1 / 14

Amina Aden, 28, lies alongside her child inside a cholera treatment centre in Banadir hospital in Mogadishu. She has travelled 20 km from her home in Eelasha Biyaha because she is suffering from diarrhoea. Last year, Amina’s 12-year-old daughter contracted cholera but recovered at the same centre. Cholera is endemic in Somalia but is treatable and preventable if patients receive proper and timely care. The WHO’s support of disease surveillance systems and well equipped laboratories means that Somalia is better able to detect and respond to cases like Amina’s.

Photo credits:Arete, Mogadishu, April 28, 2018

2 / 14

Khadiijo Ahmed and her 11-month-old child Abdi Mohamed wait inside at the cholera treatment centre in Banadir hospital in Mogadishu, Somalia. Khadiijo, who was forced to leave her home and now lives on the outskirts of the capital, has already lost 2 children to the disease: her daughter Sahra died aged 8 last September while Gani, aged 11, died 7 weeks ago. This second outbreak of cholera started in December last year and has been exacerbated by severe flooding that has displaced around 430 000 people throughout the country, including many who are living in temporary shelters.

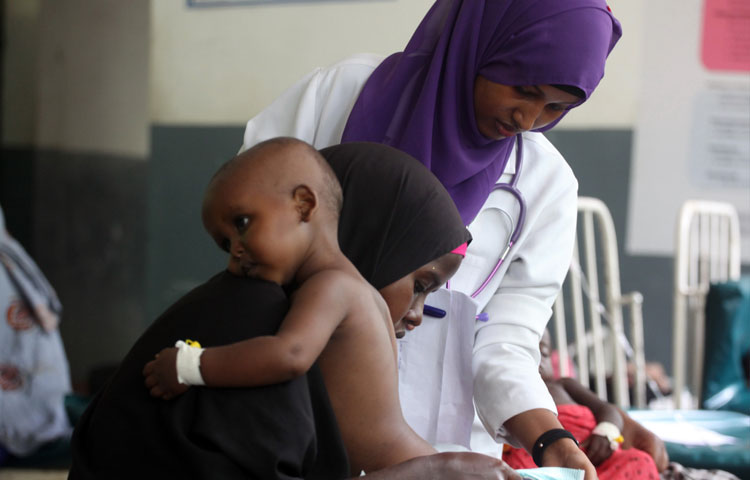

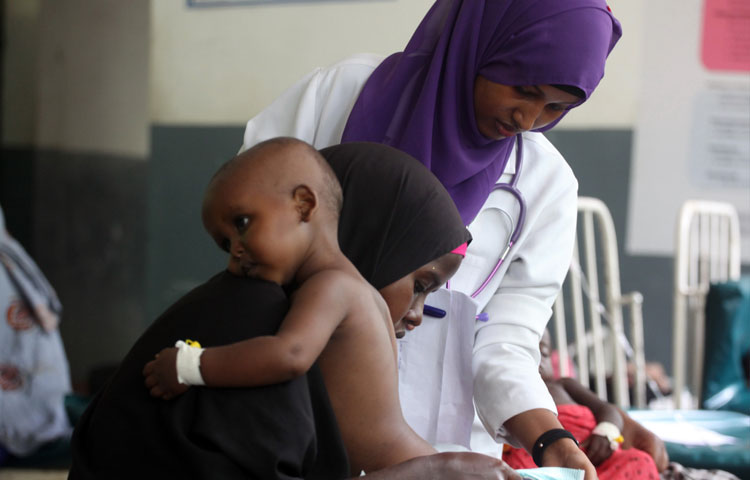

3 / 14

Khadiijo Ahmed and her 11-month-old child Abdi Mohamed are assisted by a nurse in Banadir hospital in Mogadishu. Last year’s WHO-assisted response to the cholera outbreak included training health workers, expanding health facilities, a country-wide vaccination campaign and the provision of safe water and hygiene facilities. These improvements are now being tested, with around 2300 cases of cholera being reported since last December and 9 deaths.

