M. Letaief,1A. Ben Hmida,2 B. Mouloud,3 B. Essabbeh,3 R. Ben Aissa2 and N. Gueddana2

تنفيذ برنامج تحسين الجودة في مركز تنظيم الأسرة والصحة الإنجابية في الموناستير، تونس

منذر اللطيف، عبد المجيد بن حميدة، بسمة مولود، بشرى الصباح، ريم بن عيسى، نبيهة قدانة

الخلاصـة: استهدفت الدراسة تحسين جودة خدمات تنظيم الأسرة والصحة الإنجابية في أحد مراكز تنظيم الأسرة من خلال تنفيذ برنامج لتحسين الجودة. وأجري مسح لدى المستفيدين من خدمات المركز للتعرف على المشكلات المتعلقة بالجودة، ثم قام فرقاء الرعاية الصحية بتحليل أسباب المشكلات واستنباط الحلول لثلاث مشكلات منتقاة وبإعداد إطار لضمان الجودة. وقد تمثَّلت المشكلات المنتقاة في فتـرة الانتظار الطويلة في المركز، وقصور التكامل بين خدمات تنظيم الأسرة والصحة الإنجابية، والافتقار إلى أسلوب شمولي. وكان هدف المرحلة النهائية هو اختبار وتنفيذ إجراءات تصحيحية.

ABSTRACT: We aimed to improve the quality of family planning and reproductive health services in a family planning centre though implementation of a quality improvement programme. Clients were surveyed to identify quality-related problems. Health care teams then analysed the causes of the problems, developed solutions for 3 selected ones and established a quality assurance framework. The selected issues were: long waiting time at the centre; insufficient integration of family planning and reproductive health services; and lack of a holistic approach. The final phase was aimed at testing and implementing corrective measures.

Mise en place d’un programme d’amélioration de la qualité dans un centre de planification familiale à Monastir (Tunisie)

RÉSUMÉ: Notre objectif était d’améliorer la qualité des services de planification familiale et de santé génésique dans un centre de planification familiale grâce à la mise en place d’un programme d’amélioration de la qualité. Une enquête a été menée auprès des utilisateurs et utilisatrices afin de recenser les problèmes relatifs à la qualité. Les équipes de soins ont ensuite analysé les causes des problèmes, élaboré des solutions pour répondre à trois problèmes particuliers et mis en place un cadre d’assurance de la qualité. Les problèmes retenus étaient: la longueur du temps d’attente au centre; le regroupement insuffisant des services de planification familiale et de santé génésique ; et l’absence de démarche globale. La phase finale visait à tester puis appliquer des mesures correctives.

1Preventive Medicine and Epidemiology Unit, University Hospital of Monastir, Monastir, Tunisia ( Correspondence to M. Letaief:

2Family Planning National Board, Tunis, Tunisia.

3Family Planning and Reproductive Health Centre of Monastir, Monastir, Tunisia.

Received: 24/10/05; accepted: 23/02/06

EMHJ, 2008, 14(3):615-627

Introduction

Promoting family planning and sexual health have been a priority in Tunisia for 40 years. Indeed, a family planning programme has been in place since 1966 and has been revised to include the broader definition of sexual and reproductive health according to the United Nations (UN) International Conference on Population and Development in Cairo 1994 [1].

To some extent important milestones have been achieved and this has been shown by the sexual and reproductive health indicators, i.e. prevalence of contraceptive use over 65%, synthetic fertility index of 2.00, birth rate of 17‰ [2].

Over the next decades, challenges facing health care systems and facilities will be related to health care quality. Thus, improving the delivery and the quality of reproductive health services is becoming crucial to address reproductive health problems and to enhance effective use and management of such facilities [3].

Client satisfaction, defined as the degree of discrepancy between expectations and perceived performance [4], represents an important indicator of perceived quality of services, and obviously would allow more efficient use of health care and reproductive health facilities [5,6].

Quality improvement refers to the use of appropriate methodologies to narrow the gap between the current and expected levels of quality; it uses quality management tools and principles to understand and address system deficiencies.

