FEV1 and FVC pulmonary function reference values among 6-18-year-old children: a multi-centre study in Saudi Arabia

A. Alfrayh,1 T. Khoja,2 K. Alhusain,3 S. Alshehri,3 A. Gad4 andM. Madani3

القيم المرجعية لوظائف الرئة لحجم الزفير القسري في الثانية الأولى والسعة الحيوية القسرية بين الأطفال بعمر 6-18 عاما: دراسة متعددة المراكز في المملكة العربية السعودية

عبد الرحمن الفريح، توفيق خوجة، خالد الحسين، سليمان الشهري، عشري جاد، محمد مدني

الخلاصة: من المهم إقرار قيم مرجعية لوظائف الرئة لكل مجموعة سكانية. وتهدف هده الدراسة إلى التعرف عل القيم المرجعية للقياسات التنفسية لدى الأطفال والمراهقين الأصحاء في المملكة العربية السعودية، واشتقاق معادلات للتنبؤ بقيمها. وقد أجرى الباحثون دراسة مستعرضة شملت تلاميذ وتلميذات أصحاء تتراوح أعمارهم يين 6 18 عاماً، تم اختيارهم عشوائيأ من ستة مناطق إدارية في الملكة العربية السعودية. وجمع الباحثون البيانات من خلال استبيان ومن خلال الفحص المادي باستخدام المقياس التنفسي. واتضح أن قيم حجم الزفير القسري خلال الثانية الأولى والسعة الحيوية القسرية كانت أعلى بمقدار يعتد به إحصائيا لدى الذكور مما هي لدى الإناث. وقد كان الطول هو المتغير الأكثر أهمية من حيث الترابط في القياسات البشرية ذات الصلة بحجم الزفير القسري خلال الثانية الأولى (معامل الارتباط 0.61 = r) وهو أكثر قيمة لدى الذكور (معامل الارتباط 0.7 = r) منه لدى الإناث (معامل الارتباط 0.5 = r) وقد أوضح نمونج التحوف الخطي المتعدد المتغيرات لدى الذكور تفسير التفاوتات لدى 53.9 من حجم الزفير القسري خلال الثانية الأولى و 35.1% مين السعة الحيوية القسرية، أما ما لدى الإناث فقد فسر التفاوتات لدى 25.3% من حجم الزفير القسري خلال الثانية الأولى و 16.5% من السعة الحيوية القصوى. وقد كانت حميع التغيرات في مربع معامل الارتباط R2 ذات أهمية يعتد بها إحصائياً.

ABSTRACT It is important to establish lung function reference values for each population. This study aimed to determine the spirometric reference values for healthy Saudi Arabian children and adolescents and to derive prediction equations for these. A cross-sectional study was conducted among healthy schoolboys and girls aged 6-18 years old, selected randomly from the 6 administrative regions of Saudi Arabia. Data were collected by questionnaire and physical examinations including spirometry. Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) were significantly higher in males than females. Height was the anthropometric variable most strongly correlated with FEV1 (r = 0. 61), more so for males (r = 0.71) than females (r = 0.50). In males the multivariate linear regression model explained 53.9% of FEV1 and 35.1% of FVC variations. In females it explained 25.3% of FEV1 and 16.5% of FVC variations. All changes in R2 were statistically significant.

Valeurs de référence de la VEMS et de la CVF chez des enfants de 6 à 18 ans : étude multicentrique en Arabie saoudite

RÉSUMÉ Il est important d'établir des valeurs de référence de la fonction respiratoire pour chaque population. La présente étude visait à déterminer les valeurs spirométriques de référence chez des enfants et des adolescents saoudiens en bonne santé et à en déduire des équations pronostiques pour ces derniers. Une étude transversale a été menée auprès d'écoliers et d'étudiants des deux sexes en bonne santé et âgés de 6 à 18 ans, sélectionnés aléatoirement dans six régions administratives d'Arabie saoudite. Des données ont été recueillies au moyen d'un questionnaire et d'examens cliniques, y compris la spirométrie. Le volume expiratoire maximal par seconde (VEMS) et la capacité vitale forcée (CVF) étaient nettement supérieurs chez les garçons que chez les filles. La taille était la variable anthropométrique la plus fortement corrélée au VEMS (r = 0, 61), et cette corrélation était plus forte chez les garçons (r = 0,71) que chez les filles (r = 0,50). Chez les garçons, le modèle de régression linéaire multivariée expliquait 53,9 % des variations du VEMS et 35,1 % des variations de la CVF. Chez les filles, le modèle expliquait 25,3 % des variations du VEMS et 16,5 % des variations de la CVF. Toutes les évolutions du R2 étaient statistiquement significatives.

1Department of Paediatrics; 4Department of Family and Community Medicine, College of Medicine, King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (Correspondence to A. Gad:

2Executive Board, Health Ministers' Councilfor the Cooperation Council States, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

3Ministry of Health, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. 4Ministry of Education, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Received: 01/09/13; accepted: 09/04/14

EMHJ, 2014, 20(7): 424-430

Introduction

Pulmonary function tests have been widely used as an objective measure to diagnose and follow up the course of therapy in lung diseases. Their interpretation is highly dependent on reference values (1,2). Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) is widely used to estimate the degree of pulmonary impairment in cases of asthma and other obstructive lung diseases. It has proved to be an excellent method to monitor the progress ofindividual patients (3).

It is important to establish lung function reference values for each population (4). Lung function differs from one population to other, depending on multiple factors including size and shape of the rib cage, respiratory muscles' strength and possibly parenchymal lung development (5). There are also other influences such as environmental pollution, socioeconomic conditions, nutritional status and exercise, which have direct and indirect effects on lung function (6-8).

Currently available reference values of pulmonary functions tests are mostly based on data from European and North American populations which vary from other populations in body stature and ethnic origin (9). Having local spirometric prediction equations will enhance the reliability of the evaluation of lung function (10). ft is therefore important to establish normative values relevant to the ethnic characteristics of the Saudi population.

A literature review yielded only studies among pulmonary patients or adults, but no studies from Saudi Arabia among healthy children (11-13). A study was therefore designed to determine the FEV-1 and forced vital capacity (FCV) reference values for healthy Saudi Arabian children and adolescents and to derive prediction equations for these.

Methods

Study design and sampling

This cross-sectional study was conducted among normal healthy schoolboys and schoolgirls aged 6-18 years. ft used multistage, stratified random sampling in 6 different city regions in Saudi Arabia selected as sites of the study: Riyadh, Mecca, Dammam, Abha, Jizan and Al-Jouff Three schools in each region were randomly selected. All children (n = 5196) registered at the selected schools were invited to participate in the study.

Data collection

Prior ethical approval and permission of the school health authority were obtained. A pilot study including 20 pupils in the Riyadh region was conducted to test the data collection tools and feasibility of the study. The purpose and objective of the study was explained to the pupils and parents by the school health medical staff prior to conduct of the study. The survey ran from September 2009 to April 2010.

The data were collected by well-trained school health medical staff (including Arabic-speaking physicians and nurses) using a 3-part questionnaire (in Arabic language) Part 1 was age and anthropometric measurements of height in cm and weight in kg. Part 2 focused on relevant history such as bronchial asthma, skeletal deformity, chronic bronchitis, chest injury, chest surgery cardiac disease, medical treatment for any respiratory condition in the 2 weeks prior to the study, and cigarette smoking. Part 3 was the physical examination performed by the same medical staff who obtained the history. Examinations focused on ear, nose and throat (ENT), chest, abd omen, skin, and any other relevant systems, e.g. cardiac, musculoskeletal systems.

Only Saudi Arabian nationality subjects were recruited. The exclusion criteria were bronchial asthma, chest cage deformities, previous chest injuries and/or chest operation, cardiac surgery, respiratory illness in the last 2 weeks and cigarette smoking (if 5 cigarettes or more per day).

Prior to performing spirom-etry, the procedure was explained and demonstrated to each child. The pulmonary function test was conducted with the child in a sitting position with the head straight. A minimum of 3 trials were allowed and the best reading was chosen for analysis based on taskforce standard series of the American Task Force standard and European Respiratory Society (14).

Each participant was instructed to take a deep breath and then blow into the mouthpiece as hard and fast as he/she could. The same spirometers were used throughout the study and the tests were performed by the medical staff who were introduced to the study and became acquainted with proper use at the spirometer.

Spirometers used in the study displayed the total valuation of lung function including FVC and FEV1.

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed using SPSS, version 18. Absolute numbers and proportions were used to describe the sample distribution across the different cities and age groups. Means and standard deviations (SD) were used to describe age and lung functions. Independent f-test was used to test the statistical significance of the difference between males and females. Pearson coefficient of correlation (r) was used to investigate the correlation between anthropometric variables and lung functions. Multivariate linear regression model was used to produce coefficient of determination (R2) and prediction equations were developed. Since lung function data from males and females were significantly different, regression analysis was applied to each sex separately.

Results

Out of 5196 children invited to participate in the present study spirometric tests were done for 4526 (87.1%); 133 (2.6%) children refused to participate and 568 (11.0%) were excluded for health reasons [bronchial asthma (75), musculoskeletal diseases (14), smokers (227), cough (161), obesity (26) and ENT problems (34)]. Of the 4526 healthy schoolchildren who agreed to participate in the study 2226 (49.2%) were males and 2300 (50.8%) females. Table 1 shows the age and regional distribution of the children by age and sex.

