An interview with Dr Dominique Legros, Cholera Team Lead at the World Health Organization.

There is a new battle plan in the fight against cholera. The document, aptly called “Ending Cholera”, exudes optimism and aims for a world in which the ancient disease is no longer a threat to public health. Dr Dominique Legros leads the efforts of the World Health Organization against cholera, and has been a part of this fight for 25 years. Technically, he says, fixing cholera is quite simple: it begins and ends with access to safe water. Reality, however, has proved considerably more complicated.

Yearly cholera burden: 47 countries, 2.9 million cases, 95 000 deaths

On the surface, cholera seems like a health problem. People ingest the bacterium Vibrio Cholerae, often in water severely contaminated with human feces; they get infected; and the subsequent symptoms of violent vomiting and diarrhea spread the bacteria and the disease further, sometimes explosively so. The health solutions are equally simple, cheap and available at first sight: boiling or chlorinating water, proper handwashing and bathroom use, and a vaccine that protects over half of those who receive it.

contaminated with human feces; they get infected; and the subsequent symptoms of violent vomiting and diarrhea spread the bacteria and the disease further, sometimes explosively so. The health solutions are equally simple, cheap and available at first sight: boiling or chlorinating water, proper handwashing and bathroom use, and a vaccine that protects over half of those who receive it.

"On the surface, cholera seems like a health problem. But in reality, it is primarily a political disease."

