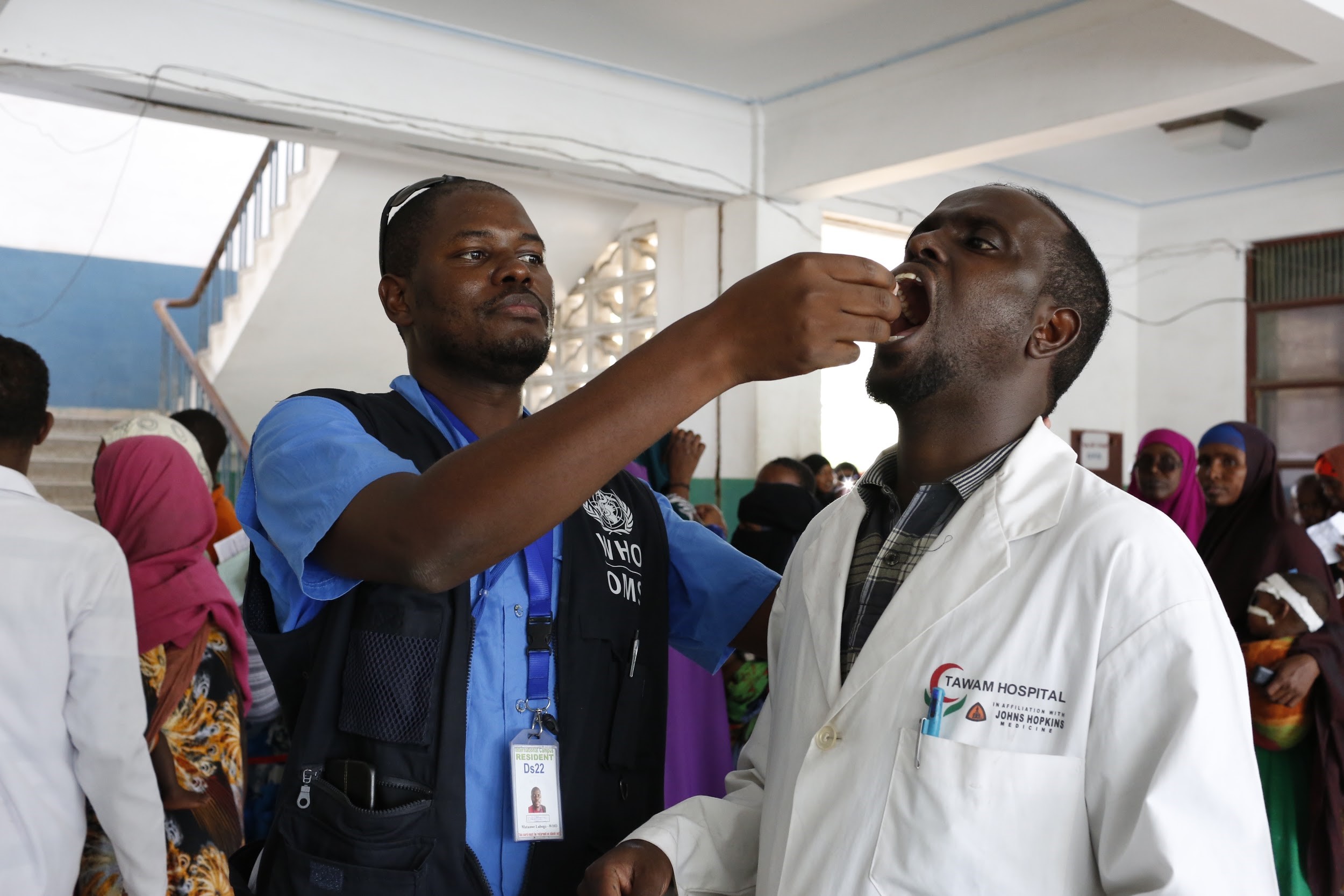

Dr. Mutaawe Lubogo (l) administering the Oral Cholera Vaccine to a health worker during the 2017 campaign (Photo: WHO)

