Clare Farrand, Feng J. He and Graham A. MacGregor

WASH is encouraging action groups to be formed in each country. To join, please email WASH (

Wolfson Institute of Preventive Medicine, Barts and The London School of Medicine & Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, London, United Kingdom (Correspondence to Clare Farrand:

Dietary salt raises blood pressure, and raised blood pressure is the single biggest cause of cardiovascular death and disability, accounting for 9.4 million deaths per year worldwide (1). The evidence for the health benefits of population-wide reduction in salt intake is strong. Indeed, salt reduction is one of the most cost-effective measures to prevent cardiovascular disease (CVD) in both developed and developing countries (2).

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs), such as heart attacks and strokes, cancers, diabetes and chronic respiratory disease, account for over 63% of deaths in the world today. Every year, NCDs kill 9 million people under 60 years. The socioeconomic impact is staggering. Such is the problem that in 2011, the United Nations and the World Health Organization (WHO) jointly convened a high level meeting to tackle the growing burden of these “lifestyles diseases”. Salt reduction was recommended as one of the top three priority actions to reduce premature mortality from NCDs by 25% by 2025 (3,4). WHO now recommends a 30% reduction in salt intake by 2025 with an eventual target of 5 g per day for all adults worldwide and lower levels for children based on calorie intake (5). This target was formally adopted by Member States at the 66th World Health Assembly as part of an omnibus resolution to tackle NCDs (6).

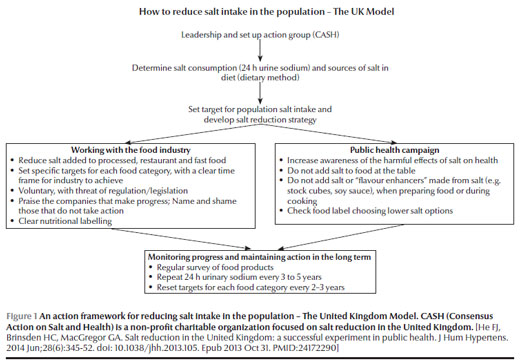

So, the question is how to reduce salt intake in the population to meet the target? World Action on Salt and Health (WASH), a non-profit charitable organization with a mission to reduce salt intake globally, has been working with many countries around the world to help establish effective salt reduction programmes to suit the needs of that particular country to reduce salt intakes (7). For example, it is well established that in developed countries, most of the salt that we eat comes from the food that we buy (75–80%). Therefore the most effective means to reduce salt consumption in these countries is to reduce the salt content of manufactured and catered foods, supplied by the food industry. In developing countries, where most of the salt is added by consumers, a public health campaign plays a major role (8).

Further to this, as diets are becoming more westernized, processed foods are becoming more popular in developing countries, and the food industry is continuing to develop its market in these areas. Therefore, these countries need a combined policy of getting the public to use less salt at home and getting the food industry to reduce the amount of salt added to foods and to adopt a clear labelling system such as the signpost labelling system (9).

In the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR) current salt intakes are very high, with an average intake of > 12 g per person per day in most countries; more than double the amount recommended by WHO.

The disease burden resulting from salt and high blood pressure is very high in the EMR (10). Indeed, it has been identified as a hotspot for cardiovascular and coronary heart diseases. It is estimated that, overall, 47% of the Region’s burden of disease is due to NCDs, and by 2020 it is expected to rise to 60% unless efficient health and nutrition measures are implemented (11).

Currently there are no comprehensive policies to reduce population salt intake in the Eastern Mediterranean countries; however many countries are now starting to take action to formulate salt reduction action plans. Sources of salt in the diet come from both processed foods and salt added during the preparation of food at home. A two-pronged approach, of reformulation and a public awareness campaign would be required to reduce salt intakes.

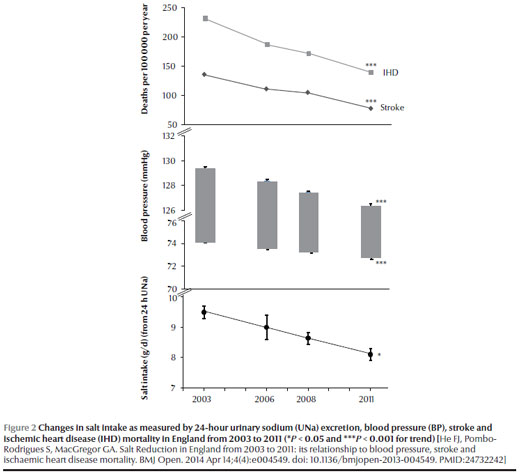

The United Kingdom (UK) has successfully implemented a salt reduction programme (Figure 1). As a result, salt intake has fallen by over 15% over the past 7–8 years, accompanied by a significant fall in population blood pressure and cardiovascular diseases (Figure 2). The UK’s salt reduction model could be adapted by the EMR with appropriate local modifications. A key element of the success of the UK salt reduction programme is the rigorous setting of progressively lower salt targets for over 80 categories of foods, with a clear timeframe and independent monitoring programme. For example, in the UK, salt levels in bread have come down by an average of 20% since the setting of salt targets (12). Bread is an important part of many diets around the world. Reducing salt in bread would have a big impact on salt intakes, and many countries around the world are already focusing their attention on reducing the salt contents of bread.

