Qualitative adaptation of child behaviour problem instruments in a developing-country setting

B. Khan1 and B.I. Avan2

المواءمة الكيفية لأدوات قياس مشكلات السلوك لدى الأطفال في مواقع البلدان النامية

بشرى خان، بلال إقبال أعوان

الخلاصة: إن أحد العوائق الرئيسية للبحوث الوبائية حول مشكلات السلوك لدى الأطفال في البلدان النامية هو فقدان أدوات ملائمة ثقافياً ومعترف بها دولياً لقياس السلوك. وتقزح هذه الورقة نمودجاً للمواءمة الكيفية لأدوات القياس النفسي في مواقع البلدان النامية، مع تقديم دراسة حالة لمواءمة ثلاث أدوات معترف بها دوليا في باكستان، وهي: القائمة التفقدية لسلوك الأطفال، والإبلاغ الذاتي للشباب، واستمارة تقرير المعلم. ويتضمن هذا النموذج إجراءات منهجية ذات ست مراحل متمايزة تستهدف الإقلال من التحيز وضمان التكافؤ لأقصى قدر ممكن مع الأدوات الأصلية من حيث: الاختيار، والمداولات، والتغيير، وإمكانية التطبيق، والارتياد، والموافقة الرسمية. وقد تم تنفيذ العملية بالتعاون مع القائمين على إعداد الأداة، إذ حدد فريق عمل يتكون من الخبراء المتعددي التخصصات قضايا التكافؤ والتعديلات المقترحة. كما أوضحت مناقشات المجموعات البؤرية للمستجيبين للدراسة قضايا ذات أهمية استيعابية؛ ثم تلا ذلك تجريب الأدوات المعدلة تجريبا ارتيادا، وأخيرا تحقق مطور الأداة من الحصول على الموافقة عل المواءمة الكيفية. وتقترح الدراسة نموذجاً صارماً ومنهجياً لتحقيق المواءمة الثقافية لأدوات القياس النفسي بنجاح.

ABSTRACT A key barrier to epidemiological research on child behaviour problems in developing countries is the lack of culturally relevant, internationally recognized psychometric instruments. This paper proposes a model for the qualitative adaptation of psychometric instruments in developing-country settings and presents a case study of the adaptation of 3 internationally recognized instruments in Pakistan: the Child Behavior Checklist, the Youth Self-Report and the Teacher's Report Form. This model encompassed a systematic procedure with 6 distinct phases to minimize bias and ensure equivalence with the original instruments: selection, deliberation, alteration, feasibility, testing and formal approval. The process was conducted in collaboration with the instruments' developer. A multidisciplinary working group of experts identified equivalence issues and suggested modifications. Focus group discussions with informants highlighted comprehension issues. Subsequently modified instruments were thoroughly tested. Finally, the instruments' developer approval further validated the qualitative adaptation. The study proposes a rigorous and systematic model to effectively achieve cultural adaptation of psychometric instruments.

Adaptation qualitative des instruments mesurant les problèmes comportementaux chez l'enfant dans un contexte de pays en développement

RÉSUMÉ Le manque d'instruments psychométriques internationalement reconnus et culturellement adaptés représente un obstacle majeur à la recherche épidémiologique sur les problèmes comportementaux chez l'enfant dans les pays en développement. Le présent article propose un modèle pour l'adaptation qualitative d'instruments psychométriques au contexte des pays en développement et présente une étude de cas sur l'adaptation au Pakistan de trois instruments internationalement reconnus : la liste de contrôle du comportement des enfants (Child Behavior Checklist), l'auto-évaluation des jeunes (Youth Self-Report) et le rapport d'évaluation de l'enseignant (Teacher's Report Form). Le modèle comprenait une méthode systhématique en six phases distinctes visant à réduire au minimum les biais et à garantir l'équivalence avec les instruments originaux : sélection, délibération, modification, faisabilité, test et approbation formelle. La méthode a été utilisée en collaboration avec le concepteur des instruments. Un groupe de travail pluridisciplinaire composé d'experts a identifié les problèmes d'équivalence puis a suggéré des modifications. Des discussions entre les groupes thématiques et les informateurs ont permis de mettre en évidence les problèmes de compréhension. Les instruments modifiés ont ultérieurement été entièrement testés. Enfin, l'approbation du concepteur des instruments a aussi permis de valider l'adaptation qualitative. L'étude propose un modèle rigoureux et complet permettant d'obtenir une adaptation culturelle efficace des instruments psychométriques.

1Department of Psychology, University of Karachi, Karachi, Pakistan (Correspondence to B. Khan:

Received: 25/08/13; accepted: 23/03/14

Introduction

Behaviour and emotional problems in children are becoming a globally important public health issue (1-3). Behaviour problems have long-term detrimental consequences (4-7); early detection of problems, followed by evidence-based interventions, is vital for their prevention (l). Epidemiological studies show that the prevalence of childhood behaviour problems varies cross-culturally, although most of this evidence comes from developed countries (8-14). The key barrier to collecting empirical evidence in developing countries is the unavailability of culturally and scientifically adapted instruments (15) to measure the burden of problems and to track the effectiveness of interventions. The aim of adaptation is to make an instrument relevant to a culture that is different from the one for which it was originally developed. It limits any partiality and unfairness of the tool with a particular focus on construct bias, i.e. when concepts differ cross-culturally; on method bias, i.e. when ways to assess construct are unfamiliar to people; and on item bias, i.e. when translation of items is either poor or ambiguous or may not be culturally acceptable (16).

Adaptation is primarily achieved by 2 processes: statistical, which employs quantitative procedures, and operative, which is a qualitative judgemental process that focuses on how and what kinds of adaptations have been done to ensure methodological equivalence with the original version of the instrument (17). The definitions which Flaherty et al. suggested (18) are outlined in Tablel. Both qualitative and quantitative processes of adaptation are important and have their distinct methods of validation and ensuring scientific soundness. However, qualitative process takes precedence in adaptation of an instrument to a new culture or setting.

The adaptation of psychometric instruments to developing country settings is particularly challenging due to the lack of suitable experts in the subject (19,20) and the general reluctance ofthe community to participate in research. There has been little research done to highlight such challenges and to suggest an adaptation procedure for developing countries, especially concerning instruments related to child behaviour. This paper explains a systematic process of qualitative adaptation of 3 parallel, multi-informant child behaviour problems instruments in a developing country, Pakistan, aiming to highlight the challenges faced during this process and to propose a logical model to attain a qualitative adaptation of psychometric instruments.

Methods

Measures

The tools selected for qualitative adaptation were the Achenbach System ofEm-pirically Based Assessment (ASEBA) school-age instruments (21), i.e. the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) for ages 6-18 years and its related parallel instruments; the Teacher's Report Form (TRF) for ages 6-18 years; and the Youth Self-Report (YSR) for ages 11-18 years. These instruments were originally developed in the United States ofAmerica (USA) and are widely used to measure child behaviour problems and are often considered as the gold standard for research and clinical work (22). They have been translated into more than 85 languages for use in developed and developing countries and have been used in more than 7000 international studies (23). They provide an assessment of a child's problems from different informants in different settings.

The YSR is a self-reported instrument for children to report their emotional and behaviour problems (105 problem items and 14 social desirability items) and competencies (20 items). The CBCL is for a caregiver to provide information about the child's competence (20 items) and problem behaviour (120 items). The TRF is a teacher-reported instrument with items related to academic and adaptive functioning in addition to 120 problem items. The competence items in CBCL and YSR provide information about a child's activities, social interactions and school performance, while problem items reflect the child's behaviour and emotional problems and are measured on a 3-point rating scale.

Study setting and participants

The adaptation process was carried out in Karachi, an urban cosmopolitan city of Pakistan, with a population representing all parts of the country. The study data were collected through focus group discussions (FGDs) and final testing out. The study was done in collaboration with the local Teachers' Resource Centre. This is a teachers' professional capacity-building organization which has a huge network of member schools in Karachi, primarily private schools serving pupils of all socioeconomic levels, and was willing to be part of future studies or interventions based on the adapted instruments.

