective for children in crisis.

- Responsive caregiving is particularly important during emergencies, and parents need support to prioritize young children’s development alongside other critical competing priorities.

Particular aspects of nurturing care are covered in other sections (e.g. child safety and protection, nutrition and food security). See UNICEF’s Early childhood development in emergencies: integrated programme guide (42) for more details.

Education is particularly important throughout early childhood and adolescence. We know that communities value and prioritize education during emergencies, recognizing its life-sustaining and life-saving role.

- Education and early learning opportunities are critical to the development and well-being of children and adolescents, especially during humanitarian emergencies. Education provides physical, psychosocial and cognitive protection.

- Education can enable early identification of children at risk (e.g. child head of household, impoverished children and undernourished children) and those with additional needs.

- Education can protect children and adolescents from dangers and exploitation (e.g. sexual or economic exploitation, early marriage, and involvement in armed forces and crime).

- Education provides children and adolescents with problem-solving and critical-thinking skills, which enable them to make more informed decisions and better understand political messages and conflicting information.

- Educational venues can provide a place to deliver essential support such as food and nutritional supplements, WASH education and resources, health education and health services (e.g. immunization, deworming and menstrual care).

- Education can promote inclusion and equality if it provides equitable access for groups at high risk.

- Education can provide an important routine to support well-being and recovery.

Fig. 10 Nurturing care framework (43)

Key actions – child development and education

- The RMNCAH/CAH working group and partners work with the education and other sectors to integrate nurturing care for all children (from early childhood care to post-secondary education) into humanitarian action. (See Annex 5 and Annex 6 for more on early child development and education in emergency situations.)

- Share health promotion messages. Share information on health challenges and health service delivery (e.g., access barriers, unreached populations, and emerging health issues). Strengthen referral pathways for children and adolescents with additional health needs.

Key indicators – child development and education

- The RMNCAH/CAH working group and lead education cluster agency have regular meetings to strengthen coordination of activities.

Disability is as an umbrella term for impairments, limitations to activities and restrictions on participation.

Disability is the interaction between individuals with a health condition (e.g. cerebral palsy, Down syndrome and depression) and personal and environmental factors (e.g. negative attitudes, inaccessible transportation and public buildings, and limited social supports). (44)

Humanitarian agencies can, and should, provide humanitarian action that is inclusive of and appropriate to children and adolescents with disabilities. Chronic health conditions were addressed in section 3.2.2. This section on disability focuses on the structural aspects of disability-inclusive humanitarian action.

- Children and adolescents with disabilities are often forgotten by service planners and implementers, resulting in services that are inaccessible to them and inappropriate to their needs. A disability-inclusive approach must be part of all stages of humanitarian planning, delivery, and monitoring and evaluation.

- Children and adolescents with disabilities are at particular risk when their coping strategies and usual supports are weakened. For example, loss of assistive devices (e.g. hearing aid, glasses and mobility aids), medications or medical supplies (e.g. sanitary items, feeding tubes and catheters), loss of caregiver or support person(s), poor access to medical services, and loss of financial or other social supports.

- Children and adolescents with disabilities may be unable to access mainstream humanitarian services or food distribution (either directly due to their impairment or due to associated social stigma and negative attitudes).

- Children and adolescents with disabilities are particularly at risk of physical, sexual, emotional and verbal abuse and neglect.

Children with disabilities … belong at the centre of efforts to build inclusive and equitable societies – not only as beneficiaries, but as agents of change. After all, who is in a better position to comprehend their needs and evaluate the response”? (45)

Key actions – disability

Adapted from the Sphere Health Standards (1)

- The RMNCAH/CAH working group and lead education cluster agency have regular meetings to strengthen coordination of activities.

- The RMNCAH/CAH working group and partners promote disability-inclusive approaches in all activities (see Annex 7):

- Use a disability-inclusive approach to humanitarian response.

- Ensure information is accessible to persons with disabilities, particularly those with visual, hearing, or language impairments.

- Make mainstream services accessible through planning and design (health, WASH and nutrition services, and schools).

- Include children and adolescents with disabilities, and their families, in planning. Promote independence and self-management, recognizing that children and adolescents and their families are the experts in care.

