H. Aounallah-Skhiri,1,2 H. Ben Romdhane,1 B. Maire,3 H. Elkhdim,4 S. Eymard-Duvernay,3 F. Delpeuch3 and N. Achour 1

الصحة والسلوكيات لدى الشباب في مدارس تونس في حقبة التحول الوبائي السريع

هاجر عون الله السخيري، حبيبة بن رمضان، برنار ماير، هدى الخديم، صابرينا إيمارد – دوفرني، فرنسيس ديلبيش، نور الدين عاشور

الخلاصـة: أجري الباحثون مسحاً مستعرضاً شمل عينة ممثلة تتألف من 699 من تلاميذ المدارس الثانوية، وكان الهدف من ذلك المسح تقييم سلوكيات الشباب في مدارس تونس وما يتعلق بها من جودة الحياة في الوسط الحضري التونسي. واتضح أن معدَّل فرط الوزن %20.7 وأن مستوى النشاط البدني لدى معظم الشبان غير كافٍ، وأنهم لم يألفوا القيام بأنشطة بدنية معتدلة بالتكرار الموصى به. وكانت الأحراز المستندة على المعايير والخاصة بالحالة النفسية قريبة من المعدَّل الوسطي، وكانت أفضل بقليل لدى الصبيان مما هي عليه لدى الصبايا. وترى الصبايا أنهن يرزحن تحت شدة ضغط نفسي تزيد عما لدى الصبيان. ومن بين جميع التلاميذ، أفصح %35 منهم أنهم يدخنون السجاير وأن %14 تعاطوا الكحول لمرة واحدة على الأقل أثناء حياتهم. وقد كان المصدر الرئيسي للتثقيف الصحي هو الإعلام (%59) والعاملين الطبيين (%36).

ABSTRACT To assess youth health behaviours and related quality of life in urban Tunisia, we conducted a cross-sectional survey of a representative sample of 699 secondary-school students. The overweight rate was 20.7%. Most of the sample had an insufficient level of physical activity and were unfamiliar with the recommended frequency of moderate physical activity. Norm-based scores of psychological state were about average, slightly better for boys than girls. Girls perceived themselves to be more stressed than boys. Of all students, 35% declared having smoked a cigarette and 14% having drunk alcohol at least once in their lives. The main sources of health education were mass media (59%) and medical staff (36%).

Santé et comportements des élèves tunisiens dans une période de transition épidémiologique rapide

RÉSUMÉ Afin d’évaluer les comportements des jeunes en matière de santé et la qualité de vie associée dans la Tunisie urbaine, nous avons réalisé une étude transversale à partir d’un échantillon représentatif de 699 élèves de l’enseignement secondaire. Le taux de surpoids était de 20,7 %. La plupart des jeunes avaient un taux d’activité physique insuffisant et ne savaient pas quelle était la fréquence recommandée d’une activité physique modérée. Les scores normalisés relatifs à l’état psychologique étaient proches de la moyenne et légèrement meilleurs pour les garçons que pour les filles. Les filles s’estimaient plus stressées que les garçons. Sur la totalité des élèves, 35 % ont déclaré avoir fumé une cigarette et 14 % avoir bu de l’alcool au moins une fois dans leur vie. Les principales sources d’éducation sanitaire étaient les médias (59 %) et le personnel médical (36 %).

1Institut National de la Santé Publique (INSP), Tunis, Tunisia (Correspondence to H. Aounallah-Skhiri:

2Doctoral School 393 ‘Public Health: Epidemiology and Biomedical Information Sciences’, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France.

3Research Unit 106, Research Institute for Development (IRD), Montpellier, France.

4Department of School Health, Ariana Governorate, Tunis, Tunisia.

Received: 24/01/07; accepted: 31/05/07

EMHJ, 2009, 15(5):1201-1214

Introduction

For many years, young people were considered a healthy group with no serious health problems compared to younger children. Nowadays, this population is exposed to many health risks mainly related to their lifestyles, but they do not yet have access to the protection associated with adulthood [1]. In industrialized countries, low levels of physical activity and unhealthy dietary practices contribute to significant and immediate health risks such as childhood overweight and obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus, as well as long-term health consequences such as cardiovascular disease, some cancers, overweight and obesity in adulthood, and adult-onset diabetes mellitus [2,3]. Behaviours and environmental factors also have an impact on health-related quality of life of youth [4,5].