Table 2 shows that while the mean age of females was higher than males [12.8 (SD 3.4) versus 12.5 (SD 3.4) years] the mean height of males was higher than females [145.9 (SD 17.4) versus 144.5 (SD 14.6) cm]. The differences were statistically significant.

FEV1, FVC and FEV1/FVC were statistically significant higher in males than females (P < 0.001) (Table 2). The Pearson correlation coefficients between the anthropometric and pulmonary function measures are shown in Table 3. Height was the highest correlated anthropometric variable with FEV1 (r = 0. 61). This was true for both males (r = 0.71) and females ( r = 0.50). Age and weight were also correlated with FEV1. All the correlation coefficients were higher for males than females. The same trend was also present in the correlation between an-thropometric variables and FVC (r = 0.49 for height, 0.40 for weight and 0.40 for age). All coefficients of correlation were statistically significantly different between males and females (P < 0.05).

Multivariate linear regression analysis was done for the anthropometric variables and lung functions in children and adolescents (Table 4). In males the model explained 53.9% of FEV1 and 35.1% of FVC variations. In females it explained 25.3% of FEV1 and 16.5% of FVC variations. In the total studied sample 37.3% of variation in FEV1 and 24.1% of FVC were explained by the model. All changes in R2 were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

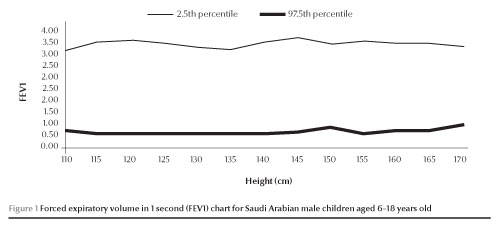

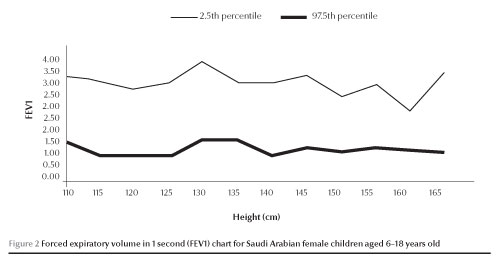

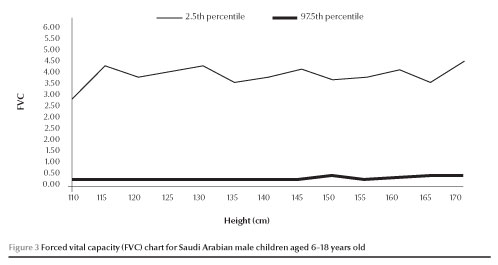

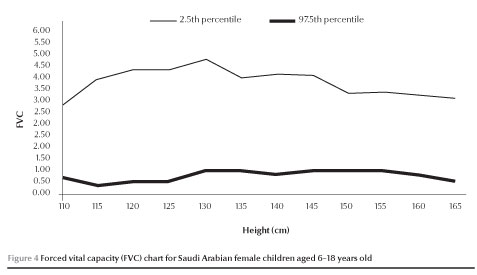

The normal values of FEV1 and FVC (between 2.5 and 97.5 percen-tiles) increased with increases in height in both males and females (Figures 1,2,3 and 4).

Discussion

Pulmonary function tests are widely used as medical decision-making tools. They are relatively simple and non-invasive, but their interpretation depends on reference values (15). Studies have demonstrated that references values based on European populations may not apply in other populations (16). Development of population-specific spirometric prediction equations is essential to ensure the reliability of lung function evaluation (17).

The present study revealed that the mean FEV1 and FVC were 1.78 (SD 0.75) L and 2.19 (SD 0.98) L respectively for males and 1.46 (SD 0.68) L and 1.80 (SD 0.92) L respectively for females. A similar study in Jordan included 204 males and 224 females aged 7-18 years and found that the mean FEV1 ranged from 1.2 to 4.0 L, while FVC ranged from 1.2 to 4.5 L among children (18). Trabelsi et al. in Tunis reported that the mean FVC was 2.37 (SD 0.81) L and the mean FEV1 was 2.08 (SD 0.7) L for Tunisian children and adolescents aged 6-16 years (19). The variation in mean values as well prediction equations is widely accepted and attributed to age, sex, body stature, ethnic, genetic and environmental differences (20).

FEV1 and FVC were higher in males than females in the present work. Studies in different parts of the world agreed with this finding. A study conducted at The Aga Khan University Hospital in Pakistan found that mean FEV1 and FVC were higher in males than females in all age groups (9). Manzke et al. reported that the growth pattern is different in males than females and expected that lung function prediction equations should be different for both sexes (21). Their finding was in agreement with the present study results whereby males and females had 2 different prediction equations. Also Thurlbeck in the early 1980s studied the lung morphometry of36 boys and 20 girls aged 6 weeks to 14 years and found that boys tended to have larger lungs per unit of stature and that the total number of alveoli was greater in males than females (22).

The relationship of anthropomet-ric measurements and values of FEV1 and FCV was assessed by linear logarithmic and power models, but simple linear models were found to be the best predictive equations for lung functions. The present study revealed that height was positively associated with reference values of pulmonary function in children and adolescents. Consistent with this finding Barcala et al. in Spain found that height was the independent variable with the greatest predictive power for lung function (23). Also Vijayan et al. in India reported that among 7-19-year-olds height influences the prediction equations to a greater extent in males than females, but that weight had a greater influence in girls (24). In Hong Kong a study among Chinese children and adolescents has noted that the most important variable affecting the spirometric variables values was height (25). The effect ofheight may be attributed to the fact that during childhood the lungs increase in proportion to the increase in height and the increase in height leads to an increase in lung volume and capacity. Furthermore, height can be accurately measured without the use of special equipment or techniques (26).

The present work shows that age was one of the determinants of spiro-metric values. Chatterjee and Saha in India reported that age and height were significant predictors of FEV1 and FVC (27). Borsboom et al. studied the pubertal curves of ventilator function and reported that age improved the power of prediction equations because it was correlated with growth and development, particularly the strength of intercostal muscles (28).

The present study had some limitations. It only developed reference values for 2 lung function parameters (FEV1 and FCV). Although 3 schools were selected from each city the number of participants was not equal across cities due to variations in exclusions due to morbidity and refusal to participate among schoolchildren.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study has developed normal FEV1 and FCV values and prediction equations for Saudi Arabian children and adolescents (618 years). These national reference values need to be used and tested by health-care providers in Saudi Arabia. A prospective study using repeated measures and including all lung function parameters is recommended among Saudi children.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge and thank the school health physicians and nurses for helping with the data collection. We also thank Professor Mam-mdouh Al-Messeiry for his assistance in drawing the reference values charts.

Funding: the study was funded by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Saudi Arabia.

Competing interests: none declared.

References

- Lin FL, Kelso JM. Pulmonary function studies in healthy Filipino adults residing in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999 Aug;104(2 Pt 1):338-40. PMID:10452754

- Koopman M, Zanen P, Kruitwagen CLJ, Van der Ent CK, Arets HGM. Reference values for paediatric pulmonary function testing: The Utrecht dataset. Respir Med. 2011 Jan;105(1):15-23.

- Vaughan TR, Weber RW, Tipton WR, Nelson HS. Comparison of PEFR and FEV1 in patients with varying degrees of airway obstruction. Chest. 1989 Mar;95(3):558-62. PMID:2920583 '

- Rochat MK, Laubender RP, Kuster D, Braendli O, Moeller A, Mansmann U, et al. Spirometry reference equations for central European populations from school age to old age. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e52619. 10.1371/journal.pone.0052619 PMID:23320075

- Cotes JE. Lung function throughout life: determinants and reference values. In: Cotes JE, editor. Lung Function: Assessment and Application in Medicine. 5th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1993. pp. 445-513.

- Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999 Jan;159(1):179-87. PMID:9872 837

- Ghazal-Musmar S, Musmar M, Minawi WA. Comparison of peak expiratory flow rates applying European and Iranian equations to Palestinian students. East Mediterr Health J. 2010 Apr;16(4):386-90. PMID:20795421

- Hellmann S, Goren AI. The necessity of building population specific prediction equations for clinical assessment of pulmonary function tests. Eur J Pediatr. 1999 Jun;158(6):519-22. PMID:10378404

- Ali Baig MI, Qureshi RH. Pulmonary function tests: normal values in non-smoking students and staff at the Aga Khan University, Karachi. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2007 May;17(5):265-8. PMID:17553322

- Nysom K. ULrik CS, Hesse B, Duksen A. Published models and local data can bridge the gap between reference values of lung function for children and adults. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:1591-8. PMID:9230253

- Al Ghobain MO, Alhamad EH, Alorainy HS, Al Hazmi M, Al Moamary MS, Al-Hajjaj MS, et al. Spirometric reference values for healthy nonsmoking Saudi adults. Clin Respir J. 2014 Jan;8(1):72-8. PMID:23800240

- Habib SS, Abba AA, Al-Zoghaibi MA, Subhan MM. Reference range values of fractional exhaled nitric oxide in healthy Arab adult males. Saudi Med J. 2009 Nov;30(11):1395-400. PMID:19882049

- Abdullah AK, Abedin MZ, Nouh MS, Al-Nozha M. Ventilatory function in normal Saudi Arabian adults. Observations and comparison with some Western and Eastern reference values. Trop Geogr Med. 1986 Mar;38(1):58-62. PMID:3961909

- Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al.; ATS/ERS Task Force. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005 Aug;26(2):319-38. PMID:16055882

- Horn PS, Pesce AJ. Reference intervals: an update. Clin Chim Acta. 2003 Aug;334(1-2):5-23. PMID:12867273

- Golshan M, Nematbakhsh M, Amra B, Crapo RO. Spirometric reference values in a large Middle Eastern population. Eur Respir J. 2003 Sep;22(3):529-34. PMID:14516147

- Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, Crapo RO, Burgos F, Casa-buri R, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2005 Nov;26(5):948-68. PMID:16264058

- Sliman NA, Dajani BM, Shubair KS. Pulmonary function in normal Jordanian children. Thorax. 1982 Nov;37(11):854-7. PMID:7164005

- Trabelsi Y, Ben Saad H, Tabka Z, Gharbi N, Bouchez Buvry A, Richalet JP, et al. Spirometric reference values in Tunisian children. Respiration. 2004 Sep-Oct;71(5):511-8. PMID:15467330

- Bhagyalakshmi O, Prasad CE. Spirometric studies of the subjects in an active area of Hyderabad A.P. Indian J Environ Health. 2002 Apr;44(2):113-7. PMID:14503383

- Manzke H, Stadlober E, Schellauf HP. Combined body ple-thysmographic, spirometric and flow volume reference values for male and female children aged 6 to 16 years obtained from "hospital normals". Eur J Pediatr. 2001 May;160(5):300-6. PMID:11388599

- Thurlbeck WM. Postnatal human lung growth. Thorax. 1982 Aug;37(8):564-71. PMID:7179184

- Gonzalez Barcala FJ, Cadarso Suârez C, Valdés Cuadrado L, Leis R, Cabanas R, Tojo R. Valores de referencia de funciôn respiratoria en ninos y adolescentes (6-18 anos) de Galicia. [Lung function reference values in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 years in Galicia]. Arch Bronconeumol. 2008 Jun;44(6):295-302. PMID:18559218

- Vijayan VK, Reetha AM, Kuppurao KV, Venkatesan P, Thilaka-vathy S. Pulmonary function in normal south Indian children aged 7 to 19 years. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2000 Jul-Sep;42(3):147-56. PMID:11089318

- Ip MS, Karlberg EM, Karlberg JPE, Luk KDK, Leong JCY. Lung function reference values in Chinese children and adolescents in Hong Kong. I. Spirometric values and comparison with other populations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000 Aug;162(2 Pt 1):424-9. PMID:10934064

- Ip MS, Karlberg EM, Chan KN, Karlberg JP, Luk KD, Leong JC. Lung function reference values in Chinese children and adolescents in Hong Kong. II. Prediction equations for ple-thysmographic lung volumes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000 Aug;162(2 Pt 1):430-5. PMID:10934065

- Chatterjee S, Saha D. Pulmonary function studies in healthy non-smoking women of Calcutta. Ann Hum Biol. 1993 Jan-Feb;20(1):31-8. PMID:8422165

- Borsboom GJ, Van Pelt W, Quanjer PH. Pubertal growth curves ofventilatory function: relationship with childhood respiratory symptoms. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993 Feb;147(2):372-8. PMID:8430961

Childhood very severe pneumonia and meningitis related hospitalization and death in Yemen, before and after introduction of H. influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine

S.M. Banajeh,1 O.Ashoor2 and A.S. Al-Magramy2

معدلات الإدخال في المستشفيات والوفيات ذات الصلة بالالتهاب الرئوي والتهاب السحايا الشديدة جدا في اليمن قبل وبعد إدخال لقاح |لمستذمية النزلية من النمط بي

سالم محسن باناجه، عمر عاشور، أحمد شمان المقرمي

الخلاصة: لفند أدرج لقاح المستدمية النزلية من النمط بي في البرنامج اليمني للتمنيع في عام 2005. وتقارن هذه الدراسة في معدلات الإدخال في المستشفيات والوفيبات ذات الصلة بالالتهاب الرئوي الشديد جداً والالتهاب السحائي الناجم عن جميع الأسباب قبل وبعد إدخال لقاح المستدمية النزلية المتقارن من النمط بي ، وتعرض نتائج الترصد لالتهاب السحايا الجرثومي في عام 2010. وهي دراسة استعادية أجريت على البيانات التي جمعت في الفترة 2000-2010 وشملت جميع الأطفال الذين تراوحت أعمارهم بن شهرين و60 شهراً في المستشفى الرئيسي لطب الأطفال في صنعاء. وقد اتضح وجود انخفاضات يعتد ببا إحصائياً ومثيرة للاهتمام في معدلات الإدخال إلى المستشفى والموت الناجم عن جميع أسباب التهابات السحايا في الفتزة التي سبقت إدخال اللقاح مقارنة بالفترة التي تلت إدخال اللقاح. إلا أن معدل الإدخال إلى المستشفى والوفيات بسبب الالتهاب الرئوي الشديد جدآ لم يتحسن إلا قليلاً، وكانت هناك بينات على تناقص، ولكن دون أن يكون له ميل يعتد به إحصائياً، مما يدل على أن الالتهاب الرئوي الشديد جداً كان بمثابة نقطة نهائية غير نوعية تترافق بأسباب متعددة للأمراض (منها جرثومي ومنها فيروسي). ولايزال الالتهاب الرئوي الشديد جدا هو السبب الأكبر انتشارا للأمراض الشديدة وللموت بن صغار الأطفال، ولاسيما من يقل عمره عن 12 شهراً.

ABSTRACT Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine was included in the Yemen immunization programme in 2005. This study compared the rates of very severe pneumonia and all-cause meningitis hospitalization and death, before and after introduction of conjugate Hib vaccine, and reports the results of the 2010 bacterial meningitis surveillance. A retrospective analysis was made of data collected for 2000-2010 for all children aged 2-60 months in the main children's hospital in Sana'a. Compared with the pre-Hib vaccination period, the post-Hib period showed significant and impressive reductions in the rates of hospitalization and death for all-cause meningitis. However, hospitalization and death for very severe pneumonia improved only modestly, and there was evidence of a decreasing but non-significant trend indicting that very severe pneumonia was a non-specific endpoint with multi-etiologies (both viral and bacterial). Very severe pneumonia remains the leading cause of severe morbidity and death for young children, particularly those aged < 12 months.

Hospitalisations et décès dus à une pneumonie très sévère ou à une méningite chez l'enfantau Yémen, avant et après l'introduction du vaccin H. influenzae de type b (Hib)

RÉSUMÉ Le vaccin contre Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) a été inclus dans le programme de vaccination du Yémen en 2005. La présente étude a comparé les taux d'hospitalisation et de décès dus à une pneumonie très sévère et à une méningite toutes causes confondues, avant et après l'introduction du vaccin Hib conjugué ; elle a par ailleurs présenté les résultats de la surveillance de la méningite bactérienne de 2010. Une analyse rétrospective a été menée afin de recueillir des données sur la période de 2000 à 2010 pour tous les enfants âgés de 2 à 60 mois dans le grand hôpital pour enfants de Sanaa. Par rapport à la période précédant la vaccination par le Hib, la période suivant cette dernière a présenté des réductions significatives et remarquables dans les taux d'hospitalisation et de décès pour méningite toutes causes confondues. Toutefois, les taux d'hospitalisation et de décès pour pneumonie très sévère n'ont diminué que modestement. Des éléments montrent certes une tendance à la baisse, mais non significative, et indiquent que la pneumonie très sévère n'était pas un critère d'évaluation spécifique lorsque les étiologies étaient multiples (à la fois virale et bactérienne). La pneumonie très sévère reste la cause principale de morbidité sévère et de décès chez le jeune enfant, notamment chez l'enfant de moins de 12 mois.

1Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, University of Sana'a, Sana'a, Yemen (Correspondence to S. Banajeh:

Received: 23/06/13; accepted: 14/01/14

EMHJ, 2014, 20(7): 431-441

Introduction

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) is an important cause of meningitis and pneumonia-related morbidity and mortality among children under 5 years old (l) The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that all countries should include Hib vaccine in their national immunization programme and, where possible, these countries should measure the impact of the vaccine on the burden of the disease (2,3). Studies from many developing countries have reported significant progress towards almost total elimination of invasive Hib diseases after the introduction of vaccination (4-6). In the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR), a study in Morocco reported that the introduction of Hib vaccine reduced Hib meningitis by 75% (7). Hib vaccine was also reported to reduce non-culture-confirmed meningitis (6,8), and hospital laboratory data showed a significant reduction in suspected bacterial meningitis of unknown etiology (9,10).

