WHO and KSrelief sign US$ 9.5 million agreement to support Yemen’s health system

29 May 2024, Aden, Yemen – Nearly US$ 9.5 million in funding has been secured for critical health projects in Yemen – a pivotal step in strengthening the country’s health system. WHO signed the significant agreement with the King Salman Humanitarian Aid and Relief Centre (KSrelief) at the opening of the Seventy-seventh World Health Assembly in Geneva, Switzerland.

29 May 2024, Aden, Yemen – Nearly US$ 9.5 million in funding has been secured for critical health projects in Yemen – a pivotal step in strengthening the country’s health system. WHO signed the significant agreement with the King Salman Humanitarian Aid and Relief Centre (KSrelief) at the opening of the Seventy-seventh World Health Assembly in Geneva, Switzerland.

The projects funded under the agreement will target 12.6 million people in Yemen across various governorates. Projects will focus on improving access to safe water, preventing the spread of infectious diseases and enhancing the health system’s capacity to respond to outbreaks. These efforts are expected to significantly reduce morbidity and mortality rates and enhance the overall resilience of Yemen’s health infrastructure.

The agreement reflects the ongoing commitment by WHO and KSrelief to address Yemen’s pressing health needs. It was signed by Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General, and His Excellency Dr Abdullah Al Rabeeah, Supervisor General of KSrelief, in the presence of Dr Hanan Balkhy, WHO Regional Director for the Eastern Mediterranean.

“This agreement signifies a strong partnership and a shared vision for a healthier future for Yemen,” said Dr Arturo Pesigan, WHO Representative to Yemen. “The funding from KSrelief will be invaluable in strengthening our efforts in water, sanitation and hygiene services; acute watery diarrhea response; and measles surveillance and response. This funding will make a substantial difference to the lives of those people most in need.”

Mr. Saleh Al-Theebani, Director of KSrelief's Aden branch, appreciated the partnership between KSrelief and WHO aimed at providing life-saving interventions for the Yemeni people. He emphasized that this new funding is part of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia's ongoing support to alleviate suffering and ensure access to essential health services across the country

KSrelief has been a steadfast supporter of Yemen for years, providing vital resources and expertise to address the country’s health challenges. Through its cumulative contribution of US$ 320 million to WHO, KSrelief has played a key role in supporting humanitarian and health response operations in Yemen.

Media contacts

WHO Yemen Communications

Email:

About WHO

Since 1948, the World Health Organization (WHO) has been the United Nations agency dedicated to advancing health for all, so that everyone, everywhere can attain the highest level of health. WHO leads global efforts to expand universal health coverage, direct and coordinate the world’s responses to health emergencies and connect nations, partners and people to promote health, keep the world safe and serve the vulnerable.

About KSrelief

The King Salman Humanitarian Aid and Relief Centre (KSrelief) is a humanitarian aid organization established by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. KSrelief is dedicated to coordinating and providing international relief to alleviate suffering and provide essential services to those in need.

Invest, implement and innovate to reduce Yemen’s malaria burden

Entomological surveillance workshop for malaria in Socotra. Photo credit: M. Al Amoody 25 April 2024, Socotra Island and Tehama region, Yemen – Despite persistent efforts to prevent and control malaria in Yemen, about two thirds of the population remain at risk of the disease.

Entomological surveillance workshop for malaria in Socotra. Photo credit: M. Al Amoody 25 April 2024, Socotra Island and Tehama region, Yemen – Despite persistent efforts to prevent and control malaria in Yemen, about two thirds of the population remain at risk of the disease.

With World Bank support via the Emergency Human Capital Project (EHCP), WHO implements key interventions to deliver a tailored approach to malaria management at country level in line with the burden of disease. This includes capacity-building for malaria focal points and the rollout of indoor residual spraying campaigns for affected communities and those at risk.

WHO supported an indoor residual spraying campaign in the Tehama region, to cover Yemen’s 2310 highest malaria-burden neighbourhoods, in February 2024. The campaign directly protects more than 540 000 people from malaria and dengue, across 86 000 homes sprayed. It also indirectly protects more than 2 million people in targeted and neighbouring districts.