Adolescent and youth health has progressively become a high priority concern in many industrialized countries [6–8], as it is acknowledged that an important share of adolescent morbidity can be attributed to preventable risk factors, e.g. sedentary lifestyles, poor eating behaviours, tobacco or substance use.

In developing countries in rapid epidemiological transition such as Tunisia, child and adolescent health is also becoming a real concern for decision-makers, and its assessment is viewed as a public health priority [9,10]. The globalization and westernization of lifestyles are probably the most important determinants of changes in health status in Tunisia nowadays [11,12], especially among urban adolescents.

The assessment and understanding of health behaviours is the first step in the design and implementation of services and preventive programmes. The aim of the current paper was to contribute to this assessment in the present Tunisian context.

Methods

Study design and participants

This was a cross-sectional questionnaire survey covering a representative sample of the third-level secondary-school classes in the Ariana area, a large neighbourhood of Tunis, covering a wide range of socioeconomic conditions. We used a 2-stage stratified random sampling frame. In the first stage, schools were stratified by district (n = 4) and 2 schools were selected from each district (except for 1 district where only 1 school was selected). In the second stage, we selected 4 third-level classes in each school, which yielded a total of 28 classes with a total of 753 students in the sample. The total population size of the third-level classes from which the sample was selected was 3539.

Owing to practical difficulties (school schedules, average length of time needed to administer the questionnaires, and the limits of self administration), the questionnaires were administrated separately to sub-samples of the students to optimize the rate of return, as indicated in pre-testing. The sample was divided into the following 3 sub-samples with all classes selected and allotted randomly:

- sub-sample A: 1 class per school answered the food behaviour questionnaire combined with the SF-36 scale, 61 males 102 females;

- sub-sample B: 1 class per school answered the health and lifestyle questionnaire, 53 males 123 females;

- sub-sample C: 2 classes per school answered the physical activity questionnaire, 140 males, 220 females.

For sub-sample C, our hypothesis was that the frequency of practising sport is low. Therefore to improve precision by reducing the dispersion of replies, we selected 2 classes rather than 1 as for the other sub-samples.

Physicians and nurses who are responsible for school health care were involved in asking classes of students to complete the questionnaire during a teaching session followed by anthropometric measurements (height and weight).

The study was approved by the health authorities in charge of the District of Ariana and by the school system authorities. Participation in the survey was voluntary and the participants were informed of the strict confidentiality of their answers.

Instruments

We used 4 questionnaires for data collection which were based on available questionnaires for self-reporting by adolescents. They were translated from the original French version into Tunisian Arabic dialect (with a back translation check). They were then pre-tested on different schoolchildren and adolescents before the beginning of the survey to ensure full understanding and feasibility.

Eating

Questions concerning knowledge, attitudes and behaviours were selected from standard published questionnaires [13,14] and adapted and tested for their pertinence to youth in Tunisia. We calculated the 3 following knowledge scores:

- definition of a healthy diet score, composed of 8 dichotomous questions (diet contains many fruits, many vegetables, little salt, a lot of red meat, a lot of fish, lack of fruit and vegetables, lack of red meat, rich in fat);

- definition of a well-balanced diet score, composed of 6 dichotomous questions (diversified nutrition: eat every food, eat reasonable quantities, eat 3 regular meals, avoid snacking between meals, avoid certain foods, e.g. fat, salt, favour certain foods, e.g. vegetables, fruit, dairy food);

- a nutrition risk factor score, composed of 3 dichotomous questions (nutrition plays: an important/moderate versus little/absent/don’t know role in cardiovascular diseases, obesity and diabetes). A score of 100 or 0 was attributed for each type of disease and the final score was the mean of the 3 scores.

Health-related quality of life

This was measured using the generic standardized SF-36 patient-assessed health survey [version 2 questionnaire, Quality Metric Inc., Lincoln, Rhode Island, United States of America (USA)] which is made up of 36 items assessing the following 8 health-related quality of life dimensions or scales: physical functioning; role-physical; bodily pain; general health; vitality; social functioning; role-emotional; and mental health. Scores were calculated using the SF health outcome scoring software, version 1.0. All scale scores range from 0 to 100, with 100 representing optimal physical functioning and well-being.

Physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain and general health are condensed in a physical component summary of health (PCS); social functioning, role-emotional, mental health and vitality contributed to the elaboration of the mental component summary (MCS) [15]. These 2 summary components have been extracted from the 8 original scales in order to reduce the number of outcome measures. Together, they account for 80%–85% of the variance in the 8 scales. These scores are standardized through norm-based scoring to a normal distribution with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation (SD) of 10 [16]. We used the general population in the USA for norm-based scores as it was the only set of data available for the software; it has been suggested that in international trials the original USA algorithms could be adopted as a reference [17].

Physical activity

This was assessed quantitatively using a frequency questionnaire that had previously been validated for Tunisian adults [18] concerning physical activity during the month preceding the survey, and adapted for youth by adding more-detailed questions about sport and leisure activities [19].

Health and lifestyle

This included youth health, health care consumption, knowledge about health in Tunisia and around the world, tobacco and alcohol consumption, attitudes about tobacco, drug and alcohol consumption, and perceived stress. Results for tobacco and alcohol consumption and perceived stress only are shown in this paper. Perceived stress used a validated stress scale composed of 4 questions enabling calculation of a Perceived Stress Scale Score [20]. Each question had 5 answers coded 0–100, or the reverse, depending on the sense of the question. Scores increased with a decrease in the level of perceived stress.

Weight was measured by trained health personnel using digital scales previously checked for accuracy (precision 100 g) and height was measured using standard wooden height gauges (precision 1 mm) with the participant in a standing position without shoes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as body weight/height2 (kg/m2). The international BMI cut-off points for children and adolescents developed by the Childhood Obesity Working Group of the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) were used to define normal weight, overweight or obese according to age and sex [21].

Young people with BMI values that corresponded to an adult BMI of ≤ 24.9 kg/m² were classified as normal weight, those with BMI values that corresponded to an adult BMI of 25.0–29.9 kg/m² were classified as overweight (pre-obese), and those with BMI values that corresponded to an adult BMI of ≥ 30.0 kg/m² were classified as obese.

Statistical analysis

We used SPSS, version 10.0 for data entry and validation and for statistical analyses. Values are expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Type 1 error risk was set at 0.05 for all analyses. We used the Student t-test and analysis of variance for comparisons of means and chi-squared for comparisons of percentages. Comparisons mainly concerned differences between males and females.

Results

Sample characteristics

Originally 753 subjects attending secondary schools were recruited into the study, but 20 were excluded because they were absent the day of the survey or returned an empty questionnaire; of the remaining 733, 34 did not enter their sex or birth date or refused to be weighed. The final sample therefore included 699 students (92.8%) aged 15–23 years among those attending 3rd grade of secondary school from February to April 2005 in the classes surveyed. Altogether, the sample included 254 males and 445 females; female:male ratio was 1.75.

The mean age of the participants in the total sample was 18.4 (SD 1.1) years. There were no major differences between sub-samples with respect to socioeconomic characteristics; significant differences between sexes concerning sociodemographic factors were observed only in sub-sample B where the parents’ level of education was significantly higher for boys (P < 0.01 for fathers’ education and P < 0.05 for mothers’) and mothers’ occupation category was also significantly higher for boys (P < 0.05), and in sub-sample C where boys were slightly older than girls [18.7 (SD 1.3) years versus 18.3 (SD 1.2) years, P < 0.01].

Overweight and obesity

The prevalence of overweight (including obesity) was 20.7%, and varied from 17.6% to 22.8% depending on the sub-sample. The prevalence of obesity was 4.7% in the total sample and varied from 2.5% to 5.8% depending on the sub-sample. The prevalence of obesity was significantly higher for males (7.1%) than for females (3.4%) (P < 0.05). The prevalence of overweight was not significantly related to socioeconomic status.

Food and nutrition

The mean scores for knowledge defining a healthy diet and a well-balanced diet were generally ≥ 70 (on a scale of 0 to 100) (Table 1). Two-thirds of the respondents considered that attention should be paid to what one eats from early childhood onwards, based on the parents’ role. The nutritional risk factor score (cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, obesity) was also high, > 70. The knowledge level score was generally higher for girls than boys, although a statistically significant difference was only found for knowledge of a well-balanced diet (P < 0.05).