The effect of Hib vaccine on radi-ologically-confirmed pneumonia in several case-control studies found reductions in reported cases of 22%-55% (1-13). However, in at least one study the majority of cases were of mild to moderate severity and only 2.5% had severe lobar pneumonia. That study suggested that the effect of Hib vaccine on pneumonia severity needs investigation (ll). A recent systematic review of the literature on the effect of Hib vaccine on the incidence, severity, morbidity and mortality of childhood pneumonia reported a summary effect of 4% on clinical pneumonia, 6% on clinically severe pneumonia and 18% on radiologically-confirmed pneumonia (14), but no summary effect on WHO-defined very severe pneumonia was reported. Cases ofvery severe pneumonia tend to have low blood culture results, may have both viral and bacterial etiology and some may have concomitant meningitis (15).

It is not known whether the introduction of Hib vaccine reduces the prevalence of very severe pneumonia and all-cause meningitis hospitalization and related mortality, and whether it may be used as a proxy for Hib vaccine effectiveness in resource-poor health settings, where laboratory services may be unreliable and suboptimal and where most affected children may have attended after using antibiotics for several days before hospitalization.

Yemen is a least developing country, and the only low-income country in the Arabian Peninsula. In early 2005, the GAVI Alliance supported the introduction of Hib vaccine as part of the national immunization programme, given in combination with diphtheria/ polio/tetanus and hepatitis B vaccine. Three doses of the combined vaccines are given free ofcharge at the age of6, 10 and 14 weeks. In early 2011, conjugate pneumococcal vaccine was included in the national immunization programme, and rotavirus vaccine was introduced in August 2012, both supported by the GAVI Alliance. The objectives of this study in Sana'a were: to compare the rates of very severe pneumonia and all-cause meningitis hospitalization and death and to compare the inpatient case fatality rate (CFR) of both, before and after introduction of conjugate Hib vaccine to the Yemen national immunization programme; and to report the results and the outcome of the 2010 bacterial meningitis surveillance in Al-Sabeen Hospital, 5 years after the introduction of Hib vaccine.

Methods

Study setting and background

The study was conducted in Al-Sabeen Hospital for Women and Children, which is the main paediatric hospital located in Sana'a, the capital ofYemen. This government-run hospital provides both primary and secondary care to the urban and rural population of Sana'a city and the surrounding areas (approximately 3 million inhabitants). The services include walk-in outpatient clinics during working days. It has a 15-bed emergency unit that provides paediatric and neonatal services 24 hours a day, supported by laboratory and radiology services. The hospital has 2 paediatric medical wards (45 beds), an infectious isolation ward (20 beds) and a paediatric surgical ward (22 beds). The coverage rate of Hib vaccine (dose 3) in the catchment areas and the national coverage rate exceeded 85% (Table 1).

Case management

Children aged 1 months to 5 years who attend the emergency unit with clinically very severe pneumonia and those attending with clinical features of meningitis are usually assessed by the on-duty paediatrician. An intravenous line is usually established and blood is usually collected for full blood count, C-reactive protein and blood smears for malaria. Chest X-ray for very severe pneumonia is also done routinely. For children with suspected meningitis, after obtaining parents' verbal consent, lumbar puncture (if not contraindicated) is usually performed to examine the CSF. CSF samples are usually sent for cell count and differential, protein and glucose. Gram stain and CSF culture is usually done in the hospital when reagents and facilities are available or samples are immediately sent to private laboratories adjacent to the hospital when facilities are not available. Ifparents are unable to pay for these private services, Gram stain and CSF culture are usually not done. In recent years, with WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean (EMRO) technical and financial support, almost all CSF samples have been investigated in the hospital laboratory. However, in 2010, only 48% and 65% of samples were Gram stained or cultured respectively (see data in the Results) indicating that these services are still suboptimal. Cases with very severe pneumonia are usually started with intravenous am-picillin and gentamicin, with oxygen supplementation via nasal catheter at a rate of 2 L/min. Cases with suspected meningitis are usually started on intravenous ampicillin and a 3rd-generation cephalosporin.

Bacterial meningitis surveillance

Since 2006 Al-Sabeen Hospital has been a major site of the bacterial meningitis surveillance network in Yemen, with technical and financial support from EMRO. The hospital laboratory service, however, is suboptimal because cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) results only occasionally report the results of Gram stain of organisms if regents are available, and culture is sometimes not done. Latex agglutination to detect bacterial antigen is not available, and cultures, if performed, are usually reported to have no growth. Most children with very severe pneumonia or suspected meningitis have usually been on oral or parenteral antibiotics for several days before attending the emergency unit.

Study design

This was an observational, retrospective analysis of data collected over an 11-year period (2000-2010) and of the 2010 bacterial meningitis surveillance data collected in special forms designed and supplied by EMRO.

Out of a total of 21 701 children who attended the outpatient clinics in 2010, 5164 attended the paediatric emergency unit and were the basis of the main study, and 305 children aged 2-60 months with suspected bacterial meningitis were included in the active surveillance reported here.

Data collection

Data collection at the hospital

Information recorded for each hospitalized patient at Al-Sabeen Hospital include the date of admission, age and sex of the child and inpatient diagnoses recorded in the admission log book. The death log book records the name, age, sex of the child and cause and date of death, and are signed by both the attending paediatrician and nurse. At the end of every calendar year, summary data on all children hospitalized and total deaths for each inpatient paediatric ward are obtained from the records and statistics unit. Information on the causes of hospitalization and death by age group (< 12 months, 12 months-5 years and > 5 years) and the malefemale proportions of each age group are obtained from the admission, discharge and death log books of each paediatric ward. Data are collected using proforma datasheets and then entered using Microsoft Excel spreadsheets.

Definitions

The clinical definition of very severe pneumonia used at this hospital is cough, rapid breathing and lower chest in-drawing and at least one of the following danger signs: clinical cyanosis, unable to breastfeed or drink, lethargy or not alert. The clinical definition of meningitis is fever of sudden onset with one or more one of the following relevant signs: convulsions, neck stiffness, bulging anterior fontanel in children aged < 12 months, poor sucking, altered consciousness, irritability, toxic appearance and/or purpuric rash.

Pre-/post-Hib vaccination study

For this study, data of the total children aged 2-60 months who were hospitalized and died with WHO-defined very severe pneumonia and all-cause meningitis were included. We stratified the data according to age group and subgroups (< 12 months and 12-60 months), and sex (male and female) for each year. Data for children hospitalized with severe gastroenteritis and dehydration were also included in the study analysis as a control group. Patients were divided into 2 groups related to the year of Hib vaccine introduction (2005): the pre-Hib vaccine period (2000-2004) and the post-Hib vaccine period (2006-2010). The year of Hib vaccine introduction, i.e. the transitional year, was excluded.

Bacterial meningitis surveillance

For the 2010 bacterial meningitis surveillance, the data was entered in Excel spreadsheets. Information for each child with suspected clinical meningitis included the child's code number (without names), age (months), sex, vaccination status (yes, no or unknown) and treatments (oral or parenteral antibiotic) given prior to hospitalization. CSF specimens that were analysed and results that included cell count, protein, glucose, Gram stain and culture were recorded. Based on the recent WHO recommended surveillance standard for case identification of bacterial meningitis (16), we defined a child to have probable bacterial meningitis if the CSF was purulent (cloudy and/or cell count > 100/mm3), and to have presumptive bacterial meningitis if the CSF was Gram-stain positive. Gram-stained positive results can rapidly provide evidence of bacterial meningitis even if culture fails (16). No latex agglutination tests were available. The outcome of a child in the surveillance was defined as alive and well on discharge or treatment failure (death or developed neurological complication).

Ethical considerations

Because the data were obtained retrospectively, no names were recorded, none of the parents were interviewed and none of the children were followed up, and we were therefore advised that ethical approval was not needed for this study. However, approval to conduct this study was obtained from the hospital director, and the head of the academic unit ofAl-Sabeen Hospital.

Data management and statistical analysis

Summary data of each calendar year (2000-2010) were imported into SPSS software, version 11.5. Variables created include counts of total number of hospitalizations, number of cases and rates of very severe pneumonia, all-cause meningitis and diarrhoea-related hospitalization and death. Variables for the proportions by sex and 2-60 months age group (and < 12 and > 12 months subgroups) for both hospi-talization and the outcome (alive on discharge or dead) were also analysed. No etiological diagnosis was available in the hospital records. We used Mann-Whitney non-parametric test to compare proportions in the 2 periods (pre- and post-Hib). We measured and compared the median and interquartile range (IQR). We calculated the percentage of median difference with 95% confidence interval (CI) between the 2 periods. We also measured and compared inpatient CFR for each age-related subgroup hospitalized before and after Hib vaccine introduction. For this analysis we used simple binary logistic regression with logit link function. The sum of each subgroup and the proportion who died (case fatality) was the binary variable (event: death). In the model we included the pre- and post-Hib period variable which was also included as a predictor factor.

We also conducted descriptive analysis of the bacterial meningitis surveillance data for 2010. Using logistic regression controlling for age and sex we compared the unvaccinated with those vaccinated in terms of 2 main outcomes: development of purulent CSF (probable bacterial meningitis) and treatment outcome on discharge: alive and well, or treatment failure (death and or neurological complications). The statistical package calculated the odds ratio (OR), 95% CI and P-value.