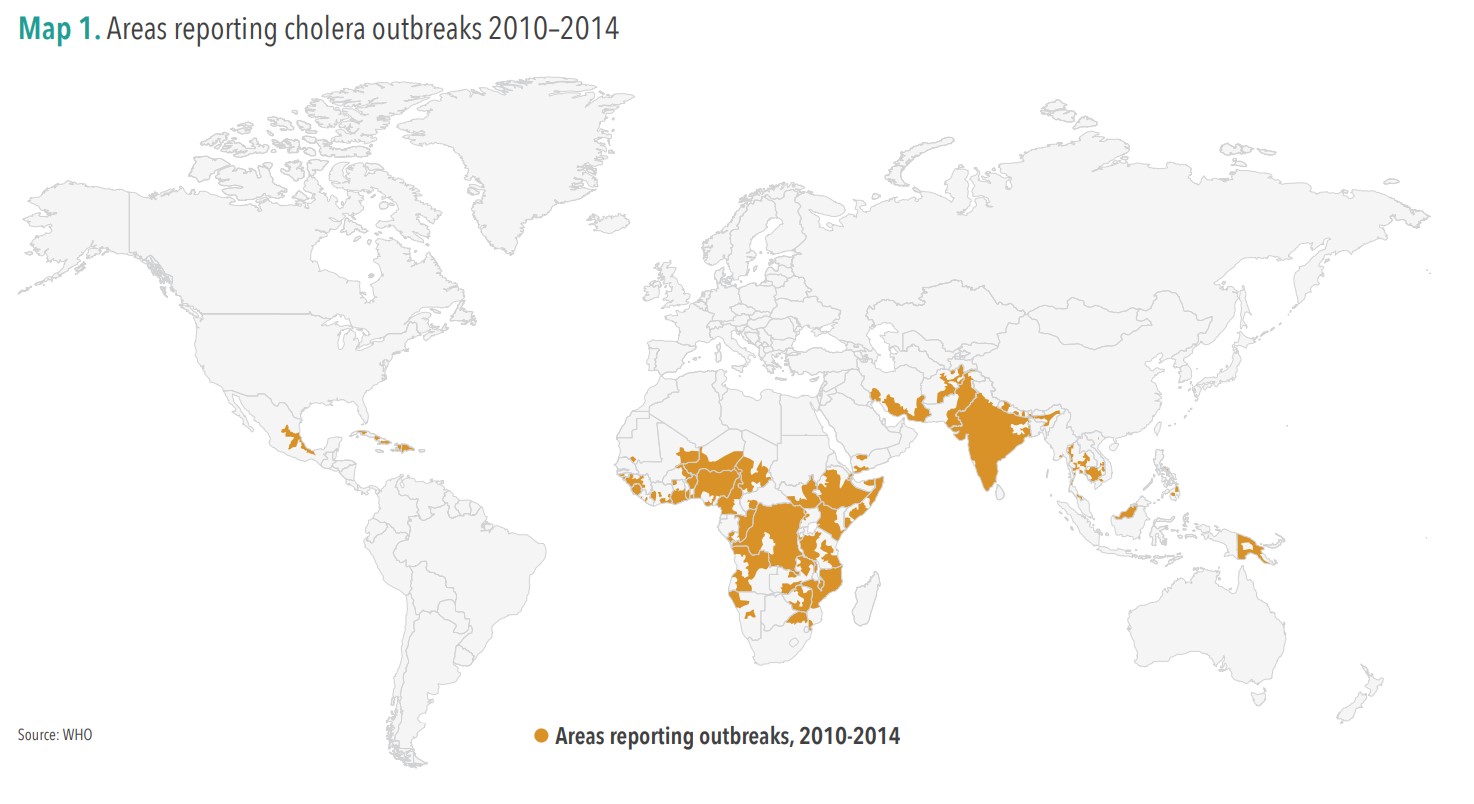

But the real reasons that make cholera so persistent are not related to health at all. First, a lack of safe water is what opens Pandora’s box of cholera time and again. This lack of safe water in turn is caused or worsened by natural disasters, climate change, armed conflict, and lack of infrastructure. Dr Legros: “Cholera is a disease of inequity: the map of cholera is pretty much the map of poverty. Health is only the visible part of this disease, the result that we see.”

Cholera, then, is primarily a political disease. In Dr Legros’ recent talk at TEDxGeneva, he explains how the people who suffer most are those who are disenfranchised, living in poverty, neglected by their governments in terms of access to clean water and infrastructure. “What we see in many cases are conflicting parties, each with control of separate areas, each accusing the other side of underinvesting in their people’s water and sanitation infrastructure. The same dynamic explains why some countries do not report their cholera cases. If you have a relatively stable country, but also a bad cholera situation, that is like saying ‘my governance is bad, I was not able to provide my own people with even basic services’.”

So why the optimism? Can we, as the hashtag says, #endcholera? Dr Legros sees a number of light points. Firstly, the coordinated approach of the Global Taskforce on Cholera Control (GTFCC). The GTFCC is a network of cholera experts from academia, government, nongovernmental organizations, United Nations agencies, and more, which drives the new cholera strategy. It includes health, but also water, sanitation, and all other relevant experts, which guarantees that cholera is seen as the political and multifaceted challenge it is.

"The effects of Oral Cholera Vaccine are spectacular. People say: wow, we can actually do something. It’s not some sort of lost cause."