However there was a difference in the perception of the quality of the participants’ own usual diet: the proportion of boys who considered they had a well-balanced diet was higher than that of girls; the majority of girls (60.4%) did not consider they had a well-balanced diet. The influence of health education was slightly greater for girls than boys but this was not statistically significant; between 20% and 25% were unable to estimate the degree of influence of health education. Almost 40% preferred street food, the proportion being higher among girls (43.6%) than boys (30.5%).

Most of the respondents (75.9%) said they watched television during meals with no significant difference between boys and girls (Table 1). Less than 10% reported sometimes skipping lunch. Girls reported skipping meals more frequently than boys, particularly breakfast (49.0% versus 25.4%, P < 0.01). About 50% reported snacking in the morning (45.6%) 2 to 7 days a week, or in the afternoon (59.4%). Snacking after dinner was mentioned by a smaller proportion (41.5%), almost twice as frequently by boys than girls (56.9% versus 32.7%, P < 0.01).

Physical activity

Only 13.9% considered that physical activity was necessary every day (Table 2). Slightly less than one-third said they practised a regular physical activity (based on their own perception), significantly more boys than girls (38.9% versus 24.8%, P < 0.01). In addition, the intensity of physical activity really undertaken was judged to be moderate by the majority (70.0%): high intensity was more frequently stated by boys (24.3%) than girls (9.3%). A very large majority considered practising daily moderate physical activity would be effective (93.0%) and pleasant (84.8%); only 28.5%, however, considered it easy to do, although more than 50% planned to do 30 min of moderate physical activity daily in the coming year.

Less than half of the subjects had physical education at school during the week preceding the survey (Table 3); the proportion was higher among girls than boys, but no significant difference was observed. A minority, 6.4% of boys and 15.9% of girls, said they did not like practising sport (P < 0.05), and 28.6% of girls and 13.6% of boys said they preferred watching others practising sport to practising themselves (P < 0.01). Around a quarter of the subjects said that sport was not a tradition in their neighbourhood, although the majority said they were encouraged to practise sport by their mothers (79.7%) and fathers (67.4%).

Apart from school physical education sessions, about 90% of the participants said they had done some sport during the week preceding the survey (Table 2), mainly walking (71.7%). Lack of time (68.3%), space (48.1%) and facilities (33.9%) were the main hindrances to practising sports.

Perception of quality of life

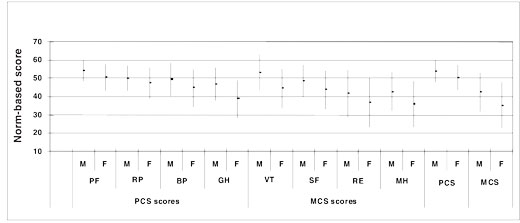

Figure 1 shows mean norm-based scores for the 8 scales and the 2 summary components of health-related quality of life. Norm-based scores were generally < 50 or close to 50. The mean score for MCS was lower than that for PCS for both girls and boys. Girls assessed their physical and mental health worse than boys for most of the components (P < 0.05), except for physical role, which was not statistically significant. Vitality (VT score) was significantly higher in the overweight group (51.2, SD 9.1 versus 46.9, SD 11.6; P < 0.05). There was no significant association with overweight in any score for boys, while there were significant differences for girls for VT score (P < 0.01) and for mental health and MCS scores (P < 0.05). More girls than boys also perceived themselves as being stressed: mean for perceived stress scores were 46.5 (SD 21.7) for girls and 60.5 (SD 16.5) for boys (P < 0.001) (Table 3).

Figure 1 Health-related quality of life according to sex showing mean (standard deviation) scores (M = males, F = females, PCS = physical component summary, MCS = mental component summary, PF = physical functioning, RP = role-physical, BP = bodily pain, GH = general health, VT = vitality, SF = social functioning, RE = role-emotional, MH = mental health)

Tobacco and alcohol consumption

About a third of respondents declared having smoked at least once in their life (Table 4). For shisha (traditional water pipe), the proportion was lower than for cigarettes but significantly higher for boys (25.6%) than for girls (4.8%) (P < 0.01). For smoking in general, 87.7% recognized that their parents were against it or would rather they did not smoke. More than 90% knew that smoking was considered to be a risk factor for certain diseases.