For all the statistical analysis, the significant level was set at < 0.05. Analysis was performed using Minitab software, version 13.2.

Results

Rate of hospitalization in the pre- and post-Hib periods

Between 2000 and 2010 inclusive, 37 323 children aged 2-60 months were hospitalized. WHO-defined very severe pneumonia, all-cause meningitis and diarrhoea-related hospitalization accounted for 10 745 (28.8%), 2526 (6.8%) and 6523 (17.5%) cases respectively. The proportion of cases for each disease who were < 12 months old were 75%, 74% and 74% respectively. Of the total 1652 deaths, the number of very severe pneumonia, meningitis and diarrhoea-related deaths were 271 (16.4%), 181 (11.0%) and 273 (16.5%) respectively.

Among those aged 2-60 months, the post-Hib period (2006-2010) saw statistically significant median reductions compared with the pre-Hib period (2000-2004) in the rate of hospitalization for very severe pneumonia [23% (95% CI: 16% to 61%] (P = 0.0122) and meningitis [34% (95% CI: 12% to 49%] (P = 0.0283), while for diarrhoea hospitalization the difference was not significant [26% (95% CI: -16% to 73%]. Among the < 12 months and > 12 months subgroups the median reductions in hospitalization for very severe pneumonia were statistically non-significant [9% (95% CI: -2.2% to 69%] and significant [59% (95% CI: 18% to 68%] respectively; and for meningitis the reductions were significant [33% (95% CI: 0% to 48%] and non-significant [34% (95% CI: -68% to 53%] respectively for the same age groups. In contrast, the median reductions in diarrhoea-related death were non-significant for both age subgroups [17% (95% CI: -29% to 75%) and 48% (95% CI: -64% to 68%) respectively] (Table 2).

Rate of inpatient death in the pre- and post-Hib periods

For the 2-60 months age group the rate ofvery severe pneumonia death showed a median reduction of 60% (95% CI: -36% to 71%) in the post-Hib period, a modest reduction but not statistically significant. The all-cause meningitis death rate was significantly reduced with a median reduction of 69% (95% CI: 50% to 87%), while diarrhoea-related death showed a non-significant median reduction of 23% (95% CI: -11% to 50%). For children aged < 12 months and 12-60 months, although the median reductions for very severe pneumonia were non-significant [57% (95% CI: -23% to 68%) and 89% (95% CI: -200% to 100%) respectively], the magnitude of the reduction was clinically important. Significant reductions in meningitis-related death rates of 61% (95% CI: 33% to 76%) and 100% (95% CI: 60% to 100%) respectively was observed. For diarrhoea-related death, the median reduction was not significant for either age subgroup [22% (95% CI: -14% to 50%) and 25% (95% CI: 0% to 50%) respectively] (Table 2).

Inpatient CFR showed statistically significant reductions in the post-Hib period for very severe pneumonia and all-cause meningitis but not for diarrhoea-related hospitalization (Table 3).

Epidemiology of bacterial meningitis in 2010

The characteristics of 305 children aged 2-60 months (62% males) with suspected bacterial meningitis recorded in the 2010 bacterial meningitis surveillance in Al-Sabeen Hospital are shown in Table 4. The vaccination status showed 66% were Hib vaccinated, 28% unvaccinated and 6% vaccination status unknown. Of the 305 cases, 83% were on antibiotics and 65% had CSF cultured. The rate of purulent CSF (probable bacterial meningitis) was 17%, almost 3 times more common in the unvaccinated compared with the vaccinated group (Table 4).

Of the 53 children with purulent CSF, 39 (74%) were aged < 12 months. Among the treatment failures (n = 12), 4 (33%) had purulent CSF compared with 49 (17.0%) of the successfully treated group (n = 239). Ofthe 12 treatment failures 8 (66.7%) were unvac-cinated. Among the 12 failures, there were 3 (25%) deaths, while 4 (33%) developed obstructive hydrocephalus, 3 (25%) spastic cerebral palsy and 2 (17%) subdural fluid collection.

Gram staining was performed in only 147 (48%) ofthe collected samples of CSF, of which 40 cases (46%) were unvaccinated and 95 (47%) vaccinated. Gram-positive diplococcic pairs (Streptococcus pneumoniae) were reported in 11 (28%) and 10 (11%) respectively. Only 1 case of Gram-negative coco-bacilli (H. influenzae) was recorded in the vaccinated group. There were 3 deaths (3.4%) and 5 cases (5.8%) of neurological complications among the unvaccinated children, compared with no deaths and 4 (2%) cases ofwith neurological complications among the vaccinated children.

Binary logistic regression analysis was done controlling for age and sex with the vaccinated group as the reference. The unvaccinated group had a statistically significant higher proportion ofcases with purulent CSF (27/86, 31.4%) compared with the vaccinated children (23/201, 11.4%) (adjusted OR=3.5; 95% CI: 1.8-6.6) (P < 0.001). Treatment failure (death/neurological complications) among the unvac-cinated group (8/87, 9.2%) was also significantly higher compared with the vaccinated group (4/199, 2.0%) (adjusted OR = 3.8; 95% CI: 1.1-13.9) (P = 0.045) (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, information on WHO-defined very severe pneumonia and all-cause meningitis-related hospitaliza-tion and death, before and after Hib vaccine introduction is reported for the first time in Yemen. The statistically significant decline in the number of hospitalizations for all-cause meningitis among children aged 2-60 months in the post-Hib period (median reduction of 34%) is strongly evidence of the impact of this intervention. The decline in meningitis-related death rates among the 2-60 months group and subgroups (median reductions of 69%, 61% and 100%) is also a striking and important finding, and reflects an impressive effect of the introduction of Hib vaccine.

The impact of Hib vaccine on all-cause very severe pneumonia-related hospitalization and death showed a modest decline in our study, since very severe pneumonia is a non-specific end-point that can be caused by multiple pathogens of bacterial or viral origin. In addition, Hib pneumonia is difficult to identify and there is no sensitive and specific test to diagnose Hib-related pneumonia death.

The significant reduction in the proportion of hospitalized cases of very severe pneumonia among those aged 2-60 months (23% median reduction) was mainly due to the statistically significant median reduction of 59% among those aged > 12 months. There was no concomitant statistical significant reduction in the rate of very severe pneumonia-related death among children aged 2-60 months and/or < 12 months. However, the median reduction of 60% and 57% respectively in death was clinically important even though the 95% CI included zero. The magnitude of the impact of Hib vaccine on clinically important outcomes should be considered (17).

The non-significant reduction in hospitalization among the < 12 months age group may indicate that H. influenzae is less likely to be the etiology pathogen among this subgroup. Al-Sabeen Hospital was one of the sites of the Severe Pneumonia Evaluation Antimicrobial Research (SPEAR) study performed in 7 countries including Yemen. In this study, the bacterial isolates obtained from blood and lung aspirates in 110 children aged 2-59 months, Staph. aureus (n = 47) was the most common organism isolated (18). Blood cultures of the very severe pneumonia cohort (n = 151) in the Al-Sabeen site of the SPEAR study, showed that 28 (19%) were positive for bacterial growth. Of those, Staph. aureus isolates were 23 (82%), of which 21 (91%) were isolated from children aged < 12 months [Banajeh S, unpublished data]. It is therefore possible that in this study very severe pneumonia-related hospitalization among this age group was most likely due to other pathogens, and Staph. aureus may be an important etiology. A recent study from India reported that the most common bacterial pathogen isolated from blood/pleural fluid cultures in cases of childhood pneumonia was Staph. aureus among children aged < 5 years (19). A recent review showed that Hib vaccine was associated with a 6% significant reduction in severe pneumonia, 18% non-significant reduction in radiologically-confirmed pneumonia and a 7% non-significant reduction in pneumonia mortality (20). This could explain our findings of modest reductions in very severe pneumonia-related hospitalization and death in the post-Hib period, particularly among the < 12 months subgroup. Our results concerning very severe pneumonia before and after Hib vaccine introduction are further supported in a recent analysis of data to estimate severe pneumonia-related morbidity and mortality for 192 countries including Yemen (21). In that review, Rudan et al. estimated that for Yemen in 2010 cases of all-cause severe morbidity due to acute lower respiratory infections, unadjusted and adjusted for Hib vaccine, were 137 073 and 131 540 respectively for children aged under 59 months (4% reduction), and in 2011 the number of deaths were 11 173 and 11 306 (1.2% increase) (21).

Pneumococcal vaccine was introduced into the Yemen national immunization programme in early 2011. Based on a recent review, pneumococcal vaccine may result in a significant 29% reduction in radiologically-con-firmed pneumonia, significant 11% reduction in severe pneumonia and non-significant 18% reduction in pneumonia mortality (20). Decline in pneumonia-related severity and death due to the 2 vaccines could result in an increase of pneumonia due to Staph. aureus, and other non-vaccine preventable pathogens. However, vaccine interventions alone may not significantly reduce the burden of severe pneumonia morbidity and mortality at both the community and health facility level. Interventions that reduce the prevalence ofmajor risk factors such as malnutrition, non-breastfeeding, use of solid fuels in the house and crowding at the community level (20,21) need consideration. Other interventions that ensure adequate oxygen supply to hospitals with pulse oximeter to detect hypoxaemia, effective and adequate antibiotic supplies and early/easy access to health facilities are also crucial. All these interventions are important to achieve a dramatic reduction in severe pneumonia morbidity and mortality (20,21).