More than 780 spraying workers, 160 team leaders and 93 field supervisors carried out the campaign. This intervention builds on the last spraying campaign conducted by WHO under EHCP in the same region in November and December 2022.

Some areas of the country, such as Socotra Island, have made tremendous progress, and are working towards the goal of having no local malaria transmission. Socotra started working towards malaria elimination in 2000, with no local cases reported since 2005.

In March 2023, WHO conducted a pre-elimination assessment on the island, in line with WHO guidelines to identify any gaps and boost readiness in case malaria is imported from other parts of the country or abroad. This is a particular risk due to the frequency of tropical cyclones affecting Socotra, as well as the impacts of climate change and the humanitarian situation in Yemen and nearby countries.

> Following this assessment, a training of trainers session was conducted, in February 2024, for 20 malaria staff from Hadhramaut, Marib and Socotra governorates. This sought to enhance their skills in surveillance, diagnosis, case management and vector control.

Following this assessment, a training of trainers session was conducted, in February 2024, for 20 malaria staff from Hadhramaut, Marib and Socotra governorates. This sought to enhance their skills in surveillance, diagnosis, case management and vector control.

Soon after the training, in Socotra, reports were received of an imported suspected malaria case. The trained staff moved quickly to implement active case detection – based on the protocol learned at the session – including clinical diagnosis, rapid diagnostic testing, and laboratory confirmation. The case tested positive, having recently travelled to Socotra from Hudaydah, a high-burden governorate. The individual was provided a course of treatment and was followed up until fully recovered.

Preliminary results of one such innovation, an assessment of climate-related risks of malaria and other climate-sensitive diseases, are expected to be available in June 2024. This crucial information will contribute to the continuation of evidence-informed action to tackle malaria in Yemen.