The Centre invited all co-education member schools that had both primary and secondary education curricula to participate in the study. Co-education was operationally defined as those schools in which male and female children study in the same classroom. The reason for including only coeducation schools was that the future empirical studies based on the adapted instruments could be compared cross-culturally where schools provide equal opportunities to male and female children to study. Five schools showed an interest in participating in the study, but considering the qualitative nature of the study 2 schools were randomly selected for the FGDs, i.e. 1 school for the each of the 2 rounds of FGDs, and the rest of the schools were selected for the 2nd round of testing.

Participants (i.e. the informants of the study) were purposefully selected and comprised schoolchildren aged 11-18 years studying in grades 6 to 10 and mothers and female teachers of children aged 6-18 years. The decision to involve mothers participating in school-related activities rather than fathers was based on discussion with the Teachers' Resource Centre representatives and heads of member schools. The reason for inclusion of female teachers in the study was that most of the teachers in the education system of Pakistan, especially in school settings, are females.

Study context

The adaptation of the CBCL and related instruments was done primarily for a large-scale epidemiological study on behaviour problems among children in Karachi, Pakistan between the years 2009 to 2010. This study was approved by the ethics review committee of Bridge Consultants Foundation, Pakistan, which is registered with the Office of Human Research Protection of the National Institutes of Health in the USA.

Ethical considerations

Informed consent to collect data from children, teachers and parents was received from schools after explaining the study's aim, objectives, procedures and instruments. Children and teachers were also informed about the study at the time of the data collection and although they were free to decide about participation they were encouraged to participate in the study by the school personnel. Formal invitation letters including information about the study and consent forms were sent to parents via schools. Parents who gave their consent were included in the study.

Procedure

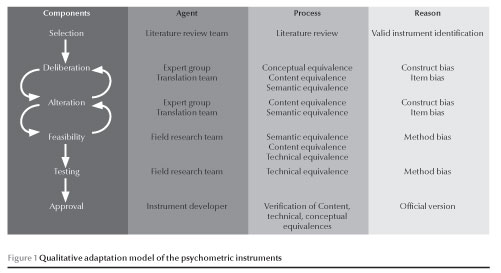

The process of qualitative adaptation of the CBCL and related instruments was achieved through 6 discrete, sequential and iterative phases (Figure 1).

Phase I: Selection phase

The focus in phase I was on the selection of an appropriate instrument and developing a working group of multidisciplinary experts to ensure its cultural appropriateness. The authors selected the ASEBA instruments from all the leading instruments on the basis of their comprehensiveness in catering for a range of behaviour problems, their soundness in methodology used for their development and the evidence of their use in wider contexts (24,25). Contact with the instruments' developer revealed the existence of Urdu translated versions needing systematic updates. Thus a collaborative, qualitative adaptation plan was mapped out. To form a working group, key national organizations were contacted to nominate 1 senior member from their respective departments. The final group comprised 6 multidisciplinary experts from the disciplines ofchild psychology, public health, epidemiology, education and bilingual linguistics in Urdu and English

Phases II, III & IV: Deliberation, alteration and feasibility-iterative processes

In the following phases the working group started deliberating on the suitability of the instruments in the Pakistani culture, determining the need for modifications in the provisional Urdu translations and moving on to alterations by suggesting suitable modifications. The working group also endorsed the selection of the ASEBA instruments and re-affirmed that those instruments could be compared cross-culturally. Finally, the feasibility of the modified instruments was checked with informants and the whole cycle was revised to eliminate non-feasible items.

The adaptation process also included a translation team and a field research team. The multidisciplinary translators were primarily involved in the alteration phase for forward and backward translation of the instruments but were also part of the final deliberation and iteration with the working group. The field research team was involved in checking the feasibility of the instruments in FGDs with informants and conducting a final test. Many rounds of meetings and FGDs followed as described below.

1st meeting with working group: To

ascertain the cultural suitability of the instruments, the original version ofeach instrument was shared with experts and a consensus was reached about the necessary adaptation. All working group members were given a copy of the original English version and provisional translation of all 3 instruments (YSR, CBCL and TRF) and a working grid to specify agreement/disagreement about correctness of translations and suggestions for modifications, together with the reasons. Discussions were focused on determining cultural appropriateness and the equivalence of instrument items, including instructions for their administration, using dictionaries and thesauruses where necessary. All meetings were facilitated by the investigator and recorded by an observer.

1st round of FGDs with informants:

FGDs were organized in 1 of the 2 schools randomly selected for FGDs and were conducted by a trained facilitator who was a clinical psychologist and had extensive experience and expertise in conducting and analysing FGDs with children and adults. The facilitator conducted 3 separate FGDs with male and female children aged 11-18 years, mothers of children aged 6-18 years and female teachers of children aged

6- 18 years. The age range of mothers was 25-45 years and of teachers was 25-35 years. Each session included 7- 8 participants who were purposefully selected. Through cognitive interviews all items and instructions of the provisionally translated instruments were discussed. Comprehension and cultural relevance were checked through explanation of items in their own words. We discussed all items one by one. For comprehension, participants were asked to describe and explain the item, i.e. they were asked to say that what they thought that item was about/saying or to repeat it in their own words that would reflect their interpretation of the item. They were also asked if there was any word in the item which they were not able to understand. For cultural relevance, they were asked if they were satisfied with the existing expression or would like to suggest any other easy and commonly used word/expression. Also they were asked if words/items were acceptable or offensive to them.

2nd meeting with working group: Observations and suggestions from the 1st round of FGDs were shared with the working group and this led to a consensus firstly to modify the instruments to make them equivalent to the original English versions and secondly to recheck these with informants.

2nd round of FGDs with informants:

The 2nd round of FGDs were carried out in another school and a new group of informants was purposefully selected, i.e. male and female children aged 11-18 years and mothers and female teachers of children aged 6-18 years. The age range of mothers was 25-40 years while teachers were aged 30-40 years. Provisional translations including suggested modifications were discussed. Suggestions for cultural adaptation of the examples in the instruments were also noted. The facilitator who conducted the first round of FGDs facilitated the second round as well.

Based on the above procedure 3 detailed documents for the YSR, CBCL and TRF respectively were produced indicating each item number, provisional translation, suggested modifications in translation and reason for modification. Documents with details of procedures were shared with the developer and a formal licence was received for updating the translations.

Forward translation of instruments:

Three bilingual English-Urdu translators, with backgrounds in psychology, public health and linguistics respectively, translated the instruments as a group, keeping in mind all suggestions from the working group and FGDs. They ensured conceptual equivalence (translating the same concept), semantic equivalence (identifying appropriate words), content equivalence (ensuring item relevance) and technical equivalence (ensuring syntax, grammar, layout and format of the original English version).

Back translation: All the translated instruments were then back translated to English by an independent bilingual linguist who was blind to the original English instruments.

Final review by the working group: All

the original, translated and back translated instruments were then shared with the working group for their feedback and agreement to initiate testing.

Phases V and VI: Testing and approval

Testing and finalization of instruments: The adapted instruments were finally tested on 100 male and female children aged 6-18 years. Of them, for 70 male and female children aged 11-18 years the informants were the children themselves, their mothers and their 6 teachers, whereas for 30 male and female children aged 6-10 years, their mothers and 3 teachers were the informants. The age range of mothers was 25-45 years and of teachers was 25-40 years.

Testing was carried out in the randomly selected 3 schools of the Teachers' Resource Centre. The participants were instructed by the field research team to complete the instruments. Immediately after the participants handed over the complete instruments to the team they were asked questions regarding the comprehension of instructions, meaning of items, ease of language, cultural relevance and ease with format and layout. The field research team that conducted the testing comprised 6 members with master's degrees in psychology and education with prior research experience of working with children and adults in communities. The field team was provided with training in interview and communication skills before data collection. Out of 6 members of the team 3 conducted the testing with children, 2 with mothers and 1 with teachers.

Approval

During testing, the field research team identified a few ambiguities in the adapted instruments, which were then corrected and incorporated by the investigators into the instruments after the testing. Final translations and back translations of adapted instruments were then shared with the instruments' developer in order to obtain approval as an official version of ASEBA.