Quality improvement activities are conducted using variations on a 4-step method: identify (determine what to improve), analyse (understand the problem), develop hypotheses (determine what change(s) can improve the problem) and finally test and implement, or Plan Do Study and Act (PDSA) [7].

Despite the important emphasis on improving the quality of reproductive health services, client satisfaction surveys and quality improvement programmes are infrequent in Tunisia. Our study is a pilot quality-operation study [8] which aimed at improving the quality of family and reproductive health services in a family planning centre. This paper presents the design and implementation of the programme.

Methods

We carried out a 4-phase quality operation study. The phases were: identifying the problems (client satisfaction survey), analysing the causes of problems and developing solutions for the selected ones (quality methods and tools), establishing a quality assurance framework, and testing and implementing corrective measures.

First phase: evaluation of the clients’ perceived quality

The first stage was a client satisfaction survey which was performed in order to assess the current level of care provided by the services in relation to the expectations and preferences of the clients.

We carried out a descriptive study of 215 women attending Monastir family planning centre from March to June 2004 for reproductive health services. The women were selected by systematic random sampling (every fourth woman attending during the study period). The study tool was a questionnaire (exit interview) which was developed by a multidisciplinary committee (2 epidemiologists, 2 family planning centre managers, 1 gynaecologist, 1 psychologist and 3 general practitioners). It was developed in Tunisian Arabic dialect and oriented towards sexual and reproductive health services. Our conceptual framework for evaluation of the services was based on the following elements: accessibility and availability of the services; availability of basic equipment and essential facilities; information supplied by the practitioners to the clients; choice of contraceptive methods available at the centre; perceived technical services provided; relationship between health care professionals and client; continuity of services; provision of a holistic approach (e.g. social, psychological concerns addressed); and integration of preventive care, e.g. cervical screening, screening and early detection of breast cancer and treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

The final version of the questionnaire required the response to 31 items related to reproductive health client satisfaction using an ordinal Likert scale. Some additional user information (age, level of education, occupation, socioeconomic status, gynaecological and obstetric history) were also noted. The questionnaire was filled in by external interviewers using a structured approach. The clients were clearly informed about the objectives and the procedure of the study. Their participation was voluntary and they were free to withdraw without any negative consequences, with respect to information privacy and confidentiality. If a client refused to participate then we invited the next client at the exit point. A pre-test period was carried out on a sample of 30 clients to test the feasibility of the study and to assess the validity of the questionnaire so as to prevent future operational problems.

Data were coded and entered using SPSS, version 11. Data analysis was performed by using descriptive parameters [mean, median, standard deviation (SD) quartiles, percentages] according to variable categories (quantitative or qualitative) and distribution. Priorities were listed using relative frequency (%) of gaps perceived by the clients in the reproductive health services provided.

Second phase: analysing the problem causes and developing solutions

To achieve this objective, we organized 3 seminars aimed at training the local team about quality improvement methods and tools. Brainstorming is a way for a group to generate as many ideas as possible and requires participants to be willing to express their ideas without evaluating them. This was used both for listing the possible causes and developing solutions to a specific problem. Solutions were selected using a simple rating scale. Setting the priority of problems was done by multivoting and weighted voting methods.

Third phase: establishing a quality assurance framework

Different elements of the quality assurance framework were developed by the local team, following their training on the quality improvement methods and tools.

The survey results were shown and discussed by the team. Quality-related problems were then prioritized according to their relative frequency of perceived inappropriateness according to the clients’ preferences and expectations.

The quality assurance framework starts with the quality-related problem to be addressed by the quality assurance programme, e.g. long waiting time at the centre. Then, the problem is quantified by reference to the client satisfaction survey results (% of clients perceiving long waiting time). The reasons for considering the problem as a priority are explained (frequent health service problem, organizational problem, team-based problem, health behaviour related problem, etc.). The framework also includes the programme objective, the activities to be carried out, the person(s) responsible, the indicator(s) to measure the activity and the source(s) of verification, and the indicator standard (norm) to be achieved.

Fourth phase: testing and implementing corrective measures

With reference to the PDSA cycle, the following steps were carried out:

Make a plan of action of the test and verify that all the persons involved in the solution understand the change.

Document modifications made by the intervention or the solution.

