WHO and European Union unite to fight a common enemy to humanity

Mogadishu, 7 May, 2020 – The WHO country office and the Delegation of the European Union (EU) to Somalia have joined hands under a new collaboration in the country to strengthen operational response activities for COVID-19. The new collaboration aims to accelerate support for the frontline work of WHO in combating COVID-19 in a seemingly vast country where transportation of vital medical supplies and personnel needed for rapid response to the outbreak remain a perpetual challenge owing to suspension of commercial and cargo flights and the lockdown, which has cut off the capital city from rest of the country.

In this challenging and testing time, WHO has been offered EU flights to airlift critical medical equipment and supplies from Mogadishu to its final destination in Kismayo, the capital of Jubaland state. The equipment and supplies were urgently needed in the state for its isolation centre and the transportation of COVID-19 samples collected from suspected patients.

On the morning of 3 May, the flight picked up and transported 750 kgs of vital hospital supplies and medical equipment, including emergency medicines for patient treatment, from Mogadishu to Kismayo. These supplies and medicines are part of the Interagency Emergency Health Kit (IEHK), which provides essential health care in emergency settings for up to 10 000 people over a 3-month period. Due to the intense medical needs of patients affected by COVID-19, these vital medical supplies, and in particular, the medicines airlifted for treatment of acute respiratory diseases will be used to treat up to 600 COVID-19 patients in Kismayo’s Max Falka isolation facility, which will be opened in the coming week.

On return, the EU flight also picked up 29 samples from suspected cases of COVID-19 in Kismayo and before returning to Mogadishu, the EU flight also collected another 20 COVID-19 samples from Hargeisa, Somaliland. The EU flight then returned to Nairobi and all the 49 samples were handed over to WHO in Nairobi for sending these samples to the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) for testing.

In the current race to limit further spread of COVID-19 in Somalia, the EU’s generous support has helped make an important difference in ensuring that suspected cases are tested rapidly and the public health measures are applied quickly thereby preventing transmission in the community. The EU’s support in transporting vital medical equipment and supplies for treatment of COVID-19 patients will ensure that no patient dies of COVID-19 because of lack of critical medical supplies in hospitals in any part of the country.

This new collaboration between the EU and WHO in Somalia is the result of a recently established bilateral coordination mechanism for COVID-19 response, whereby the EU is, inter alia, providing logistical and flight support to WHO for transportation of critical equipment and medical supplies, shipment of COVID-19 samples and personnel in this time of locked down while WHO is providing technical support and advice to the European Delegation for COVID-19 related activities, such as risk communications and awareness-raising initiatives in the country, which are supported by the EU. The collaboration will ensure, on one hand, the vital medical supplies reach the front lines to shield medical workers and save lives, and on the other hand, will ensure that the EU-supported activities, which are mostly implemented by the NGOs and regional health authorities, align with WHO’s strategic priorities for COVID-19 response. The European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operation (ECHO) of the European Delegation has also contributed funding support to respond to the emergency response appeal of the country office for its work on COVID-19.

Commenting on this successful collaboration, Dr Mamunur Rahman Malik, WHO Representative said “We have started a new collaboration with EU in this country as we continue to fight hard with a common enemy which is affecting humanity at greater speed than ever. The scale of this crisis demands an extraordinary response, a response that is bigger than the magnitude of this crisis. This coordination and solidarity at national level proves that we all need to stick together to get over this crisis together. We are not safe until everyone is safe”.

The new partnership between WHO and the EU delegation will help increase resilience to reduce the health and social impact of COVID-19 and all other future health emergencies in the country by protecting the vulnerable and keeping the country safe.

