Sustaining tobacco control is crucial during this pandemic, to protect the gains made by the Eastern Mediterranean in reducing tobacco consumption [5]. This webpage lays out the current evidence on tobacco’s impact on the COVID-19 pandemic and identifies practical actions to integrate the WHO FCTC guidelines and MPOWER strategies into countries’ pandemic response.

Introduction and background

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a major disruptor in global public health. The emergence of SARS-COV 2, a deadly and novel respiratory pathogen, its unprecedented, and rapid spread globally, and its devastating impact on health systems and national economies have shifted the world’s attention to this one health emergency. Yet, this communicable disease is intricately entwined with noncommunicable diseases and tobacco as the major risk factor, as evidence mounts on the determinants of severity and fatality from COVID-19.

Putting tobacco control on hold while the world grapples with the COVID-19 pandemic is counterproductive. Already, research is accumulating that delineates the critical role of tobacco use in COVID-19 disease severity and risk of death. Smoking, and tobacco-caused noncommunicable diseases confer a higher risk for worse outcomes with COVID-19. The experience in the United Kingdom, where unprecedented numbers of smokers have quit during the pandemic, highlights the opportune “teachable moment” that the pandemic offers to push forward the tobacco control agenda as a strategy to mitigate the adverse health impact of COVID-19. Conversely, the recent actions of the tobacco industry in obscuring tobacco’s role in the pandemic, currying favour with governments through corporate social responsibility for pandemic relief efforts and promoting the sales of their products through enhanced online marketing highlight the need for sustained vigilance and implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) Article 5.3 guidelines. Clearly, countries must sustain implementation of the WHO FCTC and MPOWER strategies (i.e. key tobacco control interventions that are fully subordinate to the WHO FCTC) during the time of COVID-19.

In May 2013, the World Health Assembly of the World Health Organization adopted and approved a set of voluntary targets for the control of noncommunicable diseases. All countries have shown commitments to these targets, which include a 30% relative reduction in tobacco use by the year 2025. The Eastern Mediterranean countries joined the rest of the world when the UN General Assembly formally adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in September 2015. Target 3.4 under the overall health goal (SDG 3) is a one-third reduction of noncommunicable disease-related premature deaths by 2030. Target 3.A of the goal is to strengthen the implementation of the WHO FCTC in all countries, as a means of reaching SDG 3 by 2030. In 2018, during the 65th Session of the WHO Regional Committee for the Eastern Mediterranean, Member States adopted both the Regional Strategy and Action Plan for Tobacco Control and the Regional Framework for Tobacco Control to accelerate full ratification and implementation of the WHO FCTC and MPOWER measures, in a bid to support its Member States to attain the 2025 tobacco use reduction and 2030 SDG targets.

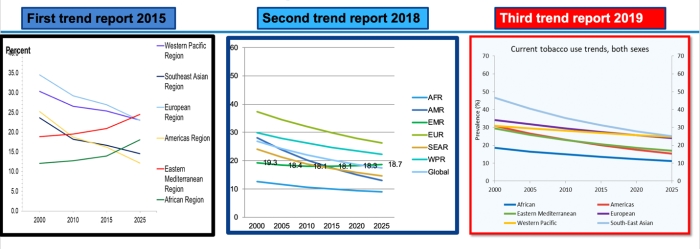

These political commitments are reflected in the improvement in projected trends of tobacco consumption for the Region. The Eastern Mediterranean has achieved significant gains in tobacco control in recent years. Previous analyses in 2015 [1] and 2018 [2] demonstrated the Region was lagging behind the rest of the world in reducing tobacco use, with the Eastern Mediterranean being the only Region expected to have an increase in tobacco use among males from 2010-2025. This dire prediction was reversed in the latest projection analyses; for the first time, projected tobacco consumption rates declined [3], reflecting the Region’s intensified efforts to implement the WHO FCTC (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Comparison of trendline projections, 2015, 2018 and 2019

Sources: WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco smoking 2000–2025, first, second and third editions. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015, 2018 and 2019.