- Ensure that assistive devices (e.g., walking aids) are available for people with mobility or communication difficulties.

- Challenge discriminatory attitudes and promote equity by partnering with disability organizations at the community, local, and national level.

Key indicators – disability

- All health care providers and partner agencies have adopted policies on disability-inclusive action, and are translating these into concrete actions.

- Humanitarian emergencies expose children and adolescents (and their carers) to a wide range of psychosocial traumas, including displacement, housing instability, resource and food insecurity, death, family separation, physical injuries and illness, armed violence, abuse, neglect and exploitation. The lack of credible or accurate information for those affected by an emergency exacerbates confusion and insecurity.

- Emergencies weaken protective familial and community supports for children and adolescents, increasing the risks of a wide range of psychosocial problems, and exacerbate pre-existing problems.

- Children and adolescents of different ages are all at risk. They may express their distress in a variety of ways, including developmental regression, anxiety, sleep problems, emotional changes, risk-taking, substance misuse, impaired concentration, and changes in behaviour in and out of school.

- Alcohol and other drugs can become an important problem, particularly among those involved with armed forces.

- Many children and adolescents have experienced substantial loss and need support through grief and bereavement.

- Some children and adolescents are more at risk, especially those who have lost their usual supports, or who are survivors of violence. Emergency situations can unmask, trigger or exacerbate serious mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress disorder.

The core principles of emergency mental health and psychosocial interventions are (46):

- Promote respect for human rights and equity

- Promote community (adolescent) participation

- Do no harm

- Build on available resources and capacities

- Integrate activities and programming into wider systems (e.g. health programmes and education programmes)

- Develop a multilayered response

Key actions - psychosocial and mental health

Adapted from the Child protection standards of the Child Protection Working Group (38)

- The RMNCAH/CAH working group and partners work with child protection, education, and other sectors to promote good mental health and well-being.

- Ensure the availability of basic clinical mental health care for priority conditions (including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder) at every health facility.

- Provide psychological interventions for people with prolonged distress and disabling emotional problems.

- Protect the rights of people with severe mental health problems in the community, hospitals, and institutions (e.g., schools and the workplace).

- Minimize harm related to alcohol and drugs through health promotion, confronting stigma, and non-punitive health care and support for those affected.

- Ensure psychosocial support is available for national workers involved in the emergency response.

- Strengthen pre-existing community networks to provide psychosocial support to children and adolescents and their families; for example, by providing information on how to cope with stress and carrying out activities for children.

- Support activities for children and adolescents in the community, such as recreational activities, sports, cultural activities, and life skills, to help recreate a routine and help them build their resilience.

- Provide support to caregivers to improve care for their children, to deal with their own distress, and to link them to basic services.

Key indicators – psychosocial and mental health

- The RMNCAH/CAH working group and partners have identified mental health priorities for children, adolescents, and their carers and families, in collaboration with the health cluster.

- Basic mental health services are available at every facility.

Sexual and reproductive health issues affect children of all ages, and good care can have a considerable effect both immediately and in the longer term.

- Adolescents need culturally sensitive information and resources to protect their sexual and reproductive health.

- Children and adolescents are particularly at risk of sexual exploitation, rape and gender-based violence, including child and forced marriage, and genital mutilation. Survivors need adolescent-friendly medical, psychological, social and legal care.

- The well-being of young parents directly affects the health of their offspring.

- Poor nutrition and risk-taking behaviours, including drug and alcohol abuse, can complicate these health issues.

- Pregnant adolescents are at increased risk of morbidity and mortality from complications during pregnancy and childbirth, including obstructed labour, preterm labour and spontaneous abortion.

- Half of new HIV infections occur in young people aged 15–24 years, and a third of new cases of curable sexually transmitted infections affect people younger than 25 years.

- Five million adolescents between the ages of 15 and 18 years have unsafe abortions each year causing 70 000 abortion-related deaths. The unmet need for contraceptives among adolescents is more than twice that of married women.

During a crisis, children and adolescents are at higher risk of:

- Early pregnancy

- Unmet need for contraception and unwanted pregnancy

- HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted infections

- Unsafe abortion

- Sexual and gender-based violence (in all forms)

- Difficulties with the management of menstrual hygiene.