Somalia’s polio teams help combat COVID-19

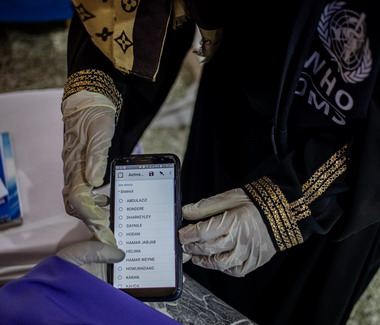

In Somalia, staff and volunteers from the country’s long-running polio programme have been trained to detect COVID-19 cases. Here, a trainee learns how to use a COVID-19 tracking database on her phone.4 May 2020 – “The road to the mountain village was rough. It’s only 50 kilometres, but it took more than 3 hours,” says Dr Fatima Ismail, a disease surveillance officer working in Somaliland. “We were bouncing in the car.”

In Somalia, staff and volunteers from the country’s long-running polio programme have been trained to detect COVID-19 cases. Here, a trainee learns how to use a COVID-19 tracking database on her phone.4 May 2020 – “The road to the mountain village was rough. It’s only 50 kilometres, but it took more than 3 hours,” says Dr Fatima Ismail, a disease surveillance officer working in Somaliland. “We were bouncing in the car.”

In early 2020, Dr Fatima’s team headed to a remote village near Djibouti to check on a small boy. The boy’s right arm and leg showed a kind of paralysis that sometimes indicates polio. “The village polio volunteer in this mountainous area, geographically inaccessible, found an acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) case,” Dr Fatima remembers.

When children show signs of this paralysis, it’s critical to get stool samples to a laboratory to determine whether they have polio. Polio teams ride camels in the desert or donkeys in the mountains when they have to. They brave bombs to get samples out of conflict zones to laboratories. In brutally hot climates, they plug mini-freezers into car dashboards to keep samples cool.

All over the world, polio surveillance systems that have been built up over decades track infection sources, evaluate symptoms and transport samples to the laboratory — despite distance, natural disasters, and sometimes war. Now, this network of disease surveillance — reaching into the most far-flung corners of the globe — is being tapped to address the COVID-19 pandemic.

“In Somalia, the polio programme pivoted its workforce of thousands of frontline staff to support the effort as the cases of COVID-19 spread. Rapid response teams — made up of disease surveillance officers, community health care workers and volunteers — were trained to educate people about the virus and to test suspected cases. By April 2020, the teams were deployed in the field,” said Dr Mamunur Malik, WHO Representative in Somalia.

"In Somalia’s remote villages, they know us as their polio teams, and once they see us, what comes to their minds is that we’re giving them information about polio,” says Mohamed*, a surveillance officer. “So we also give them information about COVID-19. Social mobilisers tell them about COVID-19 symptoms, how to prevent getting infected, physical distancing, cleaning their hands very well with running water and soap.”

The careful procedures that the teams learned for polio surveillance have been adapted for COVID-19, where the required sample is a naso-pharyngeal swab. “We’ve trained our surveillance people on the case definition and how to collect the samples correctly, from cases that meet the case definition of a suspected case of COVID-19,” says Dr Fatima. “It’s the same infrastructure. After, when we collect the samples from the patient, we send it to the laboratory in Hargeisa.”WHO has given the laboratory equipment and supplies to test samples for COVID-19".

"As with polio samples, the samples of COVID-19 have to be refrigerated, the ice packs should be VERY cold,” says Mohamed. Teams are used to monitoring the packs’ temperature, even in Somalia’s hot weather.

“The logistical challenges we face with AFP/polio surveillance are still the same. This is the rainy season and the roads tend to be terrible,” says Mohamed. “You can’t get to certain places you normally get to, because of the situation on the road. Most of our vehicles can’t make it through the mud.” In those situations, teams work with other United Nations agencies to arrange special humanitarian flights to ship samples.

Frontline staff put their own lives on the line. In April 2020, the polio team lost a colleague due to COVID-19-related infection. Ibrahim Elmi Mohamed, who joined WHO in 2001, was working as a district polio officer in Lower Shabelle. His tragic death, one of many frontline staff around the world due to COVID-19, reminds us of the risks they face every day they go to work.

