23 December 2020 – Almost a year has passed since the COVID-19 pandemic started spreading across the world, putting millions of lives at risk, presenting unprecedented challenges on health systems, and further aggravating already weakened country economies. Health facilities are overwhelmed, and the health care workforce is facing global shortages in capacities, resources, and personal protective equipment, making them the most vulnerable group in the fight against this new threat.

Dr Ahmed Mady, pulmonology consultant at Cairo, Egypt’s Chest Hospital and director of the Health Isolation Hospital in Al-Ajami, who tragically died of COVID-19 in August. (Photo courtesy of Article19.ma)“While I'm lying on my bed in intensive care, I struggle to breathe. I suffer from a terrible pain that eats away at every part of my body, in which there is nothing left that is not connected to pipes and hoses. I watch the gazes of my fellow doctors and nurses, between fear and hope. And I see rapid and turbulent movements to equip the ventilator for a sharp drop of oxygen in my blood," said Dr Ahmed Madi, a pulmonology consultant at the Chest Hospital in Egypt, from his hospital bed after testing positive for COVID-19.

Dr Ahmed Mady, pulmonology consultant at Cairo, Egypt’s Chest Hospital and director of the Health Isolation Hospital in Al-Ajami, who tragically died of COVID-19 in August. (Photo courtesy of Article19.ma)“While I'm lying on my bed in intensive care, I struggle to breathe. I suffer from a terrible pain that eats away at every part of my body, in which there is nothing left that is not connected to pipes and hoses. I watch the gazes of my fellow doctors and nurses, between fear and hope. And I see rapid and turbulent movements to equip the ventilator for a sharp drop of oxygen in my blood," said Dr Ahmed Madi, a pulmonology consultant at the Chest Hospital in Egypt, from his hospital bed after testing positive for COVID-19.

"I know the failure of my respiratory system is the beginning of the road to my inevitable end – an end that I have seen before in others. I am the doctor responsible for treating this disease and I can clearly see its end now. All I hope for a speedy end to the moment of separation, and for God to protect my family and my children. I miss them so much,” he added.

Dr Madi died just days after delivering this message to his co-workers.

“Our hearts and thoughts are with the families of those who have lost loved ones. This is not just a loss for them, but a loss for the entire Region, where health staff working in some of the most complex settings in the world are acknowledged and valued for their dedication and commitment,” said Dr Richard Brennan, Director of Health Emergencies.

Compounded threats facing health workers in the Eastern Mediterranean Region

In the Eastern Mediterranean Region, where many health workers already face considerable risks, COVID-19 has added a new layer of complexity to the challenges they face. Beyond working in conflict zones and insecure settings, and being at risk of direct and indirect attacks, health workers are now exposed to an additional threat.

As countries in the Region continue to report increasing numbers of COVID-19 confirmed cases among their populations, the risks facing health workers are also on the rise.

“I wished desperately that COVID-19 wouldn’t reach Yemen, as we are already suffering from cholera, diphtheria, dengue, malaria and malnutrition, compounded with the ongoing conflict that has destroyed an already weak health system,” said Khalid Mohammed, a laboratory technician at the Central Laboratory in Sana’a. “Yes, I’m afraid for my health and my family’s, but if I can help, I will never stay aside. I’m working tirelessly 24 hours to run COVID-19 tests. This is the least I can do,” he added.

While health workers represent less than 3% of the population in most countries and less than 2% in almost all low- and middle-income countries, around 14% of COVID-19 cases reported to WHO are among health workers. In some countries, the proportion can be as high as 35%. Thousands of health workers infected with COVID-19 have lost their lives globally.

“Despite the challenges and risks, health care workers across the Region continue their work, putting the greater good first. They are an example to us all,” said Dr Brennan.

In Yemen, official numbers released by health authorities indicate that there are 407 infections among health care workers out of 2087 confirmed COVID-19 cases announced as 13 December 2020.

“COVID-19 has left Yemen and health care workers on the frontlines under severe pressure. We put our lives at risk to save the lives of our people. I have seen many doctors fall sick and be admitted on ventilators and monitors, or worse, die. This has been the hardest thing to witness,” said Sami Al Hajj, a young doctor working at the Science and Technology Hospital in Sana’a.

From 1 October to 15 December alone, Jordan reported the deaths of 23 doctors, the highest number since the start of the pandemic “We are all sad and in pain over the death of a constellation of heroes who stood as the first line of defence against the pandemic,” said Bisher Al-Khasawneh, Jordan’s Prime Minister, on social media.