Significantly more boys (28.6%) than girls (7.1%) admitted having consumed alcohol at least once (P < 0.001), mainly from shops or the black market (Table 4). Most participants (87.3%) also recognized that their parents were against drinking or would prefer them not to drink.

Sources of health education

The main sources of health education were mass media (58.8%) and medical staff (35.6%) (Table 4). Although boys reported relying on mass media more frequently than girls, the difference was not significant.

Discussion

We found a high rate of youth overweight based on the IOTF definition, i.e. about 1 in 5 youth attending school. Comparison of our results with other studies should be done with caution because of the different classifications used to define overweight and obesity and population age. Our rate is close to the highest rate reported (overweight 25.4%; obesity 7.9%) in Europe in school-aged youth (10–16 years) in the 34 countries that took part in the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children study, in which a similar methodology was used [22].

Tunisia is now facing an epidemic of obesity linked to a rapid food and lifestyle transition similar to that observed in neighbouring countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region [23]. Food consumption patterns and dietary habits in this region have changed markedly during the past 4 decades. There has been an increase in per capita energy and fat intake in all countries, and changes in lifestyle and socioeconomic status in the region have had a significant effect on physical activity. Television advertising, long periods spent watching television and on the Internet, high intake of fast foods, and an increase in food intake outside the home have also been reported to be associated with obesity among children and adolescents in some countries in the region [23]. Significantly, a large percentage of both boys and girls in this survey reported regularly watching television whilst eating.

Young people attending school appeared to have sufficient knowledge about health. However, our results indicated a considerable gap between dietary knowledge and dietary behaviours, especially among girls (skipping meals, a preference for street food, and perception of not having a well-balanced diet). Our results are at odds with some observations reporting that girls tend to have a healthier diet than boys [24,25], as they are more likely to adopt prevention strategies for their health [26]. However this does not appear to be the rule [27,28]. It is recognized that knowledge about healthy food choices can be a predisposing factor for the adoption of a healthy diet but it is insufficient to motivate healthy eating; many other factors (e.g. psychosocial and demographic) also play a role [26,29]. Specific cultural factors can explain the widespread prevalence of overweight, particularly among married women, as female fatness has traditionally been viewed as a sign of social status and as a symbol of beauty and fertility [12,30]. However, another study in the region showed that the ideal body image of overweight and obese adolescents was significantly slimmer than their current body image, a clear sign of cultural transition [31].

Our study also showed that most of the young people at school had an insufficient level of physical activity. Less than half practised weekly physical activity at school although up to 79% declared having practised sport some time during the week preceding the survey. While they were largely unaware of the recommended frequency of daily moderate physical activity, the young people expressed willingness and a consciousness of the benefits of practising regular physical activity. Most of the young people in our study considered that practising sport is pleasant, but cited a number of hindrances. An insufficient level of sport was observed more than 10 years ago in 1993 during a nation-wide study in Tunisia [10]: only 49.3% of youth (17–24 years) who lived in the Tunis region (including the Ariana neighbourhood) declared they practised a sport.

Using the SF36 instrument, self-ratings of general health are among the most commonly used measures of health status. They are thought to be good predictors of mortality, irrespective of the method of measurement. Even though it is mostly employed with adults, the instrument is also adapted for use with young people [32].

We found a significant association between some health-related quality of life scores and overweight for girls, but not for boys. Such an association was recently described for Australian children, weak for overweight, and more marked for obesity [33]. Pinhas-Hamiel et al. found a statistically significant relationship between BMI and general and physical health but not psychosocial outcomes [34]. This indicates that girls worry more about overweight than boys in the Tunisian school population; in boys, it may express the absence of physical impairment linked to the low level of obesity; or alternatively, a lower level of consciousness, or a better social acceptance of moderate overweight. Boys rated better than girls for each separate and synthetic score. Girls also reported a more frequent perception of not having a well-balanced diet or being more stressed on average than boys. This is in agreement with studies that explored the psychological status of youth [35,36]. While children report a very good quality of life, which is largely independent of gender, adolescents have a lower health-related quality of life score; and a larger decrease was found for females than males [37]. Stress appears more frequently in females, although it does not seem to play a significant role in differences in health [38,39]. Gender disparities, not unique to Tunisian youth, could be related to many factors such as disparities in the level of physical activity, the importance of body image, health considerations and social discrimination.