This example demonstrates how a salt reduction strategy, based on targets in key food categories, can ensure that salt levels are reduced without loss of sales and with no consumer reaction. Governments around the world now need to follow the UK’s lead and set targets on the biggest contributors of salt to the diet so as to prevent thousands of deaths every year; the United States, Canada and Australia are already following the UK’s lead and setting their own voluntary targets.

The UK salt reduction programme has been carried out on a voluntary basis, but this has been underpinned by sustained media pressure, direct pressure on the government and ministers, particularly the public health ministers, so that they would maintain a strong stance with the food industry. Regulatory/legislative approaches are likely to be more effective than voluntary approaches. However, in many countries, the process of legislation is very complicated and this may lead to severe delays in action, as demonstrated by the pace of tobacco legislation (e.g. taxation and banning smoking in all workplaces) coming into force (13).

Countries within the EMR would need to consider their own political processes to determine whether a regulatory/legislative or voluntary approach is more appropriate. Recently, South Africa has started a similar programme based on the UK model, but the salt targets are regulated and the global food companies there preferred a regulatory system rather than a voluntary system as it gave them a level playing field (14). For many other countries, the best way to proceed is to start with a voluntary salt reduction policy with the threat of regulation/legislation and, at the same time, enact the legislation process.

Many organizations concerned with the effects of salt on health and blood pressure are working together to develop “toolkits” to implement salt reduction programmes, which can be used as a guide for countries to follow. It is imperative that all countries adopt a coherent and workable strategy to reduce salt intake in line with their own landscape. In view of the enormous benefits of salt reduction on public health, it would be negligent for any government not to take action now.

References

- Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012 Dec 15;380(9859):2224–60. PMID:23245609

- He FJ, MacGregor GA. Reducing population salt intake worldwide: from evidence to implementation. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2010 Mar-Apr;52(5):363–82. PMID:20226955

- First global ministerial conference on healthy lifestyles and noncommunicable disease control, 28-29 April 2011, Moscow. (http://www.who.int/nmh/events/moscow_ncds_2011/en/, accessed 8 December 2014).

- First global ministerial conference on healthy lifestyles and noncommunicable disease control, 28-29 April 2011, Moscow. http://www.who.int/nmh/events/moscow_ncds_2011/en/ (Accessed 10 June 2013).

- WHO issues new guidance on dietary salt and potassium, 31 January 2013. (http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/notes/2013/salt_potassium_20130131/en/, accessed 8 December 2014).

- World Health Assembly resolution WHA66.10. Follow-up to the Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-communicable Diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013 (http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA66/A66_R10-en.pdf , accessed 8 December 2014).

- World Action on Salt and Health (http://www.worldactiononsalt.com, accessed 8 December 2014).

- Anderson CA, Appel LJ, Okuda N, Brown IJ, Chan Q, Zhao L, et al. Dietary sources of sodium in China, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, women and men aged 40 to 59 years: the INTERMAP study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010 May;110(5):736–45. PMID:20430135

- Pietinen P, Valsta LM, Hirvonen T, Sinkko H. Labelling the salt content in foods: a useful tool in reducing sodium intake in Finland. Public Health Nutr. 2008 Apr;11(4):335–40. PMID:17605838

- Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012 Dec 15;380(9859):2224–60. PMID:23245609

- Mehio Sibai A, Nasreddine L, Mokdad AH, Adra N, Tabet M, Hwalla N. Nutrition transition and cardiovascular disease risk factors in Middle East and North Africa countries: reviewing the evidence. Ann Nutr Metab. 2010;57(3-4):193–203. PMID:21088386

- Brinsden HC, He FJ, Jenner KH, Macgregor GA. Surveys of the salt content in UK bread: progress made and further reductions possible. BMJ Open. 2013;3(6):e002936. 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002936 PMID:23794567

- Brownell KD, Warner KE. The perils of ignoring history: Big Tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is Big Food? Milbank Q. 2009 Mar;87(1):259–94. PMID:19298423

- South Africa leads the world in setting salt reduction targets (http://www.worldactiononsalt.com/news/saltnews/2011/60314.html, accessed 8 December 2014).