Results

Phase 1: Selection

Child behaviour problems have been assessed through various approaches, but rating scales are the most commonly used assessment approach in epidemiological research and interventions (26) because of their standardized format for assessing, scoring and interpreting behaviour (25). The rating scales include general-purpose instruments assessing all type of behaviour problems in the general population (25) and those measuring specific problems such as depression (27). Although there are other general-purpose instruments to measure child behaviour problems (28-30), the ASEBA tools were chosen by our panel because of their comprehensiveness in assessing child behaviour problems, the sound methodology of their development and established international reputation for epidemiological studies.

Phase II-IV: Deliberation, alteration and feasibility

1st meeting with working group

Besides checking the instruments for equivalence with the original English versions the working group also identified numerous typing errors and use of Persian and Arabic origin words in the provisional translations. Some examples of modifications suggested by the working group for equivalence were as follows:

- Conceptual equivalence: YSR problem item 15 "I am pretty honest" was incorrectly translated as main aksar sach bolta hon ("I often speak truth"). However, the appropriate and literal translation of "honest" could be im-aandaar, because speaking truth is part ofhonesty (imaandari), as in other attributes such as trustworthiness and conscientious. In the same item "pretty" was also incorrectly translated as aksar ("often"); the correct translation of "pretty" is kaafi.

- Content equivalence: CBCL problem item 11 "clings to adults" was not translated in the provisional Urdu version. The translation could be ba-roon se chipkta/chipakte hai. This addition was important to make the item more comprehensible.

- Semantic equivalence: CBCL problem item 8 "for long" was translated as taweel arse kay liye, in which taweel is an Arabic origin word and taweel arse generally refers to years. Ziyada dair tak gives the exact meaning ofthe English expression and is also commonly used.

- Technical equivalence: TRF item 24 "pupils" was translated as talaba which is the plural oftalib e ilm ("male student"). In English language the plural is used for both male and female students, whereas in Urdu, tali-baat, the plural of taliba, is used for female students. Therefore it was suggested that talaba or talibaat be used instead ofmentioning only talaba.

1st round of FGDs with informants

FGDs with children, mothers and teachers highlighted numerous items and instructions which were either difficult to understand or misunderstood. Some examples are given as follows:

- Semantic equivalence: YSR problem item 13 "confusion" was translated as tazabzub, which is a very difficult word for children to understand because it is an uncommon Arabic origin word. However, uljhan, a synonym of taza-bzub, is widely used and understood.

- Semantic equivalence: TRF problem item 86 "irritable" was translated as tunak mizaaj, which is a difficult word for teachers as it is an uncommon Persian-origin word, whereas chirchi-ra is a synonym of tunuk mizaaj and is very easy to understand.

- Technical equivalence: unnecessary grammatical changes in items caused some offence to participants; for example, CBCL problem item 43 "lying and cheating" was translated as liar and cheater, wo jhota/jhoti aur dho-kaybaz hai.

- Content equivalence: participants suggested add a few more culturally relevant examples such as sports like cricket, hockey and football in CBCL and YSR competence item 1 and also suggested deleting fishing as it is not a common local sport.

- Technical equivalence: all participants were confused about the instructions for the problem items. "True" was translated as sach ("truth") and they were confused that if they marked that a certain behaviour never happened, it would it be considered as lying.

Participants also suggested retaining items related to sex and alcohol in spite of the cultural taboos concerning these.

2nd meeting with working group

This meeting revealed and discussed issues arising in translation with respect to misunderstandings and use of potentially offensive and morally connotated words in items. The working group endorsed the informants' suggestions and agreed to modify offensive translations while maintaining the equivalence with the original items. Some examples are as follows:

- After suggestions from informants to add the name of local sports in YSR and CBCL competence item 1 it was decided to include them with the ones mentioned in the original English version and to recheck it in the 2nd round of FGDs.

- Misinterpretation of instruction and response categories of the problem items in the CBCL, YSR and TRF was identified as due to the translation of "true" to sach, which means "truth", and "not true" as sach nahin, which means "lie". This seemed to have a moral connotation to respondents. However, the purpose of the items in the instruments was to determine whether a certain behaviour is relevant to the child and the extent of its applicability. Therefore translating "true" as sach would be inappropriate, while the suggested translation sahi seemed appropriate as it could enable the informant to see the applicability of the items by agreeing, disagreeing or somewhat agreeing without invoking the moral implications of being "truthful".

The working group also endorsed retaining items pertaining to sex and alcohol.

2nd round of FGDs with informants

In the 2nd round of FGDs the new groups of informants endorsed the modified translations and the retention of culturally relevant examples.

Forward translation of instruments

During translation, the primary focus was on semantic equivalence while incorporating inputs from the working group and FGDs regarding other types of equivalence as well. It was ensured that layout, format, item placement, sequence and scoring patterns were equivalent. Items were translated in functional and simple language to suit the requirement of self-report instruments. It was ensured that items were used with supportive expressions that made them useable for both sexes, as required in Urdu language.

Final review from the working group

The working group reviewed and discussed the translations and back translations with the original English version with the translators and approved them for final testing.

Phase V: Testing

During testing, informants found the adapted instruments relevant and understandable but a few typing errors were identified that were corrected and incorporated in the instruments after the testing.

Phase VI: Approval

Final translation and back translation of instruments were then shared with the instruments' developer who checked back translations with the original English version of the instruments to ensure equivalence. He further confirmed the equivalence ofadapted instruments and also highlighted an important point by suggesting replacing English as an academic subject with Urdu in CBCL and YSR item VII-1, assuming that English might not be taught in Pakistan. However, we finally included Urdu along with English with the rationale that in Pakistan we have Urdu and English language schools so children belonging to both type ofeducation systems could easily relate to it.

Discussion

Qualitative adaptation is a systematic and rigorous process as compared with a simple translation of a psychometric instrument, especially in the context of a developing country. But, once achieved, the process ensures the quality of research findings as compared with more compromised adaptations (31,32). Since there is no consensus on the best practice to be employed for qualitative adaptation (17), we attempted a systematic approach to satisfy multiple equivalence needs of an adapted version of the child behaviour problem instruments and proposed a model of qualitative adaptation of psychometric instruments for developing countries (Figure 1). The process of qualitative adaptation comprised 6 phases and employed many arduous iterations until the instruments were technically equivalent to the original English versions, with minimal potential biases. There follows a brief account of the key logistic and other challenges faced during the adaptation process.

Language is a complex social phenomenon whose content and structure is continually evolving through historical, cultural and socioeconomic influences. Vocabulary expansion in languages sometimes borrows words from multiple other linguistic sources; consequently a choice of words sometimes exist even for the same experience. The selection of the specific word depends on the sociocultural background of the user or listener in order to capture the specific nuance in the communication. This understanding is particularly important for the qualitative adaptation of a psychometric instrument. The Urdu language vocabulary contains a range of words borrowed from native languages such as Punjabi, Pashto and Sindhi and regional languages such as Arabic, Persian Sanskrit and Turkish. Its translational vocabulary and syntactical structure changes with the sophistication oflanguage use. Various alternatives are available for the same concept and therefore choice of words requires careful deliberation. One of the key challenges of this project was to come up with a translation that achieved uniform comprehension across all social classes.

The other technical challenge was synchronization of multi-informant instruments that had common items. Multi-informant instruments obtain the views of different informants about the same child's behaviour. During adaptation, using the YSR as the reference, it was necessary to ensure that translations of common items and terminologies be consistent across all the instruments, as all informants would be reporting about the same child and therefore interpretation of such items should be consistent. After extensive discussions with informants, words were obtained that were commonly understandable and equivalent with the original English versions.

Consistent with studies conducted to adapt various instruments in developing countries (33,34), another challenge was to ensure all types of equivalences—semantic, conceptual, content and technical—with the original English version. For semantic equivalence, the fact that these instruments were to be completed via self-reporting meant that we needed to identify commonly used words so that informants would not need further clarification. Conceptual and content equivalences were ensured by critical discussion ofall items with the working group and FGD informants. However, some changes were made by adding culturally relevant examples to facilitate understanding. After careful exploration in FGDs, testing and discussions with the working group, we decided to retain those items related to sex and alcohol. The logic for this was that it would not be a good idea to assume that these were not culturally relevant (due to low frequency or under-reporting) or exclude any problem item, especially when such problems do exist even in a conservative society like Pakistan. To ensure technical equivalence, we checked if informants were comfortable with the format of item presentation, response categories and instructions.

