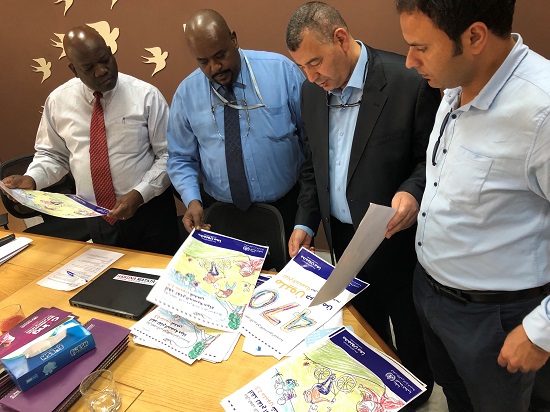

WHO works with Libya's Ministry of Health to create awareness-raising materials about the importance of vaccination.

WHO works with Libya's Ministry of Health to create awareness-raising materials about the importance of vaccination.

In early 2019, when a seriously ill one-year-old boy arrived at his hospital in Tripoli, Dr Hamza Khalifa saw that his sickness was more than a common cold. “His mother’s concern was his high fever. He was really unwell,” says Dr Khalifa. But seeing a skin rash, and knowing the other symptoms to look for, Dr Khalifa diagnosed measles.

“We isolated him and gave him anti-fever medication and fluids,” until the little boy recovered, says Dr Khalifa. “If you treat the symptoms well, you can save the child.”

For more than a decade, Dr Khalifa has been part of a network in Libya to monitor Acute Flaccid Paralysis (AFP), the type of paralysis that, in rare cases, may indicate polio. As a pediatrician, he also knows the signs of measles.

A WHO workshop in late August 2019 sought to build on the expertise of Libyan doctors like Khalifa, combining their experience with polio and measles--two diseases that can spread rapidly and harm children. Thankfully, Libya has been polio-free since 1991, but migration into the country means that health providers cannot be complacent. Measles has not been common in Libya, but has flared up at times. Instability in the country has made it difficult, in some areas, for parents to have their children vaccinated.

Trained clinicians have already been carefully keeping track of paralysis cases. Others have followed or responded to measles outbreaks. At the workshop, they refreshed their knowledge of how to track both of these dangerous diseases, using a data-collection system that feeds into a country-wide database.

“I’ve been working in AFP since 2006--I have experience,” says Dr Khalifa. “But for me, adding the surveillance component of measles was good.” He not only treats individual cases, but contributes to an information network that tracks disease patterns.

Dr Abdulrahim Ali Sheba, a doctor in the southern Libyan area of Al Shatti, became more familiar with polio/AFP surveillance procedures. “Three years ago when I saw a case of AFP, I let it go. I didn’t collect samples. I didn’t think it would be polio,” he says. “Now I follow up.”

Libya’s doctors are working in difficult conditions. The country is facing armed conflict, fuel shortages, access restrictions, and many other challenges that directly affect health services. Despite this, “Libya’s Ministry of Health is fully committed to protecting children,” says Elizabeth Hoff, WHO Representative in Libya. “Health staff are collecting information and samples on the ground. They’ve been able to detect and respond to measles outbreaks, and they are producing a monthly surveillance report that can guide the response.”

Dr Khalifa appreciates that the workshop strengthened the surveillance network’s ability to track both diseases: measles and polio. The training “is improving our diagnoses and helping us catch the cases,” he says.

Led by the Ministry of Health, with support from WHO, Libya’s doctors are working to keep children safe and healthy. They have one enormous advantage: "Parents in Libya will struggle to get their children vaccinated,” says Dr Khalifa. “I myself, I drove 80 kilometres to get my child vaccinated.

“The population knows how important vaccination is.”