Overall, tobacco smoking among youth is less pronounced in Tunisia than in more-industrialized countries. In the USA 58% of people aged 10–24 years had smoked at least once [40], and this was also the case for 70% of 14–20 year-old students in Spain [41], while in our study only 35% of young people aged 15–23 attending school had already smoked. This is consistent with the conclusion of a recent world review of global tobacco use in 13–15-year-olds attending school which showed that, on the whole, Eastern Mediterranean Region youth are currently less exposed to cigarette use than young Europeans and Americans [42] although the use of other tobacco products like the water-pipe is gaining popularity among boys.

About 75% of youth in the USA and 85% in Spain had tried alcohol [40,41], while in Tunisia only 29% of males and 7% of females had done so. Similar results were reported in other studies in Arab countries [43,44] with significantly lower levels of addiction, specifically among females.

This study provides new and recent information on health status and various health perceptions or behaviours of youth at school in an actively urbanizing area of the capital of Tunisia. Its main strength is to present gender differences in perceived health-related quality of life, which had not been investigated previously in this young population. There are clear limitations due to the difficulty Tunisian youth have accepting long interviews or self-administered questionnaires on their personal behaviours during school hours, which led us to distribute the different questionnaires to different groups. The use of smaller sub-groups may have contributed to a loss of power in stratified analyses and precluded cross analyses between main themes. However, it ensured very high return and completion rates and probably fewer biases in the answers. Anonymous written self-reports in the form of questionnaires filled out at school also avoided any direct influence by other members of the family.

In conclusion, our study suggests the need to implement a relevant strategy for health promotion among children and youth as part of a national programme to prevent diet-related chronic diseases. This should be gender sensitive as the magnitude of the problems is different for both males and females.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the students who agreed to take part in this study, to the staff of physicians and nurses in school medicine in Ariana, and to the teaching and administrative staff of the schools surveyed, who helped us to undertake the study.

References

- Nutrition in adolescence—issues and challenges for the health sector. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2005 (WHO discussion papers on adolescence, issues in adolescent health and development).

- Daniels SR et al. Overweight in children and adolescents: pathophysiology, consequences, prevention, and treatment. Circulation, 2005, 111:1999–2012.

- Must A, Strauss RS. Risks and consequences of childhood and adolescent obesity. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders, 1999, 23:S2–11.

- Topolski TD et al. Quality of life and health-risk behaviours among adolescents. Journal of adolescent health, 2001, 29:426–35.

- Gerhardt CA et al. Stability and predictors of health-related quality of life of inner-city girls. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics, 2003, 24:456–8.

- Steptoe A et al. Trends in smoking, diet, physical exercise, and attitudes toward health in European university students from 13 countries, 1990–2000. Preventive medicine, 2002, 35:97–104.

- Payne D et al. Adolescent medicine in paediatric practice. Archive of disease in childhood, 2005, 90:1133–7.

- Rigby MJ et al. Child health indicators for Europe: a priority for a caring society. European journal of public health, 2003, 13(3 Suppl.):38–46.

- Ghannem H, Fredj AH. Transition épidémiologique et facteurs de risque cardiovasculaire en Tunisie [Epidemiological transition and cardiovascular risk factors in Tunisia]. Revue épidémiologie et santé publique, 1997, 45:286–92.

- Les jeunes au quotidien. Environnement socio-culturel et comportement de santé. Tunis, Office National de la Famille et de la Population, 1996.

- Ghannem H. The challenge of preventing cardiovascular disease in Tunisia. Preventing chronic disease, 2006, 3(1):A13.

- Mokhtar N et al. Diet culture and obesity in Northern Africa. Journal of nutrition, 2001, 131:887S–92S.

- Pettinger C, Holdsworth M, Gerber M. Psycho-social influences on food choice in Southern France and Central England. Appetite, 2004, 42:307–16.

- El Ati J et al. Food frequency questionnaire for Tunisian dietary intakes: development, reproducibility and validity. Arab journal of food and nutrition, 2004, 5:10–30.

- Larsson U, Karlsson J, Sullivan M. Impact of overweight and obesity on health-related quality of life—a Swedish population study. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders, 2002, 26:417–24.

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SK. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: a user’s manual. Boston, Massachusetts, The Health Institute, 1994.

- Jenkinson C. Comparison of UK and US methods for weighting and scoring the SF-36 summary measures. Journal of public health medicine, 1999, 21:372–6.