Related links

Stopping polio in Yemen, one step at a time

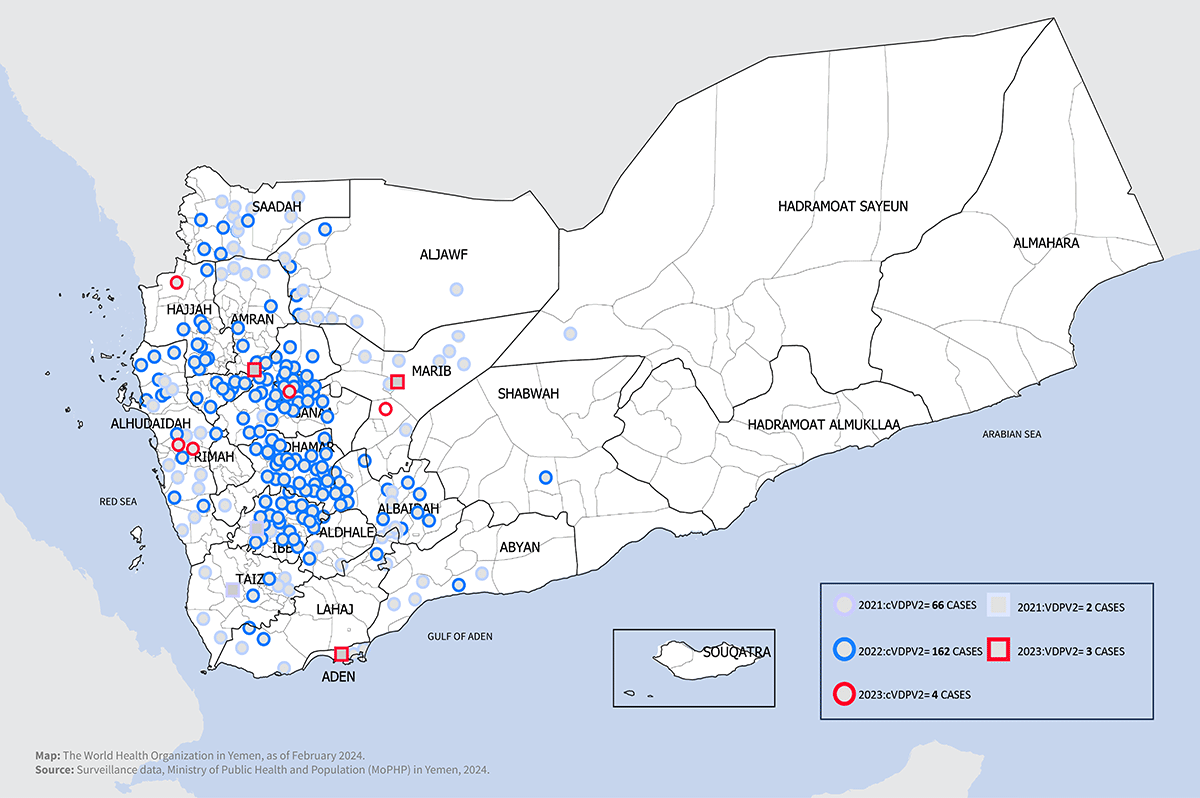

25 April 2024 – As long as a single child is infected with polio, all unvaccinated children are at risk of contracting the disease. In fragile and conflict-affected contexts, such as Yemen, children can be especially vulnerable. From 2021 to 2023, Yemen reported 237 variant poliovirus type 2 cases – from both circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) and vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (VDPV2).

25 April 2024 – As long as a single child is infected with polio, all unvaccinated children are at risk of contracting the disease. In fragile and conflict-affected contexts, such as Yemen, children can be especially vulnerable. From 2021 to 2023, Yemen reported 237 variant poliovirus type 2 cases – from both circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2) and vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (VDPV2).

“We didn’t know we were supposed to take [our children] to the hospital to get vaccinated, and I wasn’t aware of the seriousness of these diseases or thinking that any of my children would get sick,” said a mother whose child contracted polio in 2021 and is now paralysed.

One in 4 children in Yemen cannot receive all the recommended vaccinations on the national routine immunization schedule. Indeed, 17% of Yemen’s children are considered zero-dose children – they have received no doses of vaccine. Low vaccination coverage, and increased vaccine hesitancy among parents are among the many factors that contribute to this situation.

Early on 25 February 2024, about 6700 fixed and mobile vaccination teams set out to reach nearly 1.3 million children aged under 5 years with the novel oral polio vaccine type 2 (nOPV2). Working from health facilities and on the streets of the 12 target governorates, the teams were determined to give children the 2 drops of vaccine needed to protect them from the debilitating disease.

Fig. 1. Geographic distribution of laboratory-confirmed variant poliovirus type 2 cases (2021–2023)

Disclaimer: The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

Disclaimer: The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries.

Carrying vaccine coolers, the vaccination teams travelled the roads of the targeted cities, their crumbling alleys a sign of the decade of conflict that has affected Yemen. Some areas were easy to access, but others involved arduous journeys to reach vulnerable children.

On the outskirts of cities, congested camps of internally displaced people reflect the impact of the protracted conflict. Dwellings are made of boards and old rugs, and access to safe water, sanitation and hygiene is lacking. Many of the families in the camps once had settled homes; their future is now uncertain.

Mobile vaccination teams find many deprived children as they go door to door, but sometimes the biggest challenge is to convince parents to vaccinate their children. Parents and caregivers are usually positive when teams approach them. But there is increased vaccine hesitancy and refusal among families affected by misinformation coupled with limited health literacy. This has left many children unprotected.

There is no cure for polio; it can only be prevented. The impacts of the conflict and adverse socioeconomic conditions have left many children in Yemen susceptible to the disease.

There is no cure for polio; it can only be prevented. The impacts of the conflict and adverse socioeconomic conditions have left many children in Yemen susceptible to the disease.

It is only thanks to parents who wait in long lines at health facilities and vaccination teams who travel long distances to vaccinate children that Yemen’s polio outbreak is not more widespread.

Yemen's Ministry of Public Health and Population carried out the polio immunization activities as part of a national immunization campaign funded by the Global Polio Eradication Initiative and supported by WHO and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF).