Dr. Mutaawe Lubogo (l) administering the Oral Cholera Vaccine to a health worker during the 2017 campaign (Photo: WHO)

When Dr Mutaawe Lubogo speaks about his work, enthusiasm colors his voice and a sparkle lights his eyes. Dr Lubogo, a cholera expert working with WHO in Somalia, is passionate about the fight against infectious diseases in the country. “Mention an epidemic, and find it in Somalia”, he says. “People face outbreaks of cholera, diphtheria, dengue - and that’s just in the parts of the country which are safe enough to visit, where we know what’s going on. There may be other diseases in inaccessible areas.”

In Somalia, Dr Lubogo says, almost two thirds of the population has not had access to modern health services for the past 30 years. The ongoing civil war has severely damaged Somalia’s health services. It destroyed hospitals and health centers, forced medical professionals to flee danger, and broke down supportive infrastructure like roads and communications services. In addition, the majority of the country faces an annual cycle of flooding and severe droughts, which in turn drives food insecurity, famine, and mass migration. Dire conditions which provide a fertile breeding ground for infectious diseases.

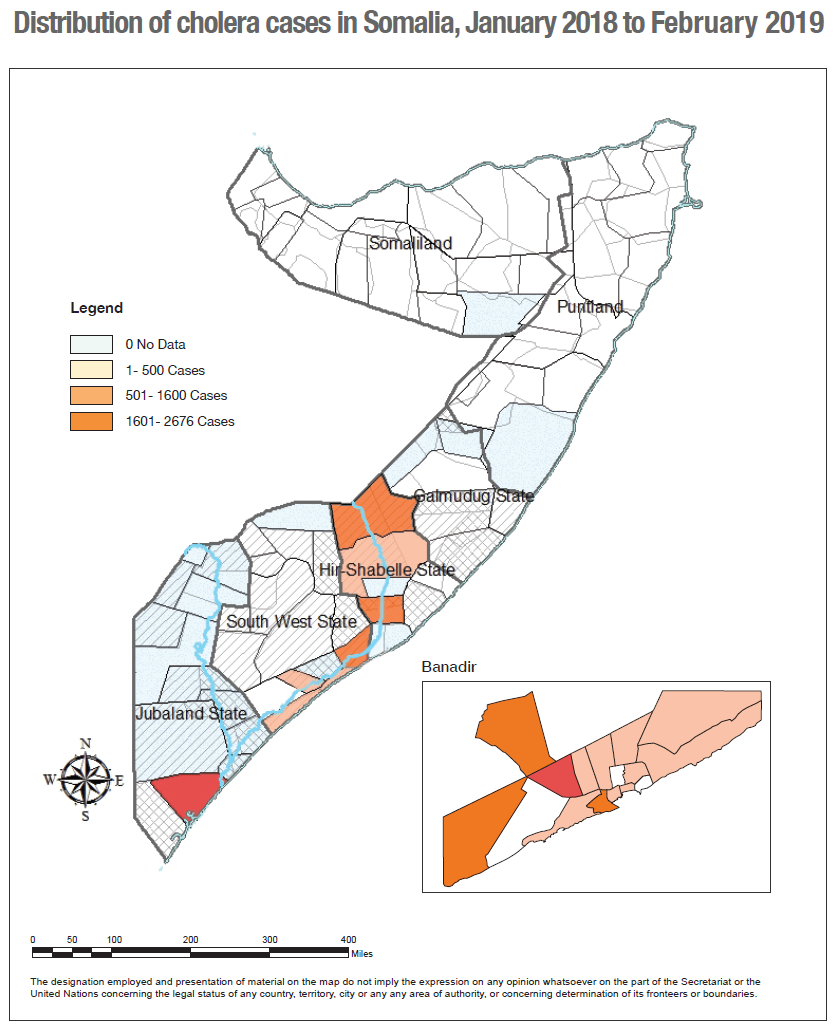

Fig. 1: Distribution of cholera cases in Somalia, January 2018 to February 2019 (source). With so many overwhelming challenges to address, where does one begin? For Somalia, fighting cholera has been one of the first priorities. Dr Lubogo: “If you’re looking for a disease that is both very deadly and at the same time easy to cure and prevent technically, cholera is it.” Since the current outbreak started in December 2017, Somalia has reported 6817 cases and 46 deaths. Although the outbreak is dwarfed by that in nearby Yemen, it is nevertheless a pressing cause for concern for WHO and health authorities, given also the vulnerable state of Somalia’s health system and population.