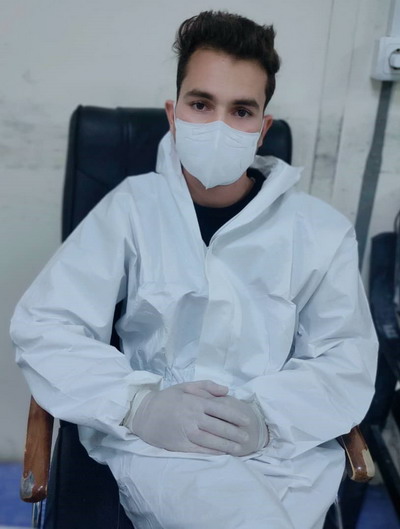

Azizullah Asghari, nurse at the ICU unit in Afghan Japan Hospital in Afghanistan, whose mother was infected with COVID-19 after he tested positive. Her death left him with a big loss“At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic no one was ready to work at the Afghan Japan Hospital which is designated for COVID-19 patients here in Kabul, because there were limited resources available to protect health workers, and the risk was very high,” said Mr Azizullah Asghari, an ICU nurse at Afghan Japan Hospital in Kabul, Afghanistan. “But the number of patients were increasing daily, so I decided to take the risk and started working as a nurse in the intensive care unit to help patients in severe or critical condition. Soon after, I became infected, and my family, including my mother, also tested positive. I lost my mother, who was only 42 years old with no underlying condition.”

Azizullah Asghari, nurse at the ICU unit in Afghan Japan Hospital in Afghanistan, whose mother was infected with COVID-19 after he tested positive. Her death left him with a big loss“At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic no one was ready to work at the Afghan Japan Hospital which is designated for COVID-19 patients here in Kabul, because there were limited resources available to protect health workers, and the risk was very high,” said Mr Azizullah Asghari, an ICU nurse at Afghan Japan Hospital in Kabul, Afghanistan. “But the number of patients were increasing daily, so I decided to take the risk and started working as a nurse in the intensive care unit to help patients in severe or critical condition. Soon after, I became infected, and my family, including my mother, also tested positive. I lost my mother, who was only 42 years old with no underlying condition.”

“I still cannot explain my mother’s death. I felt it with all my soul, there is no wound deeper than losing your loved ones like this. But I want to stand by people and try to save their loved ones. The commitment I made while graduating and the love I have for my people encouraged me to continue my work at the Afghan Japan Hospital and serve the patients with even more energy.”

Among the thousands of health workers in the regional polio programme who support the COVID-19 response, almost 256 polio staff have been infected, and three have lost their lives.

Making sure health care workers are protected physically and mentally

Health workers are at highest group at risk of infection due to frequent and close contact with suspected and confirmed COVID-19 patients. Global shortages of personal protective equipment have also made health workers soft targets, and those who have access to personal protective equipment may not be well trained enough to use them properly. Weak infection prevention and control measures in health facilities treating COVID-19 patients also increase their risk of exposure and infection.

While many health workers are infected in hospitals and health facilities, some are also infected due to exposure to the virus in community settings, including households.

But contracting COVID-19 is not the only risk that health workers face. With many frontline workers in close contact with infected patients, health workers are sometimes discriminated against as potential carriers of the disease and exposed to stigma and sometimes violence.

“I understand the fear of health care workers. It is a justified fear given the deteriorating health situation. But our people need us and our experience. I urge myself and fellow doctors to work this out together and support each other during this challenging time to survive the pandemic,” said Sami Al Hajj from the Science and Technology Hospital in Sana’a.

Exposed to levels of illness and death never seen before, some health workers are also at risk of psychological and emotional disturbances, illness and even death.

As the pandemic takes its toll on the mental health of health care workers. WHO and health partners are working hard to make sure that no one is left behind. Frontlines health workers are supported with mental health packages providing practical guidance and advice to help them cope up with the pressures faced.

Despite the global shortages in personal protective equipment, WHO and health partners have scaled up delivery. As of 15 December 2020, a total of 290 shipments of personal protective equipment kits have been shipped to 6 countries in Region from WHO’s regional logistics hub in Dubai, along with other medicines and equipment to support the COVID-19 response. Also, WHO and health partners have supported training health care workers across the region on infection, prevention and control guidance to reduce the risk of the virus spreading in health care settings. WHO also offers free courses on its Open WHO platform to train health workers on use of PPEs and other IPC measures properly.