Although introduction of Hib vaccine in Kenya reduced the incidence of Hib disease by 12% from baseline (22), a recent study reported inpa-tient pneumonia CFR trends from 9 health facilities remained unchanged before and after Hib vaccine introduction mainly due to variability of CFRs across the study sites (23). However, our study showed a significant reduction in pneumonia CFRs after Hib vaccine introduction in a single health facility. It is unlikely that these reductions in very severe pneumonia and meningitis-related CFR in our study are due to improvements in the quality of the hospital care, since the rates of diarrhoea-related hospi-talization and in-hospital mortality and CFR remained unchanged before and after Hib vaccine introduction.

This study had several limitations. First, the data analysis was retrospective and obtained from a single health facility. However, Al-Sabeen Hospital is the major paediatric health facility and attracts more than 75% of sick children in the catchment areas, and the data collected were large with reasonably accurate information on cause-specific hospitalization and death according to age group and sex. Hospital-based studies in developing countries have shown good agreement with community findings regarding causes of childhood deaths (24), and our study data may be sufficient to reflect the disease burden at the community level.

Second, risk factors for hospitalization and inpatient death such as healthcare seeking behaviour, malnutrition and other socioeconomic risk factors were not included in the study due to lack of information. We assumed that these risk factors for severe gastroenteritis are generally similar to those for very severe pneumonia and meningitis. The lack of association between Hib vaccination and severe gastroenteritis indicates an absence of major bias. Veirum et al. reported good consistency between these settings, with risk factors having the same direction of association when comparing risk factors for mortality at both hospital and community levels (25).

In countries such as Yemen with inadequate vital registration, accurate inpatient data about childhood death by cause, sex and age group could be an important tool to provide robust population cause-specific mortality fractions (26). The data of Al-Sabeen Hospital bacterial meningitis sentinel surveillance in 2010 showed that latex agglutination testing was not available to detect possible bacterial pathogens. CSF culture was extremely unlikely to yield bacterial growth, since 88% of the children with suspected meningitis were on antibiotics prior to hospital admission. With only 65% of the collected CSF samples cultured, 48% of CSF samples Gram stained and no available latex agglutination testing, it is clear that, despite EMRO technical and financial support, the hospital laboratory services remain suboptimal. Our findings of 1 case of H. Influenzae identified by Gram stain compared with 22 of Strep. pneumoniae among 305 children aged < 5 years suggests a strong impact of the Hib vaccine in the catchment areas. Meningitis hospital data were reported to be similar in a network of hospitals and may represent that in the community (27). With the extensive use of antibiotics in suspected bacterial meningitis prior to hospitalization, CSF Gram stain has been reported to be a more useful and reliable method to identify CSF pathogens with a high sensitivity and specificity (98.3% and 98.7% respectively) than CSF culture or latex agglutination testing, and should be encouraged in poor-resource settings (28). Our study showed that unvaccinated children are more likely to have purulent CSF, and more likely to die or develop permanent neurological complications.

We presume that the rates of viral meningitis hospitalization would remain stable in the pre- and post-Hib periods and in the 2010 bacterial surveillance and therefore could not have affected our findings. Lewis et al. reported that the proportion of patients with purulent CSF dropped from 18% in 2001-2002 to 8% in the 4th post-Hib vaccine year, and that during the same period the number of non-purulent cases remained constant (6). A recent 7-year period study in United States children's hospitals reported that the viral hospitalization rate declined minimally from 94% in 2005 to 91% in 2011 (29).

With the introduction in Yemen of pneumococcal vaccine in 2011, our study may provide important baseline data that may help in assessing the impact of the newly introduced vaccine. However, this needs an efficient surveillance system that includes more training on Gram staining and availability of latex agglutination and real-time polymerase chain reaction testing.

Conclusion

This study showed that in comparison with the pre-Hib period, the rates of all-cause meningitis hospitalization and death were significantly reduced in the post-Hib period. However, the rates ofvery severe pneumonia-related hospitalization and death were only modestly reduced, indicating that pneumonia is still the leading cause of severe morbidity and death for young children, particularly those under 12 months.

We also observed a significant reduction in CFR for all-cause meningitis and very severe pneumonia but not for gastroenteritis. In 2010, active bacterial meningitis surveillance recorded 22 cases with Strep. pneumoniae identified by Gram stain, which were equally distributed among vaccinated and unvac-cinated children. Only 1 case with H. nfluenzae was identified. Compared with the vaccinated children, unvaccinated children with suspected meningitis were 3.5 times more likely to have purulent CSF, and almost 4 times more likely to be treatment failures (death or permanent neurological complications). Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- The global burden of disease: 2004 update. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008 (http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GBD_report_2004update_full. pdf, accessed 26 February 2014).

- WHO position paper on Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccines. (Replaces WHO position paper on Hib vaccines previously published in the Weekly Epidemiological Record. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2006 Nov 24;81(47):445-52. PMID:17124755

- Global framework for immunization monitoring and surveillance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007 (WHO/ IVB/07.06).

- Adegbola RA, Secka O, Lahai G, Lloyd-Evans N, Njie A, Usen S, et al. Elimination of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) disease from The Gambia after the introduction of routine immunisation with a Hib conjugate vaccine: a prospective study. Lancet. 2005 Jul 9-15;366(9480):144-50. PMID:16005337

- Von Gottberg A, de Gouveia L, Madhi SA, du Plessis M, Quan V, Soma K, et al. Impact of conjugate Haemophilus influen-zae type b (Hib) vaccine introduction in South Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2006 Oct;84(10):811-8. PMID:17128361

- Lewis RF, Kisakye A, Gessner BD, Duku C, Odipio JB, Iriso R, et al. Action for child survival: elimination of Haemophilus influenzae type b meningitis in Uganda. Bull World Health Organ. 2008 Apr;86(4):292-301. PMID:18438518

- Braikat M, Barkia A, El Mdaghri N, Rainey JJ, Cohen AL, Teleb N. Vaccination with Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine reduces bacterial meningitis in Morocco. Vaccine. 2012 Mar 28;30(15):2594-9. PMID:22306854

- Lee EH, Corcino M, Moore A, Garib Z, Pena C, Sanchez J, et al. Impact of Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine on bacterial meningitis in the Dominican Republic. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2008 Sep;24(3):161-8. PMID:19115543

- Martin M, Casellas JM, Madhi SA, Urquhart TJ, Delport SD, Ferrero F, et al. Impact of haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine in South Africa and Argentina. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004 Sep;23(9):842-7. PMID:15361724

- Muganga N, Uwimana J, Fidele N, Gahimbare L, Gessner BD, Mueller JE, et al. Haemophilus influenzae type b conjugate vaccine impact against purulent meningitis in Rwanda. Vaccine. 2007 Sep 28;25(39-40):7001-5. PMID:17709159

- de Andrade AL, de Andrade JG, Martelli CM, e Silva SA, de Oliveira RM, Costa MS, et al. Effectiveness of Haemophilus influenzae b conjugate vaccine on childhood pneumonia: a case-control study in Brazil. Int J Epidemiol. 2004 Feb;33(1):173-81. PMID:15075166

- Baqui AH, El Arifeen S, Saha SK, Persson L, Zaman K, Gessner BD, et al. Effectiveness of Haemophilus influenzae type B conjugate vaccine on prevention of pneumonia and meningitis in Bangladeshi children: a case-control study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007 Jul;26(7):565-71. PMID:17596795'

- De la Hoz F, Higuera AB, Di Fabio JL, Luna M, Naranjo AG, de la Luz Valencia M, et al. Effectiveness of Haemophilus influen-zae type b vaccination against bacterial pneumonia in Colombia. Vaccine. 2004 Nov 15;23(1):36-42. PMID:15519705

- Theodoratou E, Johnson S, Jhass A, Madhi SA, Clark A, Boschi-Pinto C, et al. The effect of Haemophilus influenzae type b and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines on childhood pneumonia incidence, severe morbidity and mortality. Int J Epidemiol. 2010 Apr;39 Suppl 1:i172-85. PMID:20348119

- Lupisan SP, Ruutu P, Abucejo-Ladesma PE, Quiambao BP, Gozum L, Sombrero LT, et al.; Acute Respiratory Infections Vaccines (ARIVAC) Consortium. Central nervous system infection is an important cause of death in underfives hospitalised with World Health Organization (WHO) defined severe and very severe pneumonia. Vaccine. 2007 Mar 22;25(13):2437-44. PMID:17052818

- Laboratory methods for the diagnosis of meningitis caused by Neisseria meningitides, Streptococcus pneumonia, and Haemophilus influenza. WHO Manual, 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011 (WHO/IVB.11.09) (http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2011/WHO_IVB_11.09_eng.pdf, accessed 17 June 2014).