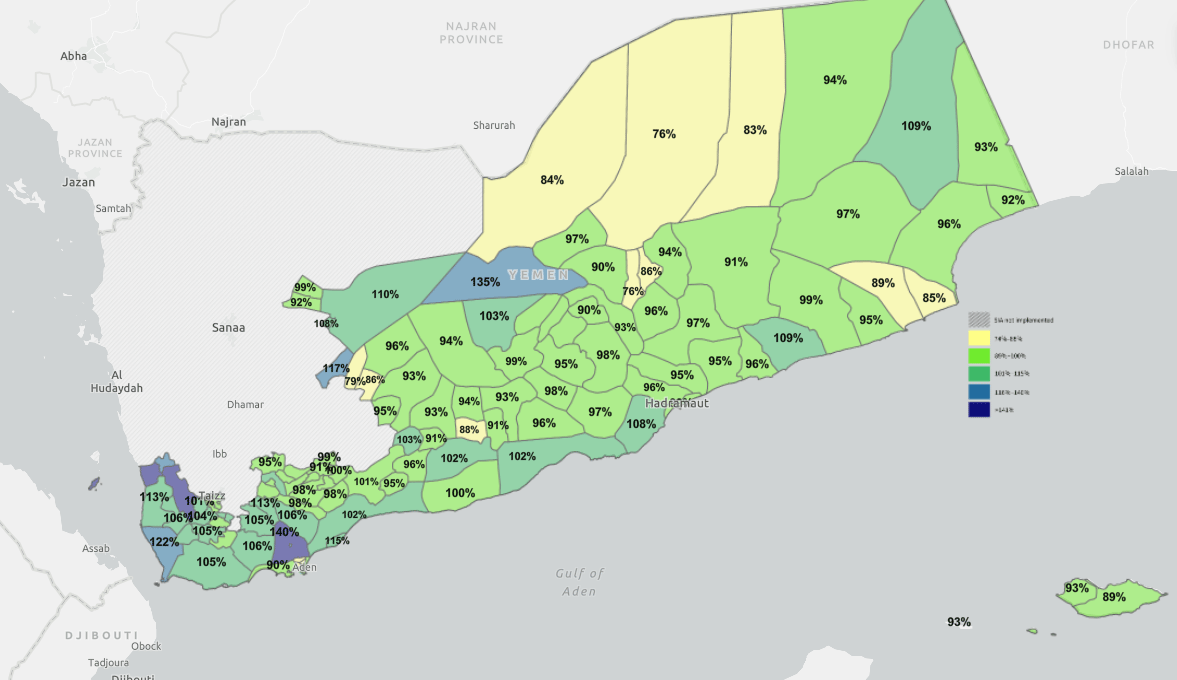

In total, the campaign reached 1.29 million vulnerable children across the 12 governorates. Teams delivered the polio vaccine to the doorstep of every home, shelter and camp in fragile communities to protect children’s health and future. The independent post-campaign monitoring data show that 91% of targeted children were reached during the supplementary immunization activity, with coverage by governorate ranging from 86% to 99%. Refusal was the main reason for children missed during the campaign.

Fig. 2. Immunization coverage rate in targeted governorates (25–28 February 2024)

Multiple doses of polio vaccine offer the best protection to children, especially those living in fragile and conflict-affected settings. The Ministry, WHO and partners will take the lessons learned from this campaign and work with health workers to deliver another vital round of polio vaccine to these same communities in the coming months.

“People saw the deadly impact of diseases with their own eyes, so they would come to get vaccinated”

the Ministry of Public Health and Population25 April 2024 – Interview with Dr Mohammed Hajar, Advisor on Immunization to the Ministry of Public Health and Population, and one of the greatest minds behind the Essential Programme on Immunization (EPI) in Yemen.

the Ministry of Public Health and Population25 April 2024 – Interview with Dr Mohammed Hajar, Advisor on Immunization to the Ministry of Public Health and Population, and one of the greatest minds behind the Essential Programme on Immunization (EPI) in Yemen.