Key actions - sexual and reproductive health

Adapted from the Minimum Initial Service Package (MISP) for Reproductive Health and Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health Toolkit for Humanitarian Settings (47,48)

General

- The RMNCAH/CAH working group and partners collaborate to assess, plan and implement services based on identified priorities. Encourage adolescent participation in any multisectoral prevention task force.

- Establish basic services at the outset of a crisis and progress towards more comprehensive services. (See MISP for lists of basic and comprehensive services.)

- Provide community information, education and communication directed toward adolescents. Involve adolescents, parents and community leaders in the development of an information, education and communication strategy.

- Train staff in and provide adolescent-friendly care for all listed services.

- Collaborate across humanitarian clusters and community groups to establish education and referral services.

- Source and procure contraceptive supplies and ensure availability to meet demand.

- Train community workers to provide community-based family planning services, including counseling and health education.

Address gender-based violence in adolescence

- Address gender-based violence in adolescence

- Coordinate and ensure health sector prevention of sexual violence.

- Prevent and tackle other forms of gender-based violence, including domestic violence, forced and/or early marriage, female genital mutilation, and trafficking.

- Provide medical, psychological, social and legal care for survivors of gender-based violence and sexual violence.

- Work with the protection cluster and subcluster for gender-based violence to identify a multisectoral referral network for young survivors of gender-based violence.

- Raise awareness in the community about the problem of gender-based violence and sexual violence, strategies for prevention and care available for survivors.

- Engage community health workers to link young survivors of sexual violence to health services.

- Sensitize uniformed men about gender-based violence and its consequences.

- Establish peer support groups.

Establish maternal and newborn care services that address the needs of adolescents

- Address gender-based violence in adolescence

- Establish maternal and newborn care services that address the needs of adolescents

- Establish a round-the-clock referral system for obstetric emergencies.

- Provide midwife delivery supplies, including newborn resuscitation supplies.

- Provide clean delivery packages.

- Provide adolescent-friendly services at health facilities, involving male partners where appropriate.

- Coordinate with the health cluster and other sectors to identify pregnant adolescents in the community and link them to health services.

- Engage community health workers to link young mothers to health services.

- Encourage facility-based delivery for all adolescent mothers.

- Integrate mental health and psychosocial support services for adolescent mothers.

Address sexually transmitted infections in adolescents, including HIV prevention and treatment

- Address sexually transmitted infections in adolescents, including HIV prevention and treatment

- Provide access to free condoms. Provide discreet access to free condoms at adolescent-oriented distribution points.

- Ensure adherence to standard precautions and safe blood transfusions.

- Establish comprehensive prevention and treatment services for sexually transmitted infections, including surveillance systems for sexually transmitted infections.

- Provide care, support and treatment for people living with HIV. Make HIV treatment available for people already taking antiretroviral medicines, including for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV.

- Train adolescents on community-based distribution of condoms. Provide education on the prevention of and testing for sexually transmitted infections and HIV and the treatment services available. Provide referrals for services.

- Establish programs, including peer education, for adolescents most at risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV.

Key indicators – sexual and reproductive health

- The RMCAH/CAH working group and partners have created and communicated a plan to address sexual and reproductive health issues across the lifespan.

- Gender-based violence programs have been established, and referral pathways for children and adolescents are available and appropriate.

- All services, including obstetric and maternity services, are adolescent friendly.

- Outbreaks of diarrhoeal diseases, including dysentery and cholera, are common in emergencies. Faecal–oral diseases may account for more than 40% of deaths in the acute phase of an emergency, and more than 80% of deaths in children under 2 years. In some emergencies and post-emergency situations, diarrhoea can be responsible for most deaths.

- Overcrowded WASH facilities can be a considerable threat to children’s safety because this situation may lead to, for example, riots, demonstrations, violent behaviour and child abuse. In addition, families may adopt risky strategies to obtain water, sanitation facilities, or soap and buckets.

- WASH implementation may enable children and adolescents, especially girls, to attend school. WASH programmes can free children and adolescents from the hard work of water collection and hygiene maintenance (this includes enabling girls to manage menstrual hygiene with dignity).