Verify that the intervention was tested according to the original plan and compared observed results with desired results

Take appropriate action based on the results of the study to see whether to maintain, develop another solution or correct and adapt the proposed solution.

Results

Study sample general characteristics

All the 215 randomly selected clients accepted to voluntarily participate in the study. The mean age of the study sample was 32 (SD 7) years (minimum 20 years, maximum 48 years). Urban residents of Monastir constituted 94% of the study sample and 45% had completed primary school education. The majority of the clients were married (91.1%); only 7.5% were single. They had a median of 3 children (minimum 0, maximum 7, interquartile range 2 children). They had a median number of previous pregnancies of 4 and a median number of previous induced abortions of 1. As regards attendance, 45% of the clients attended the clinic for unwanted pregnancies, 5% for a control visit after an induced abortion, 20% for contraception, 17% for prenatal visits, 8% for information about STI prevention and 5% for other preventive issues.

Evaluation of the perceived quality of reproductive health and family planning services

We used an ordinal Likert scale in the questionnaire to evaluate the quality of the services as perceived by the clients. Table 1 shows the frequency of the issues that were rated as unsatisfactory by the clients.

Team-selected problems for improvement

The results were presented to the team and after discussion and using a multi-voting method, they came up with a list of issues to be addressed by the quality assurance programme (Table 2).

During the next sessions, the team selected 3 problems that would be addressed in a quality assurance framework. Their selection was based on the importance of the problem, its feasibility, it requiring a team-dependent solution and the potential for improvement. The 3 problems were: the perceived long waiting time, the lack of integrated services and lack of a holistic approach.

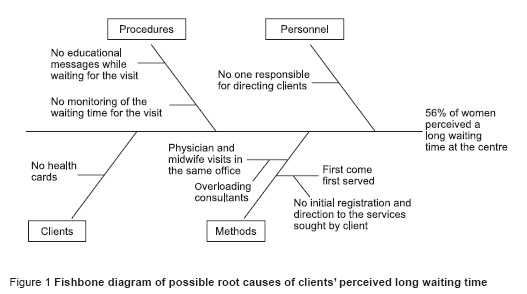

Perceived long waiting time

Through discussion, the team devised a fishbone diagram of the possible causes of the problem (Figure 1). Afterwards, they were invited to develop a specific quality assurance framework to address the issue of waiting time (Table 3). The objective was to reduce the waiting time inside the clinic. A set of activities were developed and implemented. They were assessed by noting the length of time between registration at the reception desk and seeing the doctor. After 1 month, the evaluation of this indicator using the lot quality assurance sampling (LQAS) method on a small sample of records will indicate whether the activities implemented should be maintained, corrected or replaced by other solutions (PDSA cycle).

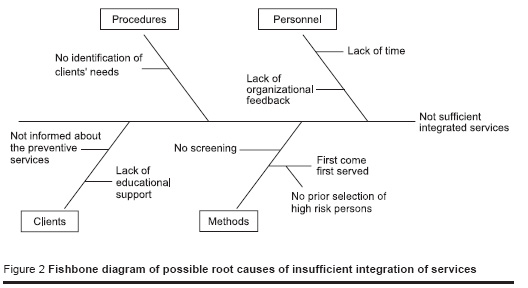

Lack of integrated services

In a similar way, the possible causes for a lack of integrated services were listed and presented in a fishbone diagram (Figure 2). The objective was to improve the proportion of integrated preventive services. Activities were related to providing information, education and communication for the clients about preventive measures. Health professionals were invited to note on the medical records the occurrence of cervical screening and breast self-examination training (Table 4).

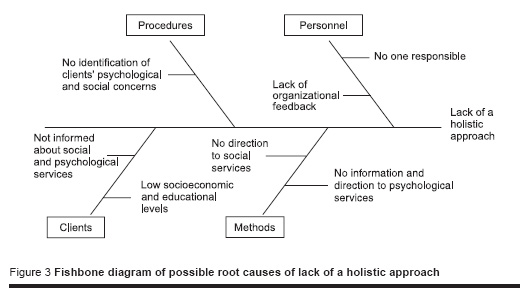

Lack of a holistic approach

Social and psychological concerns are important issues according to the clients’ preferences and expectations. The summary of the possible causes of this shortcoming is shown in Figure 3. The objective was to improve the awareness of health-care professionals about the clients’ social and psychological concerns. The quality assurance framework is shown in Table 5.