“Despite overwhelming challenges, teams are committed to continuing their polio work in tandem with the COVID-19 response. It is critical that polio surveillance continues during the pandemic, as Somalia is also fighting outbreaks of vaccine-derived polio type 2 and 3. With polio vaccination campaigns temporarily paused, the teams must be able to track any resulting spread of poliovirus and get ready to respond as soon as it is safe to do so,” says Dr Malik.

“All of us are still doing polio surveillance at the same time as we do surveillance for COVID-19," says Dr Fatima. “I used to hear from my colleagues that the polio surveillance system is the strongest disease surveillance system. Any polio surveillance team can work in the detection of COVID-19 cases because of the system’s structure, the capacity and experience of the teams.”

Mohamed agrees. “My surveillance coordinator said don’t leave the AFP surveillance behind, follow that normal routine, don’t forget it and leave it aside.’”

As Somalia grapples with the COVID-19 pandemic, its trained teams are working quickly to prevent the spread of both COVID-19 and polioviruses. “What gives me hope in the COVID-19 response is when I look behind and I see what we have done with the polio teams, the impact we’ve had on so many lives,” says Mohamed. “We face everything and we overcome it.”

*Family name withheld for security reasons

WHO provides support to increase testing capacity for COVID-19 to limit community transmission

As the COVID-19 pandemic escalates the WHO country office has helped Somalia rapidly build and scale up the testing capacity for COVID-19 in Somalia.

As the COVID-19 pandemic escalates the WHO country office has helped Somalia rapidly build and scale up the testing capacity for COVID-19 in Somalia.

In March 2020, when the country’s first case of COVID-19 was laboratory-confirmed in Somalia, the country had no capacity for testing and diagnosis of COVID-19. WHO sent nasopharyngeal swab from 4 returnee travellers, all Somali citizens, to Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) in Nairobi which has an accredited Biosafety Level-2 (BSL-2) laboratory for viral and emerging pathogens supported by WHO and the United States Centers for Disease Prevention and Control. On 16 March, WHO received the laboratory test result of these 4 samples, of which one tested positive. This was the first reported case of COVID-19 in Somalia which was travel-associated.

The Ministry of Health and Human Services of the Federal Government of Somalia officially confirmed the first COVID-19 case in Somalia immediately after the test result was officially communicated by WHO to the Ministry.

Building testing capacity

Since then the WHO country office has shipped over 150 samples collected from different parts of the country to KEMRI and many of them have tested positive. Considering that the country would need to build its testing capacity rapidly for COVID-19 and decentralize laboratory testing in order to rapidly isolate and treat cases while tracking close contacts in line with WHO’s strategy to “Test, track and treat” for detecting and preventing community transmission, 3 laboratories with molecular testing facility were rapidly established by WHO in April with the financial support from the Italian Development Cooperation. These laboratories were established in Mogadishu, Garowe and Hargeisa.

Partner support

This work truly reflected the global action and the power of solidarity for defeating our common enemy – COVID-19 – in one of the most fragile and vulnerable settings of Africa, a country which has been experiencing protracted conflict and political instability weakening the health system. While funds for purchase of molecular testing machine, the real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) for equipping the 3 laboratories was provided by the Italian Development Cooperation, the machines were air-lifted by the United Nations Humanitarian Air Services (UNHAS) operated by the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) directly from Nairobi to Mogadishu, Garowe and Hargeisa. The WHO country office funded the establishment of these laboratories, including ensuring biosafety practices, buying essential supplies, conducting training and providing molecular diagnostic assays to kick-start testing. The detection of COVID-19 with nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT), such as RT-PCR is regarded as the ‘gold standard”.