- Children need different excreta disposal facilities depending on age. If nappies (diapers) are distributed, waste management is an issue; however, non-disposable nappies present the problem of washing. Providing potties (pot toilets) for children may be useful if children are afraid of falling into a pit latrine or when they might not want to use a toilet because of fear of the dark or snakes and other animals, or because of the smell and dirtiness.

- Young women and girls are often responsible for managing the water needs of the family and maintaining domestic hygiene. Their safe access is an essential consideration when designing refugee shelter and WASH facilities (latrines, water sources and lighting). Considerations include placement (relative to living quarters) of sanitation (or water source), shared or collective sanitation facilities versus individual, and amenities (lighting, locks and other design elements). Safe, hygienic and private options for menstrual hygiene management should be provided.

- People with disabilities or chronic health conditions should also be considered and their needs for WASH access evaluated and provided.

The main objective of WASH programmes in humanitarian settings is to reduce the risk of faecal–oral diseases and exposure to vectors that can carry disease. This is achieved through the:

- promotion of good hygiene practices

- provision of safe drinking water

- reduction of environmental health risks

- provision of conditions that allow people to live with health, dignity, comfort and security.

Key actions - WASH

Adapted from the Sphere WASH standards (1). See Sphere Standards for detail

General

- The RMNCAH/CAH working group and partners collaborate with the WASH cluster leads to support holistic WASH programmes.

- Implement WHO’s WASH facility improvement tool for health facilities (49).

- Consult local communities and stakeholders (including adolescents, children with disabilities, women, and hard-to-reach groups or those at high risk) to identify the key WASH risks, needs, and coping mechanisms. Seek ongoing feedback.

- Determine the main public health threats to the affected population, for example, excreta management, vectors, handwashing, and infrastructure. Assess current behaviors and practices in the affected population. Train communities to monitor and provide feedback on WASH disease incidence and risk behaviors.

- Hygiene promotion. Communicate with families about children’s WASH needs:

- Wash hands with soap after fecal contact and before preparing food, eating food, or feeding children.

- Treat drinking water with an appropriate household water treatment method before giving it to children.

- Freshly prepare children’s food or reheat it to boiling before feeding.

- Protect children from ingesting soil and animal feces.

- Hygiene. Consult with the community to understand the hygiene items they require (e.g., soap, menstrual hygiene products, incontinence products, nappies, potties, and water containers). Develop appropriate menstrual hygiene and incontinence solutions (e.g., toilets, bathing areas, laundry facilities, disposal options, and water supply).

- Water supply. Define the most appropriate structures and systems for short- and long-term management of the water systems and infrastructure.

- Excreta management. Determine the most appropriate excreta management options. Consult all stakeholders about the siting and design of shared toilets. Design and construct toilets to minimize safety threats, especially for women, children, older people, or people with disabilities.

- Segregate all shared toilets by sex and age, considering cultural norms and the potential for violence, harassment, or stigmatization.

- Ensure that toilets used by women and girls have facilities to let them manage menstrual hygiene, including a menstrual waste disposal option.

- Facilities at schools, temporary learning spaces, child-friendly spaces, and women’s and girls’ safe spaces need to be planned, designed, and constructed with those specific users in mind.

- Solid waste. Work with communities to manage solid waste systems and ensure a clean environment to live, learn, and work.

- Vector control. Work to protect communities, families, and individuals from a range of relevant vector-borne diseases.

Key indicators – WASH

- The RMNCAH/CAH working group and partners have contributed to the WASH sector plan and regularly meet to support program implementation.

- Percentage of the affected population that has hygiene items suitable for their priority needs:

- 100%

- Percentage of the affected population (households) using soap and water (or an alternative) for hand washing:

- 100%; 250 g soap per person per month.

- Percentage of women and girls, and people with incontinence, that express satisfaction with the consultation regarding the design of menstrual hygiene management systems, including toilets and disposal options:

- 100%

- Number of liters of water per person per day accessible for drinking and domestic and personal hygiene:

- 15 L per person per day (based on cultural and social norms, the context and phase of response, and in coordination with national authorities and/or cluster members).

- Percentage of affected households that possess at least two clean narrow-necked and covered water containers for drinking water at all times (100%).

- Percentage availability of appropriate, accessible, and safe toilets.

- Percentage of health facilities appropriately disposing of hazardous waste.