“I only came to this interview because EPI is one of my grandchildren.” These were the very first words uttered by Dr Mohamed Hajar, a man in his late seventies, as he entered the office for the interview.

“In Yemen, from 1970 to 1976, there was only the smallpox vaccine and field teams working to cover the governorates,” he went on. “But in 1977, the national Expanded Immunization Programme was established, and included basic vaccines, namely diphtheria, whooping cough, poliomyelitis, measles, tuberculosis, and tetanus for women. We started in only 3 governorates: Sana’a, Taiz and Hodeidah, because they had adequate roads and electricity.”

Before EPI, vaccinations were only provided through foreign teams such as the Peace Corps, Save the Children, a Norwegian group in Ibb governorate and a Swedish group in Taiz – all of which would provide people with vaccines without the administration of any national programme. But when EPI began, these international initiatives were introduced within its framework, and they were provided with EPI vaccines and associated forms. Immunization focal points under the supervision of the Ministry of Public Health and Population then followed up on coverage in each governorate.

Coverage was confined to these 3 governorates until the primary health care and immunization programmes were integrated in 1982. As a result, care units were expanded across Yemen’s governorates. Most units had a vaccination officer and a health worker, which increased immunization coverage. This also helped revitalize the primary health care programme, as demand for immunization was greater than for primary health care services.

Dr Hajar continued to recount the history of EPI: “In 2004, the second dose of the rubella vaccine was approved, while in 2005 the pentavalent vaccine [combined diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine, hepatitis B and Haemophilus influenzae vaccine] was introduced, having a significant impact in mitigating the incidence of these diseases. But one of the most important achievements was in 2009, when Yemen was declared free of the wild poliovirus. There has been no trace of the virus since 2006.”

Integrated efforts continued to strengthen the national EPI with new and improved vaccines, reducing the spread of the targeted viruses in Yemen. Vaccine preservation systems have also been strengthened, with cold chain systems a vital component. About 15 cold rooms, along with many refrigerators and coolers, have been added, and transport mechanisms enhanced at all subnational levels.

Manuals were developed and teams trained to help share knowledge and improve performance. All relevant documents were also provided, including records, children and women’s cards, and templates for daily and monthly reports from the subdistrict level to central level.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, polio immunization was carried out from fixed locations. In 2004, the strategy switched to house-to-house campaigns to ensure full coverage of all children aged under 5 years in all locations, including remote areas. This strategy continued until 2021, when the polio vaccine was confined to fixed sites in many areas in Yemen.

For decades, Yemen has promoted efforts that serve the health and well-being of its people, but the ongoing conflict has reversed all national gains and has paralysed development. Today, Yemen is witnessing the highest levels of health risks anywhere in the world, with a significant increase in the emergence of epidemics such as cholera, measles, diphtheria, dengue and polio. Public health infrastructure and services are limited, safe water sources are scarce, and vaccine hesitancy and refusal have increased.

“Previously, people saw the deadly impact of diseases with their own eyes, so they would come to get vaccinated,” explained Dr Hajar. “People had bitter experiences of smallpox, where those who were not vaccinated were either deformed or died; measles was when a child was either blinded or died, in most cases. When measles cases started, the uptake for vaccination was very high in all centres. People had an awareness of the importance of the vaccine and that it could save lives.”

He went on to share the situation now: “Yesterday I went to one of the fixed immunization sites. The workers were there to provide the vaccine, the vaccine is available, and all the means of recording and follow-up are available, but there are no families who are about to be vaccinated.”

Initially called the Expanded Programme on Immunization, this WHO initiative – which celebrates its 50th anniversary this week – is now known as the Essential Programme on Immunization. For about 47 years, Yemen has worked with WHO, various governments, local councils, international organizations and global initiatives to build its national EPI from nothing.

These partnerships continue to underpin Yemen’s immunization efforts to reach and protect children from vaccine-preventable deadly childhood diseases. And continuing these strong partnerships is the only way that Yemen can recover from the effects of conflict and protect the future of its children.