On 9 April 2020, just 2 days after the world celebrated World Health Day acknowledging the contribution of nurses, midwives and other health workforce, the RT-PCR machine was handed over to Ministry of Health officials at the public health laboratory of Mogadishu by Dr Mamunur Rahman Malik, WHO Representative for Somalia. While thanking the Italian Development Cooperation for their support, Dr Malik commented “It is a testing moment for the world to come together to save lives and fight a common threat to our humanity. We thank our important partner the Italian Development Cooperation for their generous contribution to establish 3 functioning laboratories for testing of COVID-19. We also thank WFP for air-lifting the RT-PCR machine and other supplies from Nairobi to different locations in Somalia barring the lockdown and flight suspension in and out of Somalia”.

On 9 April 2020, just 2 days after the world celebrated World Health Day acknowledging the contribution of nurses, midwives and other health workforce, the RT-PCR machine was handed over to Ministry of Health officials at the public health laboratory of Mogadishu by Dr Mamunur Rahman Malik, WHO Representative for Somalia. While thanking the Italian Development Cooperation for their support, Dr Malik commented “It is a testing moment for the world to come together to save lives and fight a common threat to our humanity. We thank our important partner the Italian Development Cooperation for their generous contribution to establish 3 functioning laboratories for testing of COVID-19. We also thank WFP for air-lifting the RT-PCR machine and other supplies from Nairobi to different locations in Somalia barring the lockdown and flight suspension in and out of Somalia”.

César V. Arroyo, Country Director and Representative of WFP Somalia said “We won’t stop until we can stop this virus. We are commited to working together to getting the vital medical supplies to front lines to attack this virus on all fronts. We must stand up to save humanity. We need action from all and for all.”

The public health laboratories play a critical role in surveillance especially in case detection and case finding. Diagnostic testing for COVID-19 is critical to tracking the virus, and delaying and suppressing viral transmission. This is particularly important for Somalia as reducing transmission will reduce the burden on the fragile health systems in a country which has been chronically weakened due to protracted emergencies, under-investment and neglect.

Scaling up the public health response

While the virus was slow to reach the country compared to other parts of the world, case counts are growing rapidly every day in recent weeks and the virus continues to spread. Cases have also been reported and confirmed in remote areas. While WHO continues to work with the local health authorities in Somalia to scale up its public health response to ongoing transmission, establishment of 3 laboratories and scaling up its molecular testing capability is part of the strategy for decentralized testing across the country which will not only ramp up testing but ensure rapid identification of cases, the tracking down and quarantining of contacts and the isolation and treatment of patients as part of systematic strategy for containment.

In this interconnected world, we are only as strong as the weakest health systems. The current public health crisis is not the first and will not be the last. Recovery from this crisis of unprecedented scale must lead to building a better and resilient public health system in Somalia. Establishment of the public health laboratories with molecular testing capability which are decentralized will be an investment worthy of rebuilding a resilient health system in the country for control of any other emerging pathogens, including any novel respiratory pathogens in the future.

Related links

EWARN increases surveillance for COVID-19

23 April 2020 – In Somalia's COVID-19 response, being ahead of the curve is the only way to stop transmission and limit spread of the virus in the community. Enhancing active surveillance and expanding its geographic coverage to include both the private and public sector using a syndromic-based approach is the best way to detect cases early.

In Somalia, in the absence of any routine disease surveillance system, EWARN is doing what it was intended to do and what the system did best in other outbreak situations.

EWARN, a disease surveillance system for epidemic-prone disease, was initially launched in Somalia in 2008 but due to operational difficulties was halted only to be reactivated by WHO together with federal and state health authorities in 2017 as a real-time password protected web-based electronic surveillance system. This reactivation came after one of the worst cholera outbreaks in Somalia in the past decade when there was no reliable disease surveillance system in the country to monitor, detect and respond to the cholera outbreak and other epidemic-prone diseases and health threats.

By 2019, an estimated 6.5 million people, including 2 million internally displaced people, were covered by the EWARN system. Currently, 535 out of 1075 health facilities across the country are covered by EWARN; 64% of these facilities submit their EWARN reports on time and 74% of the reports are complete. In 2019 alone, 74 new health facilities were added to the EWARN system. A record 4 789 832 consultations were reported in 2019 through the EWARN system. Knowledge of patient consultations and population coverage helps WHO and other health partners to measure the consultation rate and identify gaps in health care access in vulnerable populations. In 2019, the system triggered over 18 000 outbreak alerts, of which 883 were verified through field investigation by WHO and the health authorities.