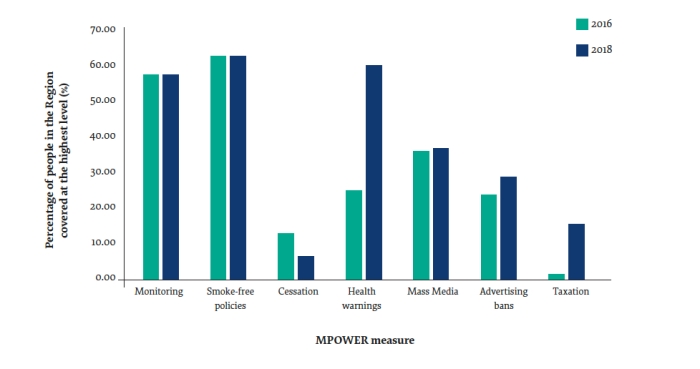

Progress in tobacco control within the Region is reflected in the increase in countries performing at the highest level for MPOWER strategies [4]. Yet current surveillance data reveal that the region still needs to strengthen efforts towards full ratification and implementation of the WHO FCTC and MPOWER measures (Figure 2). And the current pandemic has impeded, and in some cases, put a halt to country tobacco control efforts, threatening to undo the progress in recent years.

Figure 2: MPOWER coverage (at the highest level) in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 2016 and 2018

Source: ElAwa F, et al. 2020. The status of tobacco control in the Eastern Mediterranean Region:

progress in the implementation of the MPOWER measures. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 26(1): 102-107.

Tobacco and COVID-19: what’s the evidence?

The COVID-19 pandemic is unprecedented, and SARS-COV-2 is a completely new pathogen. Data and information continue to accrue, and the evidence is expected to evolve as we learn more about this virus over time. This section presents current evidence as of July 2020.

Smoking and COVID-19

Risk of infection

Whether smokers are at higher risk of COVID-19 infection has yet to be determined. However:

Smokers are more susceptible to both bacterial and viral infections, including the MERS-COV, which is remarkably similar to SARS-COV2.

Hand to mouth contact is acknowledged as one pathway to get infected with COVID-19. Hand to mouth contact occurs frequently and repeatedly when smoking.

Smokers are unable to keep their masks on while smoking. If they smoke in public places where other unmasked smokers congregate, it raises the likelihood of getting infected.

The COVID-19 virus enters human cells through a receptor in the respiratory tract called ACE-2. Smoking up-regulates the ACE-2 receptor, causing it to replicate and provide more entry points for the virus. This may make smokers more susceptible to getting the infection.

Severity of infection

Multiple studies document that smokers infected with COVID-19 risk having more severe disease and are more likely to require ventilation support [6,7,8].

Smokers are more likely to have co-morbid conditions caused by their tobacco use, including heart disease, hypertension, chronic lung disease, diabetes and cancer, which have been associated independently with more severe COVID-19 disease and increased risk of death [4,5].

Risk of death

In China, of 1099 patients with COVID-19, 12.4% who were current smokers died, required intensive care unit admission or mechanical ventilation, compared to 4.7% among those who never smoked [6].

In the largest review of studies to date of COVID-19 patients, smokers were more likely to die compared to never smokers [7].

Waterpipe use and COVID-19

Risk of infection

Waterpipe smoking is usually a social activity, with sharing of a single mouthpiece and hose by users who are physically close to each other [8]. It precludes the use of face masks, and there is frequent hand to mouth contact. These facilitate the spread of SARS-COV-2 from one person to another.

The waterpipe apparatus provides a favorable environment for the virus to thrive [14]. Most cafés tend not to clean the waterpipe equipment, including the water jar, after each smoking session because washing and cleaning waterpipe parts is labour intensive and time consuming [15,16]. These factors increase the potential for the transmission of infectious diseases between users. This is consistent with evidence demonstrating that waterpipe use is associated with an increased risk of transmission of other infectious agents, including respiratory viruses, hepatitis C virus, Epstein Barr virus, Herpes Simplex virus, tuberculosis, Helicobacter pylori, and Aspergillus.

Waterpipe smoke is injurious to the respiratory tract, and may predispose the smoker to viral infections, including SARS-COV-2 [17].

Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), other electronic smoking devices (ESDs), heated tobacco products (HTPs) and COVID-19

Risk of infection

At present, there is no evidence regarding e-cigarette or HTP use and the risk contracting COVID-19. However:

E-cigarette, ESD and HTP use preclude the use of face masks and involves frequent hand to mouth contact. If users are in a shared public place, with other unmasked smokers close by, the transmission of the virus is facilitated.

There is concern that asymptomatic, infected users of these devices may be spreading the virus when generating aerosols [18].

Severity of infection

In the United States, the proportion of young people with severe cases of COVID-19 appears higher than in some other countries. One hypothesis for this difference is the higher prevalence of e-cigarette use by youth [19].

Young adults who smoked or used e-cigarettes had double the medical vulnerability to COVID-19 as compared to non-smokers/non-users [20].

There are no studies yet correlating progression of COVID-19 and use of e-cigarettes or HTPs. However, animal and human studies with these products have demonstrated altered cellular function and decreased immunity to viral agents [21,22,23].