Developing a working group of experts (35) who were working from a public health perspective with relevant experience and expertise was an uphill task. As there is a general scarcity of mental health experts in developing countries (36,37) very few people are working exclusively in the area of child behaviour and even fewer had practical research experience. Moreover, a majority of the experts work normally in isolation in their respective fields. However, formation of multidisciplinary groups with experience in psychology- and public health-related initiatives played a key role in devising a better adapted instrument.

The qualitative adaptation phases containing cycles of deliberation, alteration and checking of feasibility played a crucial role in achieving the instruments' equivalence and minimizing biases. These phases were the result of effort and collaboration by 3 teams. The working group shared their candid views by identifying errors in provisional translations and suggesting appropriate modifications, with reasons. FGDs (38), conducted by the field research team using cognitive interviews (39) with informants helped not only in determining informants' understanding and cultural relevance of items but also in getting their inputs to create appropriate instructions and culturally relevant items. Finally, the team of multidisciplinary translators, which was considered better than independent translators (32), discussed all items and instructions and reached a consensus, while acknowledging the inputs from the working group and FGDs and ensuring congruent cross-cultural translation (18,40).

An important addition to this adaptation was the involvement of the developer of the instruments (35). It was an important practice to apply the technical, conceptual and even content understanding of the original developer of the instrument in the translated version. Finally, further authentication of the quality of adaptation was achieved via the formal approval of the developer himself.

FGDs and the final testing that were conducted in a school setting ensured that the adapted instruments had relevance for local informants. It is pertinent to mention that schools in Pakistan are generally not involved in research or child assessments. However, our collaboration with the teachers' professional capacity-building organization (the Teachers' Resource Centre) was extremely useful and played a vital role in convincing the schools' administration and encouraging parents, children and teachers to participate actively in the research.

It is important to highlight that the child behaviour problems instruments have been translated in both developed and developing countries but, interestingly, among developing countries only a few have translated all 3 parallel school age instruments available, i.e. the YSR 11-18, CBCL 6-18 and TRF 6-18, to achieve multi-informant views of a child's behaviour (23). Moreover, very limited validation studies from developing countries are available that have reported the qualitative adaptation ofall 3 parallel school-age instruments (41). Our study not only illustrates the rigorous and iterative process of adaptation of all 3 parallel instruments conducted in collaboration with the instruments' developer but also take a step forward in proposing a systematic model to conduct qualitative adaptation in a developing-country setting.

It is important to mention here that investigators were involved in every phase of adaptation to monitor quality and ensure smooth transition of this process.

A limitation ofthe study was that the instruments were tested on informants only in Karachi, a cosmopolitan city that has people from all ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds. The relevance of the adapted version is for the communities which have similar linguistic and cultural characteristics.

Our primary focus was to conduct and highlight the steps of the qualitative adaptation of child behaviour problems instruments from a developing country context. Certainly, quantitative adaptation is required that will further ensure the validity of the instrument. However, we believe that it is necessary to determine cultural relevance and to conduct a thorough qualitative adaptation of the instruments before moving on to determining their psychometrics (17).

Conclusions

To ensure the instruments' quality and equivalence for cross-cultural research in developing countries, we propose a rigorous and systematic model to achieve effective cultural adaptation of psychometric instruments. This process followed 6 meticulous phases in order to achieve conceptual, content, semantic and technical equivalences with the original English version. We conceived and refined this model by conducting qualitative adaptation of 3 parallel, multi-informant child behaviour problems instruments in Pakistan.

Acknowledgement

We are very grateful to the working group of experts, the translation team, field team, Teachers' Resource Centre and schools, especially the children, teachers and parents, for participating in the adaptation process. We are also thankful to Dr Thomas Achenbach for his keen involvement and technical advice during this process of adaptation. We appreciate the support of Ramani Sunderaju from ASEBA.We are also grateful to Dr Rakshanda Hussain for giving her valuable feedback on the manuscript.

Funding: Not applicable. Competing interests: None declared.

References

- O'Connell ME, Boat T, Warner KE, editors. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people: progress and possibilities. Washington: National Academies Press; 2009.

- Prevention of mental disorders: effective interventions and policy options. Summary report. A report of the World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse in collaboration with the Prevention Research Centre of the Universities of Nijmegen and Maastricht. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004 (http://www.who.int/ mental_health/evidence/en/prevention_of_mental_disor-ders_sr.pdf, accessed 5 May 2014).

- Eapen V, Jairam R. Integration of child mental health services to primary care: challenges and opportunities. Ment Health Fam Med. 2009 Mar;6(1):43-8.

- Knapp M, King D, Healey A, Thomas C. Economic outcomes in adulthood and their associations with antisocial conduct, attention deficit and anxiety problems in childhood. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2011 Sep;14(3):137-47. PMID:22116171

- Tremblay RE. Developmental origins of disruptive behaviour problems: the 'original sin' hypothesis, epigenetics and their consequences for prevention. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2010 Apr;51(4):341-67. PMID:20146751

- Bongers IL, Koot HM, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Predicting young adult social functioning from developmental trajectories of externalizing behaviour. Psychol Med. 2008 Jul;38(7):989-99. PMID:18047767

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Show me the child at seven: the consequences of conduct problems in childhood for psychosocial functioning in adulthood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005 Aug;46(8):837-49. PMID:16033632

- Koot HM, Verhulst FC. Prevalence of problem behavior in Dutch children aged 2-3. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1991;367:1-37. PMID:1897379

- Shenoy J, Kapur M, Kaliaperumal VG. Psychological disturbance among 5- to 8-year-old school children: a study from India. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998 Feb;33(2):66-73. PMID:9503989

- Javo C, R0nning JA, Handegârd BH, Rudmin FW. Social competence and emotional/behavioral problems in a birth cohort of Sami and Norwegian preadolescents in Arctic Norway as reported by mothers and teachers. Nord J Psychiatry. 2009;63(2):178-87. PMID:19214866

- Woo BS, Ng TP, Fung DS, Chan YH, Lee YP, Koh JB, et al. Emotional and behavioural problems in Singaporean children based on parent, teacher and child reports. Singapore Med J. 2007 Dec;48(12):1100-6. PMID:18043836

- Roberts RE, Attkisson CC, Rosenblatt A. Prevalence of psycho-pathology among children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 1998 Jun;155(6):715-25. PMID:9619142

- 13. Avan B, Richter LM, Ramchandani PG, Norris SA, Stein A. Maternal postnatal depression and children's growth and behaviour during the early years of life: exploring the interaction between physical and mental health. Arch Dis Child. 2010 Sep;95(9):690-5. PMID:20660522

- Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, Conti G, Er-tem I, Omigbodun O, et al. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet. 2011 Oct 22;378(9801):1515-25. PMID:22008427

- Bhui K, Mohamud S, Warfa N, Craig TJ, Stansfeld SA. Cultural adaptation of mental health measures: improving the quality of clinical practice and research. Br J Psychiatry. 2003 Sep;183:184-6. PMID:12948986

- Vijver FJRvd. Poortinga YH. Conceptual and methodological Issues in adapting tests. In: Hambleton RK, Merenda PF, Spiel-berger CD, editors. Adapting educational and psychological tests for cross cultural assessment. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005.

- Malda M. Vijver FJRvd, Srinivasan K, Transler C, Sukumar P, Rao K. Adapting a cognitive test for a different culture: An illustration of qualitative procedures. Psychology Science Quarterly. 2008;50(4):451-68.

- Flaherty JA, Gaviria FM, Pathak D, Mitchell T, Wintrob R, Richman JA, et al. Developing instruments for cross-cultural psychiatric research. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1988 May;176(5):257-63. PMID:3367140

- 19. Bruckner TA, Scheffler RM, Shen G, Yoon J, Chisholm D, Morris J, et al. The mental health workforce gap in low- and middle-income countries: a needs-based approach. Bull World Health Organ. 2011 Mar 1;89(3):184-94. PMID:21379414

- Saraceno B, van Ommeren M, Batniji R, Cohen A, Gureje O, Mahoney J, et al. Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2007 Sep 29;370(9593):1164-74. PMID:17804061

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington (VT): University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2001.