In a country like Somalia which has a fragile health system, EWARN has been able to detect and prevent epidemics in real time in drought-affected districts, camps for internally displaced people in different states, including their host communities, and districts inaccessible to humanitarian agencies or the government. As the system relies on electronic data collection using a mobile phone-based application data on epidemic-prone diseases can be regularly collected and collated, even from insecure and inaccessible areas of the country, This would not have been possible if EWARN relied on a paper-based system for data collection.

As the country grapples with increased transmission of COVID-19, the EWARN system has been rolled out to another 200 health facilities, including all privately owned medical facilities which are admitting and treating patients with acute respiratory diseases of unknown origin. Using online training platforms adapted to the country need and context, the WHO country office through its Public Health Emergency Officers is conducting training at each of these newly enroled health facilities, including the private sector hospitals on use of syndromic case definition for COVID-19 and early recognition and reporting of suspected case. The training also includes data entry and reporting using both the web-based application and mobile platform of the EWARN system. In addition to 14 epidemic-prone diseases that are already included in the system (e.g. waterborne, vaccine-preventable, vector-borne and mixed transmission diseases), the case definition for COVID-19 has been added as the newly reportable health condition in the EWARN as part of roll out.

Event-based surveillance

Another important innovation for the EWARN roll out during this period of COVID-19 has been the addition of event-based surveillance system which is intended to capture non-specific and other respiratory diseases of unknown origin in the EWARN for triggering alert and appropriate investigation.

Understanding the evolution and transmission dynamics of any epidemic remains a challenge even in countries with good health system and functioning surveillance system. Somalia, a country with fragile health systems and with no routine disease surveillance system, the challenges are immense and overwhelming. The EWARN data on COVID-19 cases (either suspected or confirmed) will provide a snapshot of epidemic size, geographic spread and stages which is important for understanding and analyzing the effectiveness of response strategies for containment and suppression of the virus.

The other main advantage of EWARN being rolled out for COVID-19 is the use of its GPS coordinates which will allow alerts of the location of a suspected case or event of a cluster of cases to be precisely pinpointed and automatically displayed on the electronic dashboard. This will eventually help in efficient contact tracing and identifying more suspected cases in the vicinity of the alert of this event or a spectacled case.

Since the EWARN system is supported by a mobile app linked to its web-based platform, local health workers in inaccessible areas will also be able to use the app to submit real-time data on COVID-19 electronically thus overcoming security and geographic barriers.

As the roll out begins, a weekly bulletin will also be generated automatically from the system, which will show all alerts but also distilled for COVID-19 by health facility and geographic location.

The EWARN surveillance system continues to transform the way Somalia detects an epidemic disease including the COVID-19 in the absence of any routine disease surveillance system in a very complex setting. In addition, to disease detection and monitoring, the data generated from EWARN for COVID-19 will be useful for understanding the burden and help to prioritize, plan, implement and monitor the health emergency response in the country. Like what has been done in the past, the EWARN continues to keep the country safe and protect the vulnerable by early detection and response to epidemic threats posed by COVID-19 in the country. The success and experience of EWARN, as an early warning disease surveillance system during this period of COVID-19 will be useful for other emerging health threats as the country transitions from a state of protracted crisis to early recovery and development. The current work of WHO country office in responding to COVID-19 is also a demonstration of WHO’s commitment to and capability of supporting the health needs of the Somali people especially in a crisis of this scale.

The implementation of the EWARN system has greatly improved the detection, verification, investigation and reporting of diseases of public health importance in the country in real time, and the sharing of relevant health information with health partners and stakeholders to guide response activities and monitor the trends of these diseases across the country.