Cellular and immune alterations and lung damage caused by e-cigarettes, ESDs and HTPs can be considered risk factors for the more severe manifestations and progression of COVID-19 [24].

The tobacco industry during the COVID-19 pandemic

Unlike other health issues, tobacco control has to contend with opposition from the tobacco industry. Tobacco companies are taking advantage of the current pandemic to further promote their products and protect their market share and profit margins. Some strategies that are actively in use include:

Obscuring tobacco’s role as a risk factor for severe disease

The tobacco industry is aggressively disseminating research, often conducted by authors who have received funding and other support from the tobacco industry and its partner organizations, that claim, ironically, a protective role for nicotine in COVID-19 infections. These studies, some of which have been shown to have serious methodologic flaws, attempt to downplay tobacco use as a risk factor for serious and potentially fatal disease [25].

In Italy, South Africa and Brazil, the tobacco industry lobbied governments to consider tobacco and vape shops as part of “essential” business [26].

Using pandemic relief to promote their image as good corporate citizens

The tobacco industry has historically employed corporate social responsibility tactics to bolster their social image, garner public legitimacy and win the trust of the community as a means to advance their economic interests. Article 5.3 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) clearly points out the “inherent contradiction” of corporate social responsibility activities, and calls for governments to ban these activities outright.

In Greece, Philip Morris International donated ventilators to the Greek government [27]. Similar donations of ventilators, personal protective equipment, sanitizing hand gel, alcohol, and money have been documented in numerous countries. This is ironic, given how the use of their product is a major risk factor for COVID-19 patients requiring ventilation support. Notably, the tobacco industry’s donations, a form of corporate social responsibility activity, are disproportionately lower in value than the cost of the damage tobacco use brings to the economy [28].

Promoting the online sales of tobacco products, e-cigarettes and other electronic smoking devices (ESDs) and heated tobacco products (HTPs) through aggressive online marketing

The Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids reports: “Tobacco and e-cigarette companies are engaging in pandemic-themed marketing even as health experts warn that smoking and vaping can increase risk of serious complications from COVID-19. Tobacco product marketing campaigns using COVID-19 references have been observed online, on social media, and through mobile text messages.” Some specific examples that they cite [29].

In Guatemala, Romania, Spain, Italy and other countries, Philip Morris International and British American Tobacco – the world's two largest tobacco companies – are appropriating "Stay at Home" social media hashtags promoted by governments and health authorities to instead market heated cigarette products IQOS and Glo, and e-cigarette Vype.

In the United States, e-cigarette makers and vape shops have engaged in pandemic-themed promotions such as free giveaways of protective masks with purchases and offering COVID-19 themed discounts (get 19% off nicotine e-liquids by entering the code COVID-19).

Philip Morris International has waived ID validation on delivery of IQOS in at least one country and references the COVID-19 crisis in at least 18 countries to promote special offers, “contactless delivery,” and home delivery of the product. These activities could undermine minimum age purchase restrictions intended to prevent sales to youth. The company has also promoted at-home music series and launched exclusive music videos to promote tobacco products online.

E-cigarette makers have also used the pandemic to make unproven and illegal health claims. In the United States, Bidi Vapor claimed on Instagram that “A bidi stick a day keeps the pulmonologist away.”

Tobacco control policy actions during the time of COVID-19

Evidence continues to mount regarding the fundamental role of tobacco use in conferring heightened risk for severe disease and mortality from COVID-19. Tobacco control should therefore be integrated into the pandemic response, to mitigate the health burden from COVID-19. This requires a sustained effort to continually implement sound tobacco control policies contained in the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) and highlighted by MPOWER. COVID-19 related practical actions that countries can adopt include the following:

M – MONITOR tobacco use and prevention policies

Incorporate questions about tobacco use, including the use of e-cigarettes or other electronic smoking devices (ESDs) and heated tobacco products (HTPs) in screening questionnaires for all patients undergoing COVID-19 testing and diagnostic work-up. Track disease outcome and severity by tobacco use status.

P – PROTECT people from tobacco smoke

Ban smoking and the use of waterpipes, e-cigarettes and other ESDs and HTPs in all public places, including multi-unit housing and cars with passengers, to reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission. Already, 15 countries in the Eastern Mediterranean Region have banned waterpipe use in both indoor and outdoor public areas as part of their COVID-19 pandemic response [29].

Strongly advice tobacco users (cigarette smokers, waterpipe users, vapers and those using HTPs) to avoid tobacco use inside their homes to protect their families from secondhand smoke.