Discussion

In the first phase, the study showed a list of problems related to the clients perceived quality of reproductive health and family planning services. These concerns were then included in a quality improvement intervention. We used quality assurance methods and principles to construct a quality assurance framework that was implemented in the Family Planning and Reproductive Health Centre of Monastir.

The success of our experience will be valuable for the local team. It will constitute an important incentive for sustaining the quality improvement experience. Similar teams in other such centres could be motivated to start a similar approach. Thus a constructive and positive view of the quality assessment will be shared among these facilities.

In the field implementation of the study, we noted that in the pre-test phase most of the clients interviewed gave biased responses, i.e. saying that services were very good and appropriate. This bias is often encountered in this type of survey and was corrected by underscoring the importance of presenting and explaining the study objectives to the clients.

Health care quality assessment generally uses 2 approaches, either from the “technocrat” perspective of the health care professionals or from the lay perspective of the clients [9].

With the first approach, the technocrat perspective, the services are classified as good when they are in accordance with the standards and norms defined by health professionals. In the second approach, the clients play an important role in defining and assessing the quality of care [10–12].

Despite its benefits, measuring client satisfaction has been criticized for representing both a measure of care and a reflection of the respondent. To overcome this problem, some organizations prefer measuring clients’ perceptions instead. For example, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations has replaced the term “satisfaction” with the term “perception of service” [13]. Then the client’s perceived quality is a subjective dynamic perception of the extent to which expected health care is received [14].

The client satisfaction assessment could represent a part of a multidimensional approach for conducting a quality improvement intervention. This is particularly used in the client-oriented provider efficient (COPE) method, which is a process and set of tools designed to help health-care staff at a service delivery site to continuously assess and improve their services [15]. It is built on a framework of client rights and staff needs. The method encourages staff to review the way they perform their daily tasks and serves as a catalyst for analysing the problems they identify [16].

In our study there was a list of quality-related problems. They were mainly related to the integration of reproductive health and family planing services. For example, over 90% of the clients reported that they were not informed about cervical cancer prevention. Clients also did not receive clear information about the prevention of the STIs (87%) and breast cancer (72%). These results are in accordance with those published by other authors, reporting that in most cases, clients only received services for which they presented at the health facility [17]. These results underscore the need for implementing integrated reproductive health and family planing services. In practice this requires changing the attitudes and approaches of providers from a paternalistic to client-centred one [3,18].

According to our clients’ perceptions, there was a need to improve the communication and interaction between health-care professionals and clients. For example, doctors frequently do not introduce themselves before examination (87%), health professionals do not attend to the psychological and social concerns of the clients (83%), doctors are not interested in the patients’ health problems (66%). The issue of improving the communication and interaction should be considered a priority in the quality assurance framework, promoting the implementation of a holistic and comprehensive approach.

The results also highlighted the need to improve the perceived quality regarding the service provision for clients attending the clinic for induced abortion. Further actions are required to standardize the technical process of care to tackle inappropriate variations [19].

A database was created which included some indicators that could be used for future assessment of service performance. The database also helps health professionals to file the medical records. The data will also be used to monitor and assess the success of the different activities of the 3 quality frameworks implemented. The local team was asked to develop an indicator for each activity, its source of control and operational standard. The latter was developed according to the field features. For the monitoring of the quality indicators the LQAS method was used. This was developed to meet industrial quality control needs and has been applied to health surveys. Lot sampling is a simple and efficient procedure for quality assurance and WHO has used this method to assess immunization coverage [20].

Finally, to improve the performance and quality of reproductive health and family planning services, we recommend the following strategies.

Widen the experiences of quality improvement interventions to the other family planning and reproductive health clinics. The point is to build the capacity of healthcare teams to use appropriate quality improvement tools and methods. This requires the creation of a core group of quality improvement experts whose mission is to help and coach teams willing to start quality improvement initiatives.