- Dulcan MK, editor. Dulcan's textbook of child and adolescent psychiatry. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Publishing; 2010.

- The ASEBA approach [Internet]. Burlington (VT): Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (http://www.aseba. org/, accessed 5 May 2014).

- ASEBA research updates from around the world [Internet]. Burlington (VT): Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (http://www.aseba.org/research/research.html, accessed 5 May 2014).

- Merrell KW. Behavioral, social and emotional assessment of children and adolescents. 3rd ed. New York: Lawrence Erl-baum Associates; 2008.

- Gelfand DM, Drew CJ. Understanding child behavior disorders. 4th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing; 2003.

- Reynolds WM. Reynolds child depression scale. Odessa (FL): Psychological Assessment Resources; 1989.

- Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. Behavior assessment system for children. 2nd ed. Circle Pines (MN): AGS Publishing; 2004.

- Bracken BA, Keith LK. Clinical assessment of behavior. Lutz (FL): Psychological Assessment Resources; 2004.

- Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Childhood symptom inventory-4: screening and norms manual. Stony Brook (NY): Checkmate Plus; 2002.

- Merenda PF. Cross-cultural adaptation and educational and psychological testing. In: Hambleton RK, Merenda PF, Spiel-berger CD, editors. Adapting educational and psychological tests for cross-cultural assessment. Mahwah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2005.

- Harkness J, Pennell B-E. Schoua-Glusberg Au. Survey questionnaire translation and assessment. In: Presser S, Rothgeb JM, Couper MP, Lessler JT, Martin E, Martin J, et al., editors. Methods for testing and evaluating survey questionnaires. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons; 2004.

- Matias-Carrelo LE, Chavez LM, Negrôn G, Canino G, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Hoppe S. The Spanish translation and cultural adaptation offive mental health outcome measures. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2003 Sep;27(3):291-313. PMID:14510096

- Smit J, van den Berg CE, Bekker LG, Seedat S, Stein DJ. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of a mental health battery in an African setting. Afr Health Sci. 2006 Dec;6(4):215-22. PMID:17604510

- Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000 Dec 15;25(24):3186-91. PMID:11124735

- Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, McGorry P. Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. Lancet. 2007 Apr 14;369(9569):1302-13. PMID:17434406

- Okasha A, Karam E, Okasha T. Mental health services in the Arab world. World Psychiatry. 2012 Feb;11(1):52-4. PMID:22295010

- Knudsen HC, Vazquez-Barquero JL, Welcher B, Gaite L, Becker T, Chisholm D, et al. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of outcome measurements for schizophrenia. EPSILON Study 2. European Psychiatric Services: inputs linked to outcome domains and needs. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2000; (39):s8-14. PMID:10945072

- Process of translation and adaptation of instruments. Management of substance abuse. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012 (http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/ research_tools/translation/en/, accessed 5 May 2014).

- Sartorius N, Kuyken W. Translation of health status instruments. In: Orley KW, editor. Quality of life assessment in health care settings. Berlin: Springer; 1994.

- Bordin IA, Rocha MM, Paula CS, Teixeira MC, Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA, et al. Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), Youth Self-Report (YSR) and Teacher's Report Form (TRF): an overview of the development of the original and Brazilian versions. Cad Saude Publica. 2013 Jan;29(1):13-28. PMID:23370021

Association of cerebral palsy with consanguineous parents and other risk factors in a Palestinian population

S. Daher1,2 and L. El-Khairy1,3

ترابط الشلل الدماغي مع زواج الأقارب وعوامل الاختطار الأخرى لدى الفلسطينيين

سوزي ظاهر، لينا الخيري

الخلاصة: ستهدف هذه الدراسة إلى استقصاء الترابط بين عوامل الاختطار المعروفة والمستجدة للشلل الدماغي بين الفلسطينيين. وهي دراسة للحالات والشواهد أجريت وشملت 107 أطقال تتراوح أعمارهم بين 1 و15 عاما في مركز لإحالة حالات الشلل الدماغي في القدس، إلى جانب 233 طفلا بدون الشلل الدماغى كشواهد من مراجعي العيادات الخارجية في الضفة الغربية. وقد جمعت البيانات من السجلات الطبية ومن استبيان صمم خصيصا للدراسة يملؤه الوالدان. وبإجراء التحوف اللوجستي المتدرج اتضح أن زواج الأقارب والعيوب الولادية لدى الأفراد الآخرين من الأسرة تترابط ترابطاً إيجابياً مع الشلل الدماغي (نسبة الأرجحية = 4.62 بفاصلة ثقة 95% وتتراوح بين 2.07-10.3 بالنسبة لزواج الأقارب، ونسبة الأرجحية = 12.7 بفاصلة ثقة 95% وتتراوح بين 3.13 و51.7 بالنسبة للعيوب الولادية لدى أفراد آخرين من الأسرة) مما يدل عل وجود رتبط جيني وراثي محتمل). ومن عوامل الاختطار الأخرى: نقص الاكسجة في الفترة المحيطة بالولادة (نسبة الأرجحية = 92.5 بفاصلة ثقة 95% تتراوح بين 24.5-350)، نقص الوزن عند الولادة (نسبة الأرجحية = 4.98 بفاصلة ثقة 95% وتتراوح بين 2.01-12.3)، والتوائم المتعددة (نسبة الأرجحية = 9.25 بفاصلة ثقة 95% وتتراوح بين 1.29 و66.8)، وعدم وجود رعاية طبية في الفترة السابقة للولادة (نسبة الأرجحية = 5.22 بفاصلة ثقة 95% وتتراوح بين 1.18 و23.1)، ويقدم هذا النموذج التدرجي الأول من نوعه لعوامل الاختطار التي يعتد بها والتي يمكن تعديلها لدى الفلسطينين بينات مفيدة لأصحاب القرار السياسي.

ABSTRACT This case-control study investigated risk factors for cerebral palsy in a Palestinian population. Cases were 107 children aged 1-15 years at a cerebral palsy referral centre in Jerusalem; controls were 233 children without cerebral palsy from West Bank outpatient clinics. Data were collected from medical records and a structured questionnaire to parents. In stepwise logistical regression, consanguinity and birth deficits in other family members were positively associated with cerebral palsy (OR = 4.62; 95% CI: 2.07-10.3 and OR = 12.7; 95% CI: 3.13-51.7 respectively), suggesting a possible genetic link. Other risk factors were: perinatal hypoxia (OR = 92.5; 95% CI: 24.5-350), low birth weight (OR = 4.98; 95% CI: 2.01-12.3), twin births (OR = 9.25; 95% CI: 1.29-66.8) and no prenatal medical care (OR = 5.22; 95% CI: 1.18-23.1). This first stepwise model of significant and modifiable risk factors in our population provides useful evidence for policy-makers.

Association de l'infirmité motrice cérébrale chez l'enfant, de la consanguinité chez les parents et d'autres facteurs de risque dans une population palestinienne

RÉSUMÉ La présente étude cas-témoins a étudié les facteurs de risque d'infirmité motrice cérébrale dans une population palestinienne. Le groupe de cas était composé de 107 enfants âgés de 1 à 15 ans consultant dans un centre d'orientation-recours pour l'infirmité motrice cérébrale à Jérusalem et celui des témoins de 233 enfants non affectés par cette pathologie et ayant eu recours à des services de consultations externes en Cisjordanie. Les données ont été recueillies à partir des dossiers médicaux et d'un questionnaire structuré administré aux parents. À l'analyse de régression logistique par étapes, la consanguinité et les anomalies congénitales chez d'autres membres de la famille étaient positivement associées à l'infirmité motrice cérébrale (OR = 4,62 ; IC à 95 % : 2,07-10,3 et OR = 12,7 ; IC à 95 % : 3,13-51,7 respectivement), suggérant qu'un lien génétique était possible. D'autres facteurs de risque significatifs étaient les suivants : hypoxie périnatale (OR = 92,5 ; IC à 95 % : 24,5-350), faible poids de naissance (OR = 4,98 ; IC à 95 % : 2,01-12,3), naissances gémellaires (OR = 9,25 ; IC à 95 % : 1,29-66,8) et absence de soins médicaux prénatals (OR = 5,22 ; IC à 95 % : 1,18-23,1). Ce premier modèle par étape pour les facteurs de risque importants et modifiables dans notre population fournit des informations utiles pour les responsables de l'élaboration des politiques.