Ensure that smoking, waterpipe use or vaping are not considered valid exemptions from using face masks in public.

O – OFFER help to quit tobacco

Ramp up cessation messaging in all health care settings and on mass media. Emphasize that quitting tobacco use can help mitigate the adverse health impact of COVID-19.

Integrate tobacco cessation into the package of essential clinical services for all persons suspected or diagnosed with COVID-19.

Include quitline/cessation programme information in all community advocacy and outreach materials on pandemic preparedness and COVID-19 prevention.

Facilitate online and other non-face-to-face cessation services and enable remote access to nicotine replacement products.

W – WARN about the dangers of tobacco

Widely disseminate the warning to all tobacco users that they are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 and have a higher risk of greater morbidity and mortality from the disease.

Inform the public about the likelihood of high risk of infection when sharing waterpipes.

Counter the disinformation promoted by the tobacco industry.

E – ENFORCE bans on tobacco advertising promotion and sponsorship

Strictly enforce the ban on online advertising and promotion of tobacco products, e-cigarettes and other ESDs.

Expose the deceptive marketing of the tobacco industry and how it is taking advantage of the COVID-19 pandemic as a marketing angle.

R – RAISE taxes on tobacco

Ensure that all tobacco, products and e-cigarettes and other ESDs are NOT included as “essential” goods.

Consider raising taxes on these products and using the tax revenues to help fund cessation programmes and pandemic control efforts

WHO FCTC Article 5.3: Protecting tobacco control policies from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry

Reject the tobacco industry’s attempts to provide support and donations for COVID-19 relief efforts.

Inform all sectors and the public about the true nature and purpose of the tobacco industry’s corporate social responsibility activities.

Require the tobacco industry to disclose information on its corporate social responsibility activities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This COVID pandemic has uncovered the potential opportunity to make a stronger case for tobacco control to be embedded in disaster and pandemic preparedness, linking tobacco control to the communicable disease agenda. Now more than ever, countries need to strengthen and sustain their efforts to ensure full implementation of the WHO FCTC and MPOWER measures, using strategic communications to frame tobacco control as integral to the pandemic response.

Priority policy actions

The following key policy actions should be prioritized:

M – MONITOR tobacco use and prevention policies

Incorporate questions about tobacco use, including the use of waterpipe, e-cigarettes or other electronic smoking devices (ESDs) and heated tobacco products (HTPs) in screening questionnaires for all patients undergoing COVID-19 testing and diagnostic work-up. Track disease outcome and severity by tobacco use status.

P – PROTECT people from tobacco smoke

Ban smoking and the use of waterpipes, e-cigarettes and other ESDs and HTPs in all public places, joining the 15 Eastern Mediterranean countries that have already adopted this policy measure.

O – OFFER help to quit tobacco

Integrate tobacco cessation into the package of essential clinical services for all persons suspected or diagnosed with COVID-19.

W – WARN about the dangers of tobacco

Widely disseminate the warning to all tobacco users that they are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 and have a higher risk of greater morbidity and mortality from the disease.

E – ENFORCE bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship

Strictly enforce the ban on online advertising and promotion of tobacco products, e-cigarettes and other ESDs.

R – RAISE taxes on tobacco

Consider raising taxes further on tobacco products and on e-cigarettes and other ESDs, and use the tax revenues to help fund cessation programmes and pandemic control efforts.

Article 5.3 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: Protecting tobacco control policies from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry

• Require the tobacco industry to disclose information on its corporate social responsibility activities during the COVID-19 pandemic.

References

[1] WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco smoking 2000–2025, first edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

[2] WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco smoking 2000–2025, second edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

[3] WHO global report on trends in prevalence of tobacco smoking 2000–2025, third edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

[4] El-Awa F, et al. The status of tobacco control in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: progress in the implementation of the MPOWER measures. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2020;26(1): 102-107.

[5] Al-Lawati JA, Mackay J. Tobacco control in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: the urgent requirement for action. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2020;26(1):6–8.

[6] Liu W, Tao ZW, Lei W, et al. Analysis of factors associated with disease outcomes in hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus disease. Chinese Medical Journal. 2020;133(9). DOI:10.1097/CM9.0000000000000775.

[7] Vardavas CI, Nikitara K. COVID-19 and smoking: a systematic review of the evidence. Tobacco Induced Diseases. 2020;18(March). DOI:10.18332/tid/119324.

[8] Patanavanich R, Glantz SA. Smoking is associated with COVID-19 progression: a meta-analysis. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2020;22(9). DOI:10.1093/ntr/ntaa082.