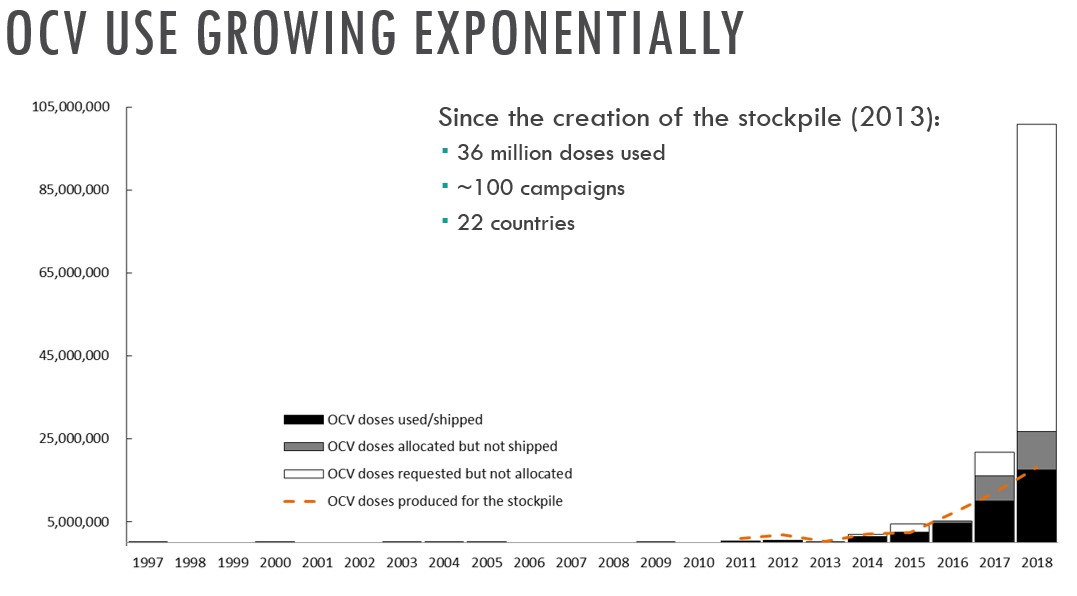

The second reason for optimism is the use of Oral Cholera Vaccine (OCV). In 2013, following consultations organized by the World Health Organization, a stockpile of vaccine was created for cholera outbreak control. The vaccine offers immediate protection to some 50-60% of those who receive it, protection which lasts for up to three years. This spectacular effect has also changed how people think of cholera. Dr Legros: “The Minister of Health in Somalia [which implemented an OCV mass campaign in 2017 with WHO support, red] told me: everybody is amazed, because we are vaccinating in an area where we know every year we have cholera, cholera, cholera. We vaccinate and poof! The treatment centers are empty. People say: wow, we can actually do something. It’s not some sort of lost cause.”

Strategic objective by 2030: 90% reduction of cholera deaths and elimination of transmission in up to 20 countries

Dr Legros feels that the impact of increased OCV use, coupled with a coordinated strategy to build solutions for safe water and sanitation, will usher in the resolution of long-standing political blockages: “We still have a number of countries that are at the stage of saying ‘no, we don’t have cholera.’ I’m willing to bet that within two to three years, this is going to change. They are already seeing the results in other countries, so they will have no other choice.”

Still, not all is won yet. South Asia remains a huge challenge to ending the disease, with its Bay of Bengal which is sometimes referred to as ‘the cradle of cholera’, for being the single origin of all cholera pandemics in history. Dr Legros: “Circulation and transmission in that region remains very high because of environmental factors, the size of the population, and because a country like India is not yet fully engaged. If we don’t engage everyone, we won’t control. And if we don’t control, we will see it spreading to other countries and regions.”

The outbreak was one of the worst ever seen, killing 20 000 people in a single month, among a million Rwandan refugees fleeing the genocide.

Dr Legros is all too familiar with the consequences of such uncontrolled spread. In 1994, he worked on cholera response in Goma (Democratic Republic of the Congo). The outbreak was one of the worst ever seen, killing 20 000 people in a single month, among a million Rwandan refugees fleeing the genocide. Dr Legros: “I saw families placing the bodies of their loved ones who had died from cholera alongside the road, for collection and mass burial, because the volcanic soil was too hard to dig a proper grave.”

Next month, the GFTCC is releasing an investment case, which according to Dr Legros will demonstrate that for every dollar invested, governments can save ten dollars that would otherwise go into cholera response. Add that to the thousands of lives saved, and suddenly political unwill doesn’t seem like such an insurmountable challenge. Dr Legros: “This is also why I spend my time communicating, doing advocacy. We can show that saying ‘we can end cholera’ is not silly at all.”

Stay tuned for the upcoming investment case and other work of Dr Dominique Legros and his colleagues, by following the GTFCC and the hashtag #endcholera on Twitter, as well as checking out WHO’s website on cholera.