1School of Public Health, Al-Quds University, Abu Dies Campus, Jerusalem (Correspondence to S. Daher:

Received: 29/09/13; accepted: 03/02/14

EMHJ, 2014, 20(7): 459-468

Introduction

Cerebral palsy is the most common motor disability of childhood (l). It is caused by damage to the developing brain resulting in neurological and motor deficits. In adulthood mortality and morbidity from ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, cancer and trauma are higher in people with cerebral palsy than in the general population (2). The underlying causes of the condition remain under debate and vary from medical mismanagement at birth to multifactor steps which form a series of causal pathways (3). Limited research also suggests that there are population-specific factors which may produce unique risks (4). Better evidence about the contribution made by both known and emerging risk factors are important for prevention of the disorder.

Having consanguineous parents is a known risk factor for congenital disability and genetic disorders (5). Although the worldwide prevalence of cerebral palsy has remained stable at 2-2.5 per 1000 live births (4), there are no population-based birth prevalence studies among highly consanguineous populations. It is estimated that one-fifth of the world's population located in the Middle East, West Asia and North Africa and in emigrant populations now living in North America, Europe and Australia are consanguineous. A study conducted in Palestine in 2004 found that the rate of consanguinity was 45% of all marriages (6). Other estimated prevalence rates in the region are 68% in Egypt, 33% in Syrian Arab Republic, 58.1% in Jordan, 54.4% in Kuwait, 57.7% in Saudi Arabia and 50.5% in the United Arab Emirates (7). Despite this, studies into consanguinity and health in the region are limited. A study of Turkish children with cerebral palsy found consanguinity to be a top risk factor (8). This association of consanguinity with complex disorders such as cerebral palsy is new and the results are ambiguous (9). Some authors suggest consanguinity increases susceptibility to multifactorial diseases in addition to increased risks for autosomal recessive diseases compared with the general population (7). A more recent Jordanian study which examined global developmental disorders including cerebral palsy found that consanguinity was a major risk factor (9). Other evidence for developmental problems linked to consanguinity have been provided from the Syrian Arab Republic (10). A study in Palestine found higher reading disabilities in children with consanguineous parents (6,11). However, other risk factors of importance for cerebral palsy in the region have been suggested, such as hypoxia, low birth weight, jaundice and preterm birth (8,12).

Both cerebral palsy and consanguinity are public health issues in Palestine. This research—the first known study in Palestine—adds to the existing information and highlights an important health problem. This study aimed to examine the association of cerebral palsy with known and emerging risk factors, including consanguinity, in Palestinian children in order to present a model of the salient risk factors for Palestine.

Methods

Study design and setting

A case-control study design was used. The cases were selected from The Princess Basma Centre for the Disabled, Mount of Olives, Jerusalem, which is the national cerebral palsy rehabilitation centre for Arab children. Children under the age of 15 years are admitted free of charge for a period of 1 week to 3 months, depending on need. It is the only centre in Palestine which offers residential physiotherapy, special education, speech therapy, nursing services, social work and play. The unique holistic approach means that cases are referred by the Palestinian Ministry of Health (MOH), United Nations Relief and Work Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) and private clinics. Therefore, cases came from all over Palestine. The controls were selected from West Bank outpatient clinics and were matched to cases based on the same geographical location of residence.

The study was carried out from 19 January to 29 August 2011. A consent form was signed by all participants and permission for the study was obtained from Al-Quds University institutional review board and all the health-care providers.

Sample

The sample size was determined using the following case-control sample size equation:

N = (p0q0 + p1q1)(Z1-a/2 + Z1-ß)2/(P1-P0)2

where: p = proportion of exposure among cases; p0 = proportion of exposure among controls; q = 1-p1; q0 = 1-p0; a = 0.05; ß = 0.2-power of 80%, based on the relative risk of the exposure and size of sample from existing published studies. This was combined with the desired power of the statistical test (13): p0 = 0.049, p1 = 0.049 x 3.4 (RR) = 0.1666. From this, N = 105 for both cases and controls.

Males and females aged between 1-15 years were included in this study. The diagnostic criteria for cases were a physician's diagnosis of cerebral palsy and physician-documented risk factors in the patients' records. From those resident at the Princess Basma Centre during the research period, a convenience sample of 107 cases with their mothers were recruited. The controls were selected by systematic probability sampling from every other child attending outpatient clinics on the day of the research visit, with any diagnosis except cerebral palsy. Clinics were chosen randomly from MOH and UNWRA registries; private clinics are not registered so local physicians were asked to identify suitable clinics in the different geographical locations. A total of 223 controls were included as cerebral palsy is a rare condition so a 1:2 ratio of cases to controls was used; 92 (41%) controls were recruited from MOH clinics, 22 (10%) from private and 109 (49%) from UNRWA clinics in the West Bank. The location of the clinics were classified into north, middle and south region in line with the administrative divisions of the Palestinian Authority and controls were matched to cases in terms of geographical location of residence. Any cases or controls whose medical documentation was absent were excluded. There were 13 case exclusions due to omissions in their files. None of the cases refused to participate and 3 of the controls declined.

Data collection

Data were collected in the same way for cases and controls using a structured questionnaire (Daher S, unpublished questionnaire, 2011) that was filled by the investigator from data in the medical records and an interview with mothers in Arabic. This included demographic data of the parents, characteristics of the pregnancy and delivery, and information about the child including the child's diagnosis (the distribution, tone and severity of cerebral palsy).

Variables

Through a PubMed literature search in January 2011, known risk factors for cerebral palsy were identified and a list of variables was drawn up as the basis for the questionnaire. Data on the following variables were obtained from the children's medical records: place of delivery [Palestinian Authority Ministry of Health hospital (MOH), private or nongovernment hospital (NGO), Palestinian Red Crescent hospital]; type of delivery [trauma, normal spontaneous vaginal delivery, instrument assisted (forceps, vacuum), breech birth, caesarean section; reason for caesarean]; prematurity (no/yes; exact gestational age); multiple pregnancies (no/yes); vanishing twin (no/ yes); perinatal hypoxia (no/yes); low birth weight (< 2500 g/< 1500 g; exact weight); incubation (no/yes; length of time); postnatal problems (haemorrhage/bleeding; other to be specified); perinatal jaundice (no/yes; bilirubin levels; documented length of time with jaundice); and congenital abnormalities (no/yes). Data on other relevant variables were obtained from interviews with mothers: parents' age (mother and father); parents' education (classified according to local examinations: below tawghi, tawghi, college diploma, university); parents' socioeconomic status [occupation of father and mother: initially classified using the International Standard Classification of Occupations 2008 (14) and grouped into professional, skilled, semiskilled, unemployed]; consanguineous parents (no/yes; 1st cousins, 2nd cousins, more distant family relations); any close or extended family members with physical or cognitive deficits from birth (no/ yes; disability to be specified); fertility treatment (type to be specified); and thrombophilia/clotting disorder (no/ yes). All variables except sociodemo-graphic variables were defined using Taber's cyclopedic medical dictionary (15).

Validation

Discussions as to the content and format of the questionnaire took place with multidisciplinary professionals who work at the hospital. A pilot study was used to verify that the questions were clear, the duration of the questionnaire was reasonable and that the questions, although of a personal nature, were not embarrassing. The questions appeared to have face validity; this was judged to be the case after the pilot study. As a result of the pilot study a question regarding the families' income was removed, as there was no objective way of verifying this. Socioeconomic status was therefore evaluated based on education and father's profession. The questionnaire was reviewed by 1 specialist paediatricians in the field of cerebral palsy and 2 general practitioners to judge the content validity. The use of medical records was important for criterion validity. The structure and content of medical records were similar for cases and controls, incorporating standardized patient record forms and documentation. Medical records were cross-checked with the information given. Consanguinity data was reliant on the mothers' reporting, but as such a marriage is considered normal no stigma would deter honest responses. All interviews we conducted by the first author and the use of medical records may have been beneficial in minimizing recall bias and any interviewer bias.