- West CP, Dupras DM. 5 ways statistics can fool you-tips for practicing clinicians. Vaccine. 2013 Mar 15;31(12):1550-2. PMID:23246309

- Asghar R, et al. Chloramphenicol versus ampicillin plus gentamicin for community acquired very severe pneumonia among children aged 2-59 months in low resource settings: multicentre randomised controlled trial (SPEAR study). BMJ. 2008;336:80-4. PMID:18182412

- Karambelkar GR et al. Disease pattern and bacteriology of childhood pneumonia in Western India. Int J Pharm Biomed Sci. 2012, 3:177-180.

- Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Walker N, Rizvi A, Campbell H, Rudan I, et al.; Lancet Diarrhoea and Pneumonia Interventions Study Group. Interventions to address deaths from childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea equitably: what works and at what cost? Lancet. 2013 Apr 20;381(9875):1417-29. PMID:23582723

- Rudan I, O'Brien KL, Nair H, Liu L, Theodoratou E, Qazi S, et al.; Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group (CHERG). Epidemiology and etiology of childhood pneumonia in 2010: estimates of incidence, severe morbidity, mortality, underlying risk factors and causative pathogens for 192 countries. J Glob Health. 2013 Jun;3(1):010401. PMID:23826505

- Cowgill KD, Ndiritu M, Nyiro J, Slack MP, Chiphatsi S, Ismail A, et al. Effectiveness of Haemophilus influenzae type b Conjugate vaccine introduction into routine childhood immunization in Kenya. JAMA. 2006 Aug 9;296(6):671-8. PMID:16896110

- Ayieko P, Okiro EA, Edwards T, Nyamai R, English M. Variations in mortality in children admitted with pneumonia to Kenyan hospitals. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e47622. PMID:23139752

- Brewster DR, Greenwood BM. Seasonal variation of paedia-tric diseases in The Gambia, west Africa. Ann Trop Paediatr. 1993;13(2):133-46. PMID:7687109

- Veirum JE, Biai S, Jakobsen M, Sandstrôm A, Hedegaard K, Kofoed PE, et al. Persisting high hospital and community childhood mortality in an urban setting in Guinea-Bissau. Acta Paediatr. 2007 Oct;96(10):1526-30. PMID:17850399

- Murray CJ, Lopez AD, Barofsky JT, Bryson-Cahn C, Lozano R. Estimating population cause-specific mortality fractions from in-hospital mortality: validation of a new method. PLoS Med. 2007 Nov 20;4(11):e326. PMID:18031195

- Youssef FG, El-Sakka H, Azab A, Eloun S, Chapman GD, Ismail T, et al. Etiology, antimicrobial susceptibility profiles, and mortality associated with bacterial meningitis among children in Egypt. Ann Epidemiol. 2004 Jan;14(1):44-8. PMID:14664779

- Wu HM, Cordeiro SM, Harcourt BH, Carvalho M, Azevedo J, Oliveira TQ, et al. Accuracy of real-time PCR, Gram stain and culture for Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis and Haemophilus influenzae meningitis diagnosis. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:26. PMID:23339355

- Nigrovic LE, Fine AM, Monuteaux MC, Shah SS, Neuman MI. Trends in the management of viral meningitis at United States children's hospitals. Pediatrics. 2013 Apr;131(4):670-6. PMID:23530164

Case management of childhood tuberculosis in children’s hospitals in Khartoum

T. Osman1 and A. EL Sony2

معالجة حالات سل الأطفال في مستشفيات الأطفال في الخرطوم

طارق عثمان، أسماء السني

الخلاصة: لا تتوافر معلومات منشورة حول معالجة حالات سل الأطفال في السودان. وتهدف هده الدراسة الأترابية إلى وصف معالجة حالات سل الأطفال في أربعة مستشفيات للاطفال في ولاية الخرطوم في السودان. وقد جمعت الييانات حول 467 طفلا تتراوح أعمارهم بين 0-14 عاماً تم تسجيلهم عام 2009، وذلك من سجلات المرضى ، وكان 52.9% منهم ذكوراً و53% منهم تتراوح أعمارهم بين 5-14 عاماً، وقد سجلت معظم الحالات على أنها حالات جديدة (89.5%)، معظمها سل رئوي (72.4%)، ومن بين جميع الحالات أجري الفحص المجهري للطاخات البلغم في 31% من الحالات. وكان لدى 35.8% منهم صور شعاعية، ولم يكن لدى أي واحد منهم سجل يفيد تأكيد التشخيص بالزرع. وقد أعطي النظام العلاجي من الفئة III لـ 58.5% منهم، وكان الإبلاغ عن النتائج بأنها شفيت (1.5%)، أو استكملت المعالجة (14.6%)، أو تم تحويلها (13.1%)، أو تخلفت (17.3%)، أو ماتت (4.3%)، أو فشلت المعالجة في (0.6%). ولوحظ ترابط يعتد به إحصائياً بين العمر وبين نتيجة المعالجة، أما الجتس ونمط المريض وموقع الآفة السلية وفئة المعالجة فلم يكن لحا اعتداد إحصائي. وتخلص الدراسة إلى أن معالجة حالات سل الأطفال في هده المنطقة لا ترقى إلى المستوى الأمثل.

ABSTRACT No published information is available on the case management of childhood tuberculosis (TB) in Sudan. The aim of this study was to describe the case management of childhood TB in 4 children's hospitals in Khartoum State, Sudan. Data on 467 children aged 0-14 years registered in 2009 were collected from patient records; 52.9% males and 53.0% aged 5-14 years. Most cases were registered as new cases (89.5%) and most had pulmonary TB (72.4%). Of all cases, 31.0% had sputum smear microscopy done, 35.8% had X-ray and none had a record of being culture confirmed. Category III regimen was given to 58.5%. Reported outcomes were: cured (1.5%), completed treatment (14.6%), transferred out (13.1%), default (17.3%), death (4.3%) and treatment failure (0.6%). Age was significantly associated with treatment outcome, while sex, type of patient, site of TB and treatment category were not significant. Case management of childhood TB is suboptimal in this region.

Prise en charge des cas de tuberculose chez l'enfant à l'hôpital pour enfants de Khartoum

RÉSUMÉ Il n'y a pas d'informations publiées sur la prise en charge de la tuberculose chez l'enfant au Soudan. L'objectif de la présente étude était de décrire la prise en charge de la tuberculose chez l'enfant dans quatre hôpitaux pour enfants de l'État de Khartoum (Soudan). Les données de 467 enfants âgés de 0 à 14 ans enregistrées en 2009 ont été recueillies à partir de leurs dossiers médicaux ; 52,9 % étaient des garçons et 53,0 % étaient âgés de 5 à 14 ans. La plupart des cas étaient enregistrés comme des nouveaux cas (89,5 %) et la majorité était atteinte de tuberculose pulmonaire (72,4 %). Sur l'ensemble des cas étudiés, 31,0 % avaient fait l'objet d'examens microscopiques de frottis d'expectoration, 35,8 % avaient été soumis une radiographie mais aucun cas n'avait été confirmé par culture en laboratoire. Un traitement de catégorie III a été administré à 58,5 % d'entre eux. Les résultats recueillis étaient les suivants : guérison (1,5 %), traitement achevé (14,6 %), réorientation (13,1 %), abandon du traitement (17,3 %), décès (4,3 %) et échec du traitement (0,6 %). L'âge était significativement associé à l'issue du traitement, tandis que le sexe, le type de patient, le site de la tuberculose et la catégorie du traitement ne l'étaient pas. La prise en charge de la tuberculose chez l'enfant n'est pas optimale dans cette région.

1Sudan MedicaL and Scientific Research Institute, University of Medical Sciences and Technology, Khartoum, Sudan (Correspondence to T. Osman:

2EpidemioLogicaL Laboratory, Khartoum, Sudan.

Received: 28/07/13; accepted: 04/03/14

EMHJ, 2014, 20(7): 442-449

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) kills more youths and adults than any other single infectious disease in the world (l). It is estimated that in 2010 there were 8.8 million incident cases, 12 million prevalent cases and 1.4 million deaths from TB. The greatest burden of disease is in Asia and Africa. Africa is the most affected region, with dual TB/HIV infection comprising 82% of the 1.1 million cases of TB (2).

TB is an important cause ofmorbid-ity and mortality in children (3). There are approximately 1 million cases of childhood TB annually (4). Estimates of disease burden suggest that children account for 11% of TB cases globally (5,6). However, the proportion of TB cases that occur in children is highly variable across different countries and may reach 40% in sub-Saharan Africa (4-8). The global burden ofTB in children and its impact on the health of children are being increasingly recognized (9). In developing countries, TB is responsible for 10% of childhood hospital admissions and 10% of hospital deaths (5). Globally, it continues to exact a high toll of disease and death among children, particularly in the wake of the HIV epidemic (6).

Sudan bears 15% of the TB burden in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (10), and despite some improvements is lagging behind in progress towards achieving the Millennium Development Goals (ll). In 2010 the case detection rate was 50%. In 2009, 62% of cases were cured, 19% completed treatment, 3% died, 1% failed treatment, 10% defaulted and 6% were not evaluated. A best estimate for the number of HIV-positive incident TB cases in the country is 7100 (2).