4 / 14

Nor Ibrahim Sabdow, 30, walks past his makeshift home at the Shimbirale camp for internally displaced people on the outskirts of Mogadishu. He survived last year’s cholera outbreak but his one-year-old daughter was killed by the disease. “I didn’t think that I would survive, but I am happy I am still alive,” he said. Among those most at risk from the new outbreak of cholera are the tens of thousands of internally displaced people who are living in temporary shelters with little access to clean water. To combat this latest outbreak, WHO has strengthened surveillance and case investigations and trained and deployed community health workers to provide basic care.

5 / 14

Women and their children wait to be vaccinated against cholera at the Banadir hospital in Mogadishu during last year’s severe outbreak. The vaccination campaign focused on hotspots in Mogadishu, Kismayo, Beledweyne, Baidoa and Jowhar. Experts travelled house to house to educate and immunize the community. The vaccines were provided by GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, and administered by the government of Somalia, the WHO, the UN children’s agency UNICEF and other bodies.

6 / 14

Health workers give children the oral cholera vaccine at the Banadir hospital in Mogadishu in March last year. The drought exacerbated the cholera outbreak because it forced vulnerable communities to use contaminated water. At the height of the crisis, up to 400 new cases were reported in one day. GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, delivered 953 000 doses of the oral vaccine to protect over 450 000 people.

7 / 14

A young boy, suffering from acute watery diarrhoea, is supported by his father in the stabilization centre for malnourished children, in Baidoa, Somalia, in February 2017. When rains failed last year, the drought exacerbated an already parlous humanitarian situation. Five million people, or 40% of the population, already did not have enough to eat, and at least 320 000 children aged under-5 were acutely malnourished. WHO is working with the Somali authorities and local nongovernmental organizations to strengthen the overall health infrastructure so that the country can deal more effectively with diseases that threaten the already vulnerable population.

8 / 14

A laboratory specialist checks stool samples for cholera at the Reference Laboratory in Mogadishu, Somalia, which is supported by WHO. Cholera cases are confirmed by testing stool samples in a laboratory. In the past, samples had to be sent to Nairobi, which could take 2 weeks. Now, thanks to WHO’s support for national reference laboratories, the process only takes 3 days.

9 / 14

A worker checks the inventory at the WHO warehouse in Mogadishu, Somalia. WHO has provided vital supplies such as reagents and testing kits. It also helped train laboratory technicians and supports laboratories in Mogadishu, Bosaso and Hargeisa.

10 / 14

A family wash their hands using clean water before eating in a settlement for people displaced by drought in Galkayo, Somalia. Lack of rain and ongoing war has meant that thousands of people have been forced into settlements like this one. Limited access to clean water means that diseases like cholera can spread quickly through the settlements.

11 / 14

Hawa Ibrahim holds her 10-year-old son Andi Nassir, who was suffering from acute watery diarrhoea, in the stabilization centre for malnourished children, in Baidoa during last year’s cholera outbreak.

12 / 14

Ahead Isaak Mohamed sits with her child, who is being treated for cholera at Banadir hospital in Mogadishu in 2017. She had already lost 2 children to the disease: Sharifo, 7, died in early March and Mohamed, 10, died just 3 days before the photograph was taken. The family were forced to flee their home in Baidoa after they lost all their livestock to the drought and were living in a displaced persons’ camp in Mogadishu.

13 / 14

A mother holds her child's hand while receiving rehydration fluids, at the cholera treatment centre in Banadir Hospital, Mogadishu.

14 / 14

Ali Hassan Mohamed Hassan, 38, holds his 6-month-old son, Mohamed Hassan Mohamed, at the cholera treatment centre in Banadir hospital in Mogadishu. After losing his livestock to drought and fleeing his home in Lower Shabelle, Ali walked with his family to Mogadishu to seek help. Ali lost his leg years ago in a roadside bomb.

❮ ❯