- El Ati J et al. Development, reproducibility and validity of a physical activity frequency questionnaire in North Africa. Arab journal of food and nutrition, 2004, 5:148–67.

- Nolin B et al. Enquête québécoise sur l’activité physique et la santé 1998 [Quebec survey on exercise and health]. Québec, Institut de la Statistique du Québec, Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec et KinoQuébec, 2002.

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of health and social behavior, 1983, 24:385–96.

- Cole TJ et al. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. British medical journal, 2000, 320:1240–3.

- Janssen I et al. Comparison of overweight and obesity prevalence in school-aged youth from 34 countries and their relationships with physical activity and dietary patterns. Obesity review, 2005, 6:123–32.

- Musaiger AO. Overweight and obesity in the Eastern Mediterranean region: can we control it? Eastern Mediterranean health journal, 2004, 10:789–93.

- Doumont D, Libion F. Santé des familles : influences du mode de vie. 1ère partie (alimentation, alcoolisme et tabagisme) [Health of families: influence of lifestyle. Part 1 (diet, alcohol use and smoking)]. UCL-RESO, Unité d’Education pour la Santé. Louvain, Belgique : Université Catholique, Ecole de Santé publique, 2003.

- Anderson AS, Macintyre S, West P. Dietary patterns among adolescents in the west of Scotland. British journal of nutrition, 1994, 71:111–22.

- Gracey D et al. Nutritional knowledge, beliefs and behaviours in teenage school students. Health education research, 1996, 11:187–204.

- Sjoberg A et al. Meal pattern, food choice, nutrient intake and lifestyle factors in the Goteborg adolescence study. European journal of clinical nutrition, 2003, 57:1569–78.

- Samuelson G. Dietary habits and nutritional status in adolescents over Europe. An overview of current studies in the Nordic countries. European journal of clinical nutrition, 2000, 54(Suppl. 1.):S21–8.

- Sweeting H, Anderson A, West P. Socio-demographic correlates of dietary habits in mid to late adolescence. European journal of clinical nutrition, 1994, 48:736–48.

- Mehio-Sibai A et al. Ethnic differences in weight loss behaviour among secondary school students in Beirut: the role of weight perception. Sozial- und Praventivmedizin, 2003, 48:234–41.

- Al-Sendi AM, Shetty P, Musaiger AO. Body weight perception among Bahraini adolescents. Child: care, health and development, 2004, 30:369–76.

- Brazier JE et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. British medical journal, 1992, 305(6846):160–4.

- Williams J et al. Health-related quality of life of overweight and obese children. Journal of the American Medical Association, 2005, 293:70–6.

- Pinhas-Hamiel O et al. Health-related quality of life among children and adolescents: association with obesity. International journal of obesity, 2006, 30:267–72.

- Bener A, Tewfik I. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and associated psychological problems in Qatari's female population. Obesity reviews, 2006, 7(2):139–45.

- Viner RM et al. Body mass, weight control behaviours, weight perception and emotional well being in a multiethnic sample of early adolescents. International journal of obesity, 2006, 30(10):1514–21.

- Bisegger C et al. Health-related quality of life: gender differences in childhood and adolescence. Sozial- und Praventivmedizin, 2005, 50:281–91.

- Bothmer MIK von, Fridlund B. Gender differences in health habits and in motivation for a healthy lifestyle among Swedish university students. Nursing and health sciences, 2005, 7:107–18.

- McDonough P, Walter V. Gender and health: reassessing patterns and explanations. Social science & medicine, 2001, 52:547–59.

- Grunbaum JA et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2003. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 2004, 53 (SS–2):1–96.

- Hidalgo I, Garrido G, Hernandez M. Health status and risk behaviour of adolescents in the north of Madrid, Spain. Journal of adolescent health, 2000, 27:351–60.

- Warren CW et al. Patterns of tobacco use in young people and implications for future chronic disease burden in adults. Lancet, 2006, 367:749–53.

- Al-Haddad N, Hamadeh RR. Smoking among secondary-school boys in Bahrain: prevalence and risk factors. Eastern Mediterranean health journal, 2003, 9(1/2):78–86.

- Refaat A. Practice and awareness of health risk behaviour among Egyptian university students. Eastern Mediterranean health journal, 2004, 10(1/2):72–81.