Statistical analysis

The data were first analysed by descriptive statistics including means and standard deviation (SD) and percentages. The t-test was used to investigate the difference in means. Univariate analysis for single directional crude associations and the chi-squared test for cross-tabulation were used to investigate whether proportions across more than one category among 2 or more independent groups were the same. Fisher exact test was used for small numbers. Logistic regression was used to test relationships between 2 non-continuous variables and for model building. Each variable was entered into a stepwise logistical regression and adjusted for all other variables in the study to ascertain if the variable was confounded. All analysis was conducted 2-tailed with P < 0.05 significant. As the study set out to find the most significant risk factors for Palestine and to build the first known model for Palestinians, interaction was not tested. The small numbers in the study and the lack ofpossibility for generalization also informed the decision not to focus on possible interactions. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS, version 19 statistical software.

Results

The demographic data for the 107 cases and 223 controls are presented in Table 1. There was no statistically significant difference between the mean age of the case and control groups [3.87 (SD 2.71) years and 4.17 (SD 3.94) years respectively] (P = 0.47). There were slightly more males than females in both groups (malefemale ratio 1.18 for cases and 1.12 for controls). The great majority of mothers of both groups were housewives, and when mothers did work most were in professional employment. There was no statistically significant difference in the age ofmoth-ers or fathers comparing the case and the control groups.

Table 1 shows that significantly more of the cases than controls were born to parents who were 1st cousins (34.6% versus 17.9%) or 2nd cousins (8.4% versus 1.3%) (P < 0.001). A family history of birth deficits was reported for 15 (14.0%) cases and 4 (1.8%) controls.

Table 2 shows the birth characteristics of the cases and controls. There was a statistically significant difference between the mean weight of cases and controls at delivery, with the cases having lower birth weight [2686 (SD 902) g versus 3183 (SD 600) g] (P < 0.001). Mean gestational age was significantly lower in cases than controls [36.4 (SD 5.2) weeks versus 38.5 (SD 2.2) weeks] (P < 0.001). Over half of the cases (58.9%) were incubated after delivery compared with only 6.3% of controls and the mean time spent under incubation was significantly longer for cases. Jaundice was noted for 18.7% of cases versus 7.6% ofcontrols and the duration of jaundice was significantly longer for cases.

A high proportion of the cases were delivered by caesarean section (48,44.9%) compared with only 58 (26.0%) of the controls. The reasons for caesarean section differed between cases and controls. For infants with cerebral palsy most of the caesarean deliveries were due to long labour, premature rupture of membranes, multiple births and fetal distress. For the controls the reasons included having all previous deliveries by caesarean section, loss of amniotic fluid, no contractions and the health of the mother. More of the control mothers (17.8%) were aware ofthe reason for their caesarean section than were case mothers (7.3%).

Table 3 shows the regression analysis for parents' consanguinity (1st or 2nd cousins) and other relations (more distantly related members of the same family). Cousin consanguinity was a significant risk factor for cerebral palsy (OR = 3.23; 95% CI: 1.93-5.39) (P < 0.001), whereas more distant family relations was not a significant risk.

Table 4 summarizes the univariate analysis for all the study variables.

Pregnancy and delivery variables that were significantly associated with a higher risk of cerebral palsy were: birth weight < 2500 g (OR = 4.60); caesarean section delivery (OR = 2.65); gestational age < 37 weeks (OR = 2.90); multiple births (OR = 11.4); infection during pregnancy (OR = 4.80); infection during delivery (OR = 5.00); congenital abnormalities (OR = 2.41); and hypoxia at birth (OR = 65.8). Other factors that were significantly associated with cerebral palsy were: no medical care during pregnancy (OR = 5.50); and delivery in MOH hospital (OR = 2.70).

Having consanguineous parents increased the risk of cerebral palsy almost 3-fold (OR = 2.85) and having other children with disabilities in the family increased it almost 9-fold (OR = 8.90) (Table 4). The numbers of cases and controls with a family history of birth deficits were small, but of the 15 case children with disabilities in other family members 6 also had cerebral palsy in the family, all from consanguineous parents. For the controls only 4 children had cases of disability in the family: 2 were cerebral palsy, 1 was postnatally acquired and 1 was due to hypoxia during delivery.

The main risk factors for cerebral palsy were found by using a stepwise regression model (Table 5). All risk factors were entered individually in order of significance and removed if significance was lost. The coefficient in the analysis remained constant showing that there were no extraneous variables confounding the result. Of the 6 factors which remained out ofall the study variables entered into the model, perinatal hypoxia was associated with the highest risk (adjusted OR = 92.5; 95% CI: 24.5-350). Two family variables were significant risks for cerebral palsy: consanguineous parents (aOR = 4.62; 95% CI: 2.07-10.3); and presence of birth deficits in other family members (aOR = 12.7; 95% CI: 3.13-51.7). Other risk factors that remained significant in the final model were: low birth weight (aOR = 4.98; 95% CI: 2.01-12.3); multiple births (twins) (aOR = 9.25; 95% CI: 1.29-66.8); and no prenatal medical care (aOR = 5.22; 95% CI: 1.18-23.1).

Discussion

This study has produced the first model of risk factors for cerebral palsy among Arab children from the West Bank and Jerusalem. The main findings of this study are that crude associations were significant for many known and emerging population-specific risk factors for cerebral palsy. When adjusted for all variables with elimination of confounding variables we found that perinatal hypoxia, low birth weight, multiple births (twins), no prenatal medical care, other birth deficits in the family and consanguinity remained as significant risk factors.

Among the known risk factors for cerebral palsy, one of the first to be discussed in the literature was caesarean section, which is considered protective or associated with a slight rise in risk (16). In the present study 45.3% of the cases had been born by caesar-ean section compared with 26.3% of controls, and this was significant in the univariate analysis (OR = 2.65; 95% CI: 1.61-4.34). However, the variable was not retained in the final regression model. All parents were asked the reason for the caesarean section, and of particular interest is the high number of mothers, particularly among cases, who were unaware ofthe reason. Indeed 10% more of the cases did not know why their child had been delivered by caesarean. In Palestine this is a decision taken by the doctor; there are no elective caesarean sections at 39 weeks of gestation as is common in other countries (17). It should be remembered that with any observational study the data were collected post hoc and therefore we cannot know if the association was due to poor medical management and not a common, unknown confounding factor. How many cases were due to suboptimal obstetric response (not expediting delivery) is not known. Clinical signs sufficient to warrant a caesarean section may only be recognizable after the damage has occurred. Offering mothers caesarean section at 39 weeks is not currently available as a birthing plan in Palestine.

The strongest association with cerebral palsy in our study was with perinatal hypoxia. Hypoxia was documented for 45.8% cases and 1.8% of controls and this was the most important risk factor that remained in the final multiple regression model (OR = 92.5; 95% CI: 24.5-350). Lack of oxygen is believed to be an important and preventable cause of cerebral palsy and for many years no research was done to look at other risk factors for cerebral palsy (18). Indeed this belief underpinned much of the justification for the practice of fetal monitoring in labour and the increase in caesarean section rates.

No medical care in pregnancy was another new, previously unresearched risk factor. With no national health system in Palestine, whether, when and how a woman seeks medical care in pregnancy is solely in the control of the individual. As primary health care in Palestine is available and is not expensive the reasons why 11.2% and 2.2% of case and control mothers respectively did not having regular prenatal checkups are not known and requires further investigation. Lack of regular prenatal check-ups was a significant risk factor for cerebral palsy in the multiple regression analysis (OR = 5.22; 95% CI: 1.18-23.1). From this association we can assume that the benefits of routine ultrasound in early pregnancy and other checks are important for prevention. We could not identify any studies to compare with this result.