[9] Gupta S, Hayek SS, Wang W, et al. Factors associated with death in critically ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in the US. Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine. 2020; E1–E12. DOI:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3596.

[10] Grasselli G, Greco M, Zanella A, et al. Risk factors associated with mortality among patients with COVID-19 in intensive care units in Lombardy, Italy. Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine. 2020; E1–E11. DOI:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3539.

[11] Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;382. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa2002032.

[12] Simons D, Shahab L, Brown J, Perski O. The association of smoking status with SARS-CoV-2 infection, hospitalisation and mortality from COVID-19: a living rapid evidence review (version 5). 2020. DOI:10.32388/UJR2AW.6.

[13] Maziak W, et al. The global epidemiology of waterpipe smoking. Tobacco Control. 2015;24(Suppl 1):3–12.

[14] Tobacco and waterpipe use increases the risk of COVID-19. Cairo: WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; 2020 (http://w ww.emro.who.int/fr/tfi/know-the-truth/tobacco-and-waterpipe-users-are-at-increased-risk-of-covid-19-infection.html, accessed 14 September 2020).

[15] Daniels K, Roman N. A descriptive study of the perceptions and behaviors of waterpipe use by university students in the Western Cape, South Africa. Tobacco Induced Diseases. 2013;11(1).

[16] Koul P, et al. Hookah smoking and lung cancer in the Kashmir valley of the Indian subcontinent. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2011;2(2):519–24.

[17] Shekhar S, Hannah-Shmouni F. Hookah smoking and COVID-19: call for action. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2020;192(17):E462. DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.75332.

[18] Javelle E. Electronic cigarette and vaping should be discouraged during the new coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Archives of Toxicology. 2020;94(6):2261–2262. DOI:10.1007/s00204-020-02744-z.

[19] Drope J, Cahn Z, Douglas C, Liber A. What do we know about tobacco use and COVID-19? The Tobacco Atlas: 2020 (https://tobaccoatlas.org/2020/04/21/what-do-we-know-about-tobacco-use-and-covid-19/, accessed 14 September 2020).

[20] Adams SH, Park MJ, Schaub JHP, Brindis CD, Irwin CE Jr. Medical vulnerability of young adults to severe COVID-19 illness—data from the National Health Interview Survey. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2020;67:362–368. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.025.

[21] Madison MC, Landers CT, Gu B-H, Chang C-Y, Tung H-Y, You R, et al. Electronic cigarettes disrupt lung lipid homeostasis and innate immunity independent of nicotine. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2019;129:4290–304.

[22] Reidel B, Radicioni G, Clapp PW, Ford AA, Abdelwahab S, Rebuli ME, et al. E-cigarette use causes a unique innate immune response in the lung, involving increased neutrophilic activation and altered mucin secretion. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2018;197:492–501.

[23] Sohal SS, Eapen MS, Naidu VGM, Sharma P. IQOS exposure impairs human airway cell homeostasis: direct comparison with traditional cigarette and e-cigarette. European Respiratory Journal Open Research. 2019;5:00159–2018.

[24] Silva ALO, Moreira JC, Martins SR. COVID-19 and smoking: a high-risk association. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 2020;36(5):e00072020.

[25] Attempts to confuse the science linking smoking to COVID-19. London: University of Bath; 2020 (https://tobaccotactics.org/wiki/covid-19/, accessed 14 September 2020).

[26] Challenging classification of “essential businesses”. London: University of Bath; 2020 (https://tobaccotactics.org/wiki/covid-19/, accessed 14 September 2020).

[27] Chapman M. Big tobacco criticised for 'coronavirus publicity stunt' after donating ventilators. London: The Bureau of Investigative Journalism; 2020 (https://www.thebureauinvestigates.com/stories/2020-03-30/pmi-criticised-for-coronavirus-pr-stunt-ventilator-donation, accessed 14 September 2020).

[28] Tobacco Industry’s COVID donations vs. economic cost of tobacco. Thailand: Global Center for Good Governance in Tobacco Control; 2020 (https://ggtc.world/2020/04/23/tobacco-industrys-covid-donations-vs-economic-cost-of-tobacco/, accessed 14 September 2020).

[29] Big tobacco is exploiting COVID-19 to market its harmful products. Washington, D.C.: Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids; 2019 (https://www.tobaccofreekids.org/media/2020/2020_05_covid-marketing, accessed 14 September 2020).

[30] El-Awa F, Fraser CP, Adib K, Hammerich A, Abdel Latif N, Ranti Fayokun R, et al. The necessity of continuing to ban tobacco use in public places post-COVID-19. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2020;26(6):630–632.