The strategy of the National TB Programme (NTP) in Sudan is screening of children who are contacts through tuberculin skin testing and chest X-ray or on the basis of clinical assessment if these tests are not available. Children not found to have TB receive isoniazid preventive therapy. Children found to have TB undergo the full routine diagnostic procedures (history, chest X-ray, bacteriological confirmation of specimens by microscopy, culture and histopathology), treatment (according to diagnostic category), recording and reporting (12).

There are no published articles on the clinical characteristics, case management and treatment outcomes for childhood TB in Sudan. In Sudan, a low case detection rate, a high prevalence of adult TB cases, pervasive poverty, poor TB treatment outcomes, rampant childhood malnutrition and diagnostic challenges for case ascertainment all provide a setting for suboptimal childhood TB management. The purpose of this cohort review was to describe the characteristics, treatment outcomes and case management of childhood TB in the setting of children's hospitals in Khartoum.

Methods

Design and setting

This was a retrospective cohort review of 467 children aged 0-14 years who were registered as TB cases and received treatment from January to December 2009. All records of childhood TB cases during this period were reviewed. The guidelines for management of childhood TB in Sudan were changed in 2010. However, since the cohort of 2010 was not complete by the start of the study, a decision was made to review the cohort study for 2009. The cohort for 2009 was managed according to the 2006 guidelines of the National manual for the management of childhood tuberculosis in Sudan (12). The 2006 manual provides diagnostic and management guidelines that follow the guidelines outlined in the World Health Organization's (WHO) Guidance for national tuberculosis programmes on the management of tuberculosis in children (13).

Children with TB are diagnosed and registered for treatment at children's hospitals in Sudan. The TB register and follow-up treatment cards are supervised by the paediatricians and coordinators of the NTP management units at these hospitals. Treatment cards contain patient demographics, TB clinical characteristics and follow-up progress on management. The study was conducted at 4 tertiary care children's hospitals (Jaafar Ibn Ouf Children's Hospital, Omdurman Children's Hospital, Ahmed Gasim Children's Hospital and Elbuluk Children's Hospital) in Khartoum State, Sudan.

Data collection and analysis

The data sources were the TB registry and treatment cards. The primary variables ofinterest as defined by the national guidelines were: type of patient, site of TB, category of regimen and treatment outcome. The secondary variables of interest were: age, sex, type of investigations (chest X-ray, smear microscopy, culture), pretreatment weight measurement, HIV counselling, HIV testing and HIV status.

The data were recorded in a specially designed, structured questionnaire. All inconsistencies were resolved by referring to the records. Where no patient data for the variable were recorded in the data sources, it was classified as unknown.

Definitions

The definitions used were in line with similar studies and standard WHO definitions (13).

- New case: TB patient who has never had treatment for TB or has taken anti-TB drugs for < 1 month.

- Relapsed: TB patient who had been declared cured or whose treatment had been completed by a physician, but who reports back to the health service and is now found to be sputum smear-positive.

- Transferred in: TB patient who has been received for treatment into a TB unit after starting treatment in another unit where s/he had been registered).

- Treatment after default: TB patient who has received anti-TB treatment for at least 1 month from any source and has returned to treatment after having defaulted.

- Other: TB patient who does not fit into the above-mentioned types.

- Cured: TB patient who is sputum smear-negative in the last month of treatment and on at least 1 previous occasion.

- Completed treatment: TB patient who has completed treatment but who does not meet the criteria to be classified as cured or treatment failure.

- Default: TB patient whose treatment was interrupted for 2 consecutive months or more.

- Died: TB patient who dies for any reason during the course of treatment.

- Treatment failure: TB patient who is sputum smear positive at 5 months or later after starting treatment.

- Transferred out: TB patient who has been transferred to another recording and reporting unit and for whom the treatment outcome is not known.

Ethical considerations

The protocol was reviewed and granted clearance by the ethics committee of the Khartoum State Ministry of Health and the NTP Coordinator of Khartoum State. Final consent was obtained from the directors of the 4 hospitals to access the data archives. Consent was not required from parents as this study involved a review of records.

Data analysis

The data were analysed using SPSS for Windows, version 16. Basic descriptive analysis and calculation of proportions were performed. Chi-squared tests and Fisher exact test were performed for comparison of categorical data. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. The statistical power of the study was 95%.

Results

Characteristics of children with TB

Age and sex characteristics

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of children with TB. Of the 467 cases registered and receiving treatment at the children's hospitals, 247 (52.9%) were males and 220 (47.1%) were females. The M:F ratio was 1.2:1. There were fewer children in the 0-4 year age category (46.7%) than in the 5-14 years age category (52.7%); 3 children did not have their age recorded. The median age was 60 months [interquartile range (IQR) 24-108 months].

Childhood TB characteristics

Most cases (418, 89.5%) were new, 5 children (1.1%) were classified as relapsed cases, 13 (2.8%) as transferred-in, 9 (1.9%) as treated after default and 1 (0.2%) was classified as other; in 21 cases (4.5%) the type of patient was unknown. There were more pulmonary TB (72.4%) than extrapulmonary TB cases (27.4%); in 1 case (0.2%) the site of TB was not recorded. Ofthe children 9.2% had smear-positive pulmonary TB and 26.0% had smear-negative pulmonary TB; in 64.8% of children the smear status of pulmonary TB was unknown. The specific types ofextrapulmonary TB were not recorded. Radiography results were positive in 30.0%, negative in 5.8% and unknown for 64.2% of children. None ofthe cases had any record of culture being done. Pretreatment weight measurement was taken for 61.0% of children, but was unknown for 39.0%. Category III and category I regimens were given to 58.5% and 36.4% of cases respectively; there was no record of the treatment category for 1.9%. A total of 42.8% cases had received the treatment regimen for their disease category, but 7.3% did not receive the recommended regimen. In 49.9% of children it could not be determined whether the correct category of regimen was administered. The median duration of treatment was 223 days (IQR: 202-241 days).

Treatment outcomes

Information on treatment outcome was available for 240 (51.4%) cases. Overall 16.1% had a favourable treatment outcome; 1.5% were cured and 14.6% completed treatment. The unfavourable treatment outcomes were: default (17.3%), death (4.3%) and treatment failure (0.6%). There were 13.1% of cases recorded as transferred out. The duration of treatment was defined for 48 children (64.0%) with a favourable outcome.

TB/HIV

HIV counselling was provided to 24 (5.1%) of the cohort. A total of 57 children (12.2%) had had an HIV test and only 2 (0.4%) were HIV positive; both were males, were from both age groups, were new cases, had smear-negative pulmonary TB, received category III regimen and had no record of receiving counselling, anti-retroviral therapy (ART) or co-trimoxazole preventive therapy. One defaulted and the other was transferred out.

Association between children's characteristics and treatment outcomes

Table 2 shows the association between the outcome of treatment and sex, age, type ofpatient, site of TB and treatment category. Considering the treatment outcomes and whether they were favourable or unfavourable, the associations between treatment outcome with sex, type of patient, site of TB and treatment category were all non-significant (P = 0.891, P = 0.306, P = 0.108 and P = 0.298 respectively). However, significantly more cases in the 5-14 year age group had favourable outcomes (52.7% versus 47.3%, P = 0.002).

Discussion

This was the first hospital-based study to review the characteristics, treatment outcomes and case management of childhood TB in children's hospitals in Sudan. It was a review of management from patients' records. It is critical to evaluate adherence to NTP policies for childhood TB management and the effectiveness of the management of childhood TB by hospital paediatricians. The study highlights pertinent points for the review of childhood TB management in children's hospitals.

For comparisons with other studies we searched the literature with a primary focus on research from Africa. We used the following search terms: childhood TB, paediatric TB, paediatric TB, standard case management, case management, treatment outcomes, characteristics, investigations, diagnosis, developing countries, Africa, Asia and Eastern Mediterranean Region to construct search strategies. We searched PubMed, HINARI, WHO website and Google Scholar to identify the freely available, scholarly and scientific references on the subject matter. The oldest reference was from 2002.

Reporting and recording

Children registered and managed in children's hospitals should have complete TB registers and treatment cards. Five key elements of childhood TB standard case management allow for valid assessment of the quality of case management. These are: pretreatment weight measurement, type of patient, site of TB, treatment category and treatment outcome. In this cohort, recording and reporting of type of patient, site of TB and category of treatment regimen were adequate but there were inadequacies in reporting of pretreat-ment weight measurement, investigations, type of pulmonary TB and treatment outcomes. The recording and reporting system identifies patients who are failing therapy (14). Inadequacies in recording and reporting have been reported elsewhere, particularly with regards to treatment outcomes (15,16). Inadequate reporting of weight raises ethical concerns. For example, children in Malawi receiving anti-TB treatment were reported to have had inappropriate and low drug dosages (8). Weight is an indicator for response to treatment. Pretreatment weight measurement is important and should be common practice in Sudan, where childhood malnutrition is rampant. The outcome of TB treatment in children is frequently not reported. The highest reported rate for not reporting treatment outcome was 87% in Pakistan (17). This may reflect unfamiliarity with the recording and reporting process, lack of training or poor follow-up by treatment providers, or poor level of commitment by practitioners, workload and limited experience (17).