Encourage teams and clinics to begin quality improvement exercises, with the attention being given to create incentive measures (certification, accreditation).

Promote benchmarking, i.e. the use of information and the development of indicators that could be used to implement a culture of quality and to share experiences among similar health facilities.

Complete the approach of quality assessment by the evaluation of the performance of healthcare professionals and develop and use protocols that are evidence-based, for the spectrum of reproductive and family planning services.

Promote communication and interaction between healthcare professionals and clients. This point can be done by adopting a client-centred approach.

Promote the integration of preventive care by targeting interventions according to clients’ needs rather than vertical programmes.

Develop and promote future research about the economic evaluation of reproductive health interventions, which will raise the awareness of health professionals about the cost of interventions and enhance the efficient use of reproductive health services [ 21 ].

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of the World Health Organization Regional Office for the East Mediterranean (Research Policy and Cooperation Unit) and the WHO Representative’s Office in Tunisia. We are also grateful for the help and continuous assistance of managers and healthcare professionals in the Family Planning Centre of Monastir.

References

- Programme of Action of the United Nations International Conference on Population & Development 5–13 September 1994 Cairo, Egypt ( http://www.iisd.ca/Cairo/program/p00000.html , accessed 25 July 2007).

- Conférence Internationale sur la population et le développement plus 10 ans. République Tunisienne, Ministère de la santé publique, Office national de la famille et de la population, 2004.

- Kols AJ, Sherman JE. Family planning programs: improving quality. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health, Population Information Program, 1998 (Population Reports, Series J, No. 47).

- Williams B. Patient satisfaction: A valid concept? Social science & medicine, 1994, 38(4):509–6.

- Pascoe GC. Patient satisfaction in primary health care: A literature review and analysis. Evaluation and program planning, 1983, 6:185–210.

- Fitzpatrick R. Surveys of patient satisfaction. I. Important general considerations. British medical journal, 1991, 302:31–7.

- Shewhart W. The economic control of quality of manufactured products. New York, D. Van Nostrand, 1934 (reprinted by the American Society of Quality Control, 1980).

- Expanding capacity for operations research in reproductive health: summary report of a consultative meeting: WHO, Geneva, Switzerland, December 10– 12, 2001. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2001.

- Wouters A. Essential national health research in developing countries: health care financing and the quality of care. International journal of health planning and management, 1991, 6:253–71.

- Brook RH, McGlynn EA, Cleary PD. Quality of health care. Part 2. Measuring quality of care. New England journal of medicine, 1996, 335:966–70.

- Brook RH, McGlynn EA, Shekelle PG. Defining and measuring quality of care: a perspective from US researchers. International journal for quality in health care, 2000, 12:281–95.

- Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? Journal of the American Medical Association, 1988, 260:1743–8.

- Hospital accreditation standards. Oakbrook Terrace, IL, Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations,1999.

- Larrabee JH, Bolden LV. Defining patient-perceived quality of nursing care. Journal of nursing care quality, 2001, 16:34–60, 74–5.

- COPE®: client oriented, provider efficient services. New York, AVSC International, 1995.

- Huezo C, Diaz S. Quality of care in family planning: clients’ rights and providers’ needs. Advances in contraception, 1993, 9:129–39.

- Maharaj P, Munthree C. The quality of integrated reproductive health services: perspectives of clients in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Curationis, 2005, 28(1):52–8.

- Alden DL, Do MH, Bhawuk D. Client satisfaction with reproductive health-care quality: integrating business approaches to modeling and measurement. Social science & medicine, 2004, 59(11):2219–32.

- Say L, Foy R. Improving induced abortion care in Scotland: enablers and constraints. Journal of family planning and reproductive health care, 2005, 31(1):20–3.

- Jutand M, Salamon R. La technique de sondage par lots appliquée à l’assurance qualité (LQAS): methodes et applications en santé publique [Lot quality assurance sampling: methods and applications in public health]. Revue d’épidémiologie, médecine sociale et santé Publique, 2000, 48:401–8.

- Ǿvertveit J. The economics of quality: a practical approach. International journal of health care quality assurance, 2000, 13:200–7.