Fig. 1: Distribution of cholera cases in Somalia, January 2018 to February 2019 (source). With so many overwhelming challenges to address, where does one begin? For Somalia, fighting cholera has been one of the first priorities. Dr Lubogo: “If you’re looking for a disease that is both very deadly and at the same time easy to cure and prevent technically, cholera is it.” Since the current outbreak started in December 2017, Somalia has reported 6817 cases and 46 deaths. Although the outbreak is dwarfed by that in nearby Yemen, it is nevertheless a pressing cause for concern for WHO and health authorities, given also the vulnerable state of Somalia’s health system and population.

Although the structural and political causes of cholera outbreaks are often complex, on paper treatment and prevention are simple: both rely on access to safe water. Dr Lubogo: “Somalia has 13 million inhabitants, of whom an estimated 6 million are at risk of cholera, and 2 million at high risk. A large part of the high risk group are people living in refugee camps, and because camp locations keep shifting, setting up high quality, permanent water infrastructure with boreholes, protected sources, piped systems, becomes very complicated.”

A woman washes her hands outside the Cholera treatment centre in Banadir hospital in Mogadishu, Somalia. (Photo: Karel Prinsloo/Arete/Gavi)

A woman washes her hands outside the Cholera treatment centre in Banadir hospital in Mogadishu, Somalia. (Photo: Karel Prinsloo/Arete/Gavi)

But there is a plan. A global roadmap to ending cholera, launched last year. In it, WHO and its partners in the Global Taskforce on Cholera Control set the goal of reducing cholera deaths by 90% in the next 11 years, by improving surveillance, early warning, and oral cholera vaccination. As WHO’s Dr Dominique Legros said in a recent interview, “saying we can end cholera isn’t silly at all.”

Fig. 2: Multi-sectoral interventions to control cholera (source).

Fig. 2: Multi-sectoral interventions to control cholera (source).

An important part of that plan is the oral cholera vaccine,(OCV). OCV has more than proven its worth in Somalia: in 2017, 1.2 million Somalis aged 1 year and above received the vaccine, in different hotspot locations where year after year outbreaks of the deadly disease would occur. The result? Cholera cases fell by 75%, and all new cases currently reported are people that had not received the vaccine. The successful programme is now scaling up, targeting another 650,000 people during end of April of 2019.