The mean birth weight of cases and controls were 2686 kg and 3183 kg respectively, and low birth weight (< 2500 g) was another significant variable in the final regression model (OR = 4.98; 95% CI: 2.01-12.3). Different explanations can be suggested for this association of low birth weight with cerebral palsy: first, that low birth weight and cerebral palsy is an epiphenomenon; secondly, that intrauterine growth restriction causes the conditions responsible for brain damage; thirdly, that growth restriction or low birth weight makes the child more vulnerable to hypoxia; and finally that the damage has already occurred and that low birth weight is related to earlier pregnancy factors such as malformations or viral infections. The underlying mechanisms are unclear (18).

Another significant variable in the risk ofcerebral palsy was multiple births, found in 10 (9.3%) case and 2 (0.9%) control mothers (all the multiple births were twins, no higher order births). Despite the small numbers twin births proved to be a significant risk at all levels of analysis and remained in the regression model (OR = 9.25; 95% CI: 1.29-66.8). Multiple births have greater risks of complications particularly for the second-born child. Further they have been shown to be associated with low birth weight, preterm delivery and death of the co-fetus (19).

Another of the variables we studied—family members with birth deficits—was defined to include any close or extended family members with physical or cognitive deficits from birth. Due to this wide definition the possibility of confounding factors cannot be overlooked. This association was found to be significant, with 14.0% of cases and 1.8% of controls having other family members with birth deficits, a variable which was highly significant in the multiple regression analysis (OR = 12.7; 95% CI: 3.13-51.7). As part of family history it may encompass a range of influences, direct and less direct, genetic factors or maybe intergenerational environmental effects. Further research is needed with perhaps a more specific definition. Other studies which focused on the risk of a second child having cerebral palsy where one child had already been diagnosed produced an OR of 1.6 ofrecurrence (20).

The etiology of cerebral palsy may vary between countries, and therefore population-specific factors of cultural relevance such as consanguinity are important to investigate. One of the main objectives ofour study was to see ifthere was an association between cerebral palsy and consanguinity. The results of the study showed that 47.7% of cases versus 24.2% of controls were from consanguineous parents (1st or 2nd cousins) and this was an important variable remaining in the regression model (OR = 4.62; 95% CI: 2.07-10.3). In other published research consanguinity was also found to be among the top risk factors (8). The results of our study provides some evidence of a genetic etiology for cerebral palsy. More research into possible genetic links with cerebral palsy will improve our understanding of the pathophysiology of the disorder. The significance of emerging risk factors can be explained by the belief that well-known risk factors do not present the full picture of etiology. Consanguinity is a social issue which needs to be addressed by government and nongovernment agencies, and there is a need for awareness through education. For many populations inter-marriage has a number of perceived benefits, for example, keeping money in the family and families being known to each other (21). Available research into a genetic link to cerebral palsy is mostly in the form of small-scale studies and case reports (22,23). Most estimates place the proportion of cerebral palsy cases with genetic etiology at between 1% and 2%, and it has been argued that cerebral palsy could be both genetic in origin as well as the result of environmental insult at any point during central nervous system development (24). With 60% of cerebral palsy cases having an unknown cause other than suspected prepartum risk factors (25) means this area warrants attention, especially in countries with a large consanguineous population. Small-scale studies have identified nonsense mutations (26) and for consanguineous populations there may be genes which have temporal or site-specific targets that act on the developing brain. At present access to genetic diagnostic testing is limited. There are at least 20 different syndromes associated with cerebral palsy (23) and it is possible there are more genetic syndromes which remain undiagnosed.

The results of this study have many similarities with an Egyptian study conducted in 2011, in which the most significant risk factors for cerebral palsy were found to be low birth weight, preterm birth, hypoxia and consanguineous marriage (12). In that study preterm birth lost significance in the stepwise model, as did other known risk factors such as parents' socioeconomic status.

The importance of this study is that it is the first known study in Palestine identifying risk factors for Palestinian children. There are no known case-control studies or other comparable studies in the region. Subsequent studies with more power would provide more information about the factors investigated here. Identifying modifiable factors leads to the possibility of prevention. The study has provided some evidence for the need for heightened awareness about the link between consanguinity and cerebral palsy. This requires a cultural change perhaps realized through health promotion incorporating advice from health providers and social marketing campaigns. Deep-seated cultural practices are obviously hard to change and require time.

Our results concerning perinatal hypoxia suggest that when a case of cerebral palsy is identified at birth there is a need for an in-hospital inquiry aimed at possible improvement of birth practices for future avoidance. Our study also highlighted the need for greater regular prenatal check-ups. This requires an educational change so that mothers are made aware of the importance ofvisits for their health and their baby's health.

Limitations

As this was a small-scale study we cannot state any claim to generaliz-ability of the results and a study with a larger sample is needed. Concerning bias the population was a homogenous group with controls representative of cases in terms of geographical area of residence. This was important to increase representativeness as convenience sampling in one treatment centre was used to recruit cases. How many Palestinian children do not access any services, and their location of residence, remains unknown, as there is no cerebral palsy register, but this is acknowledged as a limitation in terms of the representativeness of the study. Also all the limitations that accompany an observational case-control study need to be borne in mind. Incidence/ prevalence bias should be considered, because the use of incident cases rather than prevalent cases is deemed better in case-control studies, although this may not be applicable to cerebral palsy which by definition is non-progressive. In addition, this research incorporated a non-standardized questionnaire as a means of data collection, crossed-checked with medical records, which pose a weakness in terms of reliability and validity. Information bias is also a possibility with any case-control study; however, there was only the possibility of recall bias for demographic variables. There are no standardized questionnaires in existence that address the areas of our study, and there is no national cerebral palsy register in Palestine. Selection bias is always a concern in case-control studies so it needs to be noted that the researchers had no control over who would be treated at The Princess Basma Centre. The research continued until the sample size had been achieved. This study was unique; with no registers available data collection options are limited. Adjustment was made for gestation, sex and all study variables to avoid confounding. For the factors which this paper addresses the possibility of bias is considered minimal.

Conclusion

To conclude, among several other known risk factors such as perinatal hypoxia and multiple births, consanguinity of parents was significantly associated with cerebral palsy in Palestinian children.

Acknowledgement

This research does not represent the views ofany institution or funding body. Funding: This research received no outside funding.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- Suvanand S, Kapoor SK, Reddaiah VP, Singh U, Sunda-ram KR. Risk factors for cerebral palsy. Indian J Paediatr. 1997;64(5):677-85.

- Shankaran S. Prevention, diagnosis and treatment of cerebral palsy in near-term and term infants. Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;51(4):829-39. PMID:18981806

- Keogh JM, Badawi N. The origins of cerebral palsy. Curr Opin Neurol. 2006 Apr;19(2):129-34. PMID:16538085

- Stanley F, Blair E, Alberman E, editors. Cerebral palsies: epidemiology and causal pathways. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

- Hamamy H. Consanguineous marriages, preconception consultations in primary health care settings. J Community Genet. 2012 Jul;3(3):185-92. PMID:22109912

- Assaf S, Khawaja M. Consanguity trends and correlates in the Palestinian Territories. J Biosoc Sci. 2009 Jan;41(1):107-24. PMID:18549512

- Hamamy H, Antonarakis SE, Cavalli-Sforza LL, Temtamy S, Romeo G, Kate LP, et al. Consanguineous marriages, pearls and perils: Geneva International Consanguinity Workshop Report. Genet Med. 2011 Sep;13(9):841-7. PMID:21555946

- Erkin G, Delialioglu SU, Ozel S, Culha C, Sirzai H. Risk factors and clinical profiles in Turkish children with cerebral palsy: analysis of 625 cases. Int J Rehabil Res. 2008 Mar;31(1):89-91. PMID:18277211

- Masri A, Hamamy H, Khreisat A. Profile of developmental delay in children under five years of age in a highly consanguineous community: a hospital-based study—Jordan. Brain Dev. 2011 Nov;33(10):810-5.

- Othman H, Saadat M. Prevalence of consanguineous marriages in Syria. J Biosoc Sci. 2009 Sep;41(5):685-92. PMID:19433003

- Abu-Rabia S, Maroun L. The effect of consanguineous marriage on reading disability in the Arab community. Dyslexia. 2005 Feb;11(1):1-21. PMID:15747804