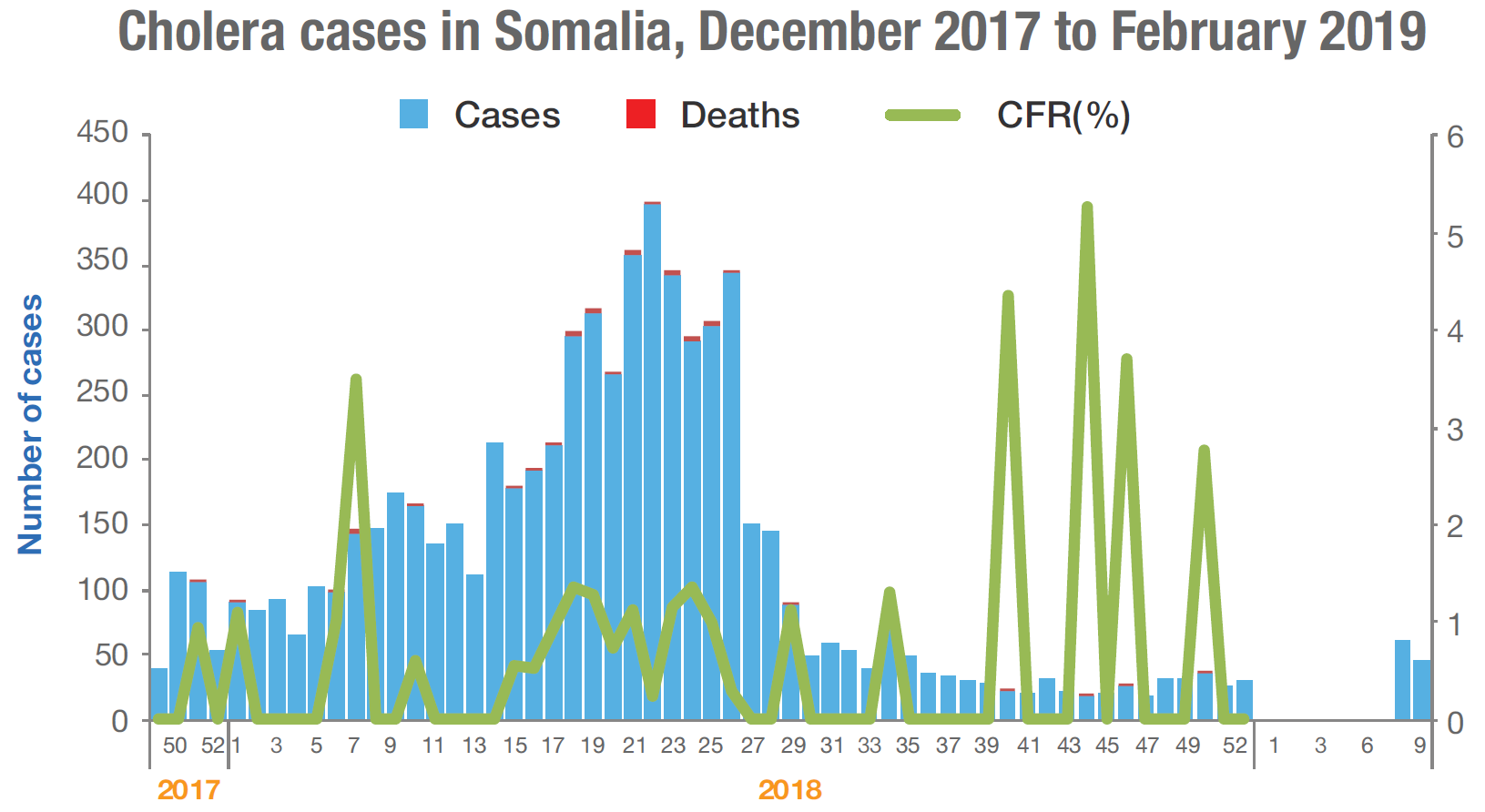

Fig. 3: Cholera cases in Somalia, December 2017 to February 2019 (source).

Fig. 3: Cholera cases in Somalia, December 2017 to February 2019 (source).

Despite its success, OCV isn’t a panacea. Instead, the vaccine’s three-year protection span provides a breathing space to implement other health programmes, as well as safe water and sanitation (WASH) measures. Somalia can again boast promising results in this regard; in all OCV campaigns, WHO has worked closely together with WASH partners, combining vaccination campaigns with health education and safe water interventions. As a result, 75% of the people in vaccinated areas now also enjoy improved access to safe water.

The next two years will be crucial to end the cholera outbreak in Somalia. Although the road ahead is not without obstacles, the success of the 2017 OCV campaign and the planned scale-up hold the promise of a cholera-free Somalia. If Dr Lubogo has his way, soon this deadly disease will be a specter of the past in all of Somalia.