Stopping the traffic to offer life-saving care during emergencies

Photo credits: WHO/Andrew Kent

Photo credits: WHO/Andrew Kent

22 November 2021 – Injuries are one of the major public health concerns in Somalia, owing to road traffic accidents and ongoing conflicts. From blast injuries alone, approximately 80 lives are lost every month, and for every death related to an injury, there are 20–50 non-fatal injuries that result in some form of disability, impacting quality of life, productivity and financial security.

There are 2 primary providers for first aid in Mogadishu ─ Aamin Ambulance and the Somali Red Crescent Society ─ but between them they have only 21 functioning ambulances to serve a large population. Approximately, one third of these deaths related to injuries could be avoided if community trauma care, paramedical services and transportation were made available. However, there is currently no effective pre-hospital care system beyond Mogadishu and after emergencies, patients are rushed to hospitals through their own means, often in a private vehicle or carried by relatives.

The lack of an organized pre-hospital transportation system, along with no organized community first aid means that the delay between the point of injury and first contact with the hospital will lead to increased likelihood of death or disability. The situation is further compounded by the lack of a formal organized transport system to move patients from one hospital to another, when they require more complex interventions.

Receiving the right care to avoid injuries and death

Dr Musa Haji, who serves as a first responder to emergencies at the Keysaney Hospital in north Mogadishu, knows the importance of providing early trauma care close to the point of injury.

The driver of the rented car and Ali’s family were not conversant with how to deal with the injuries sustained. If his family had called the local pre-hospital provider, they could have prevented the secondary, serious spinal injury, as Ali would have received professional advice and support.

Investing correctly to reduce high burden and cost of injuries

In low-income countries such as Somalia, families face high burdens and costs of injuries. Yet, this burden can be reduced significantly. Paradoxically, even though Somalia faces recurrent emergencies and natural disasters, it does not have the capacity to offer this crucial support equitably to all of its communities.

“By investing in injury care, we can help communities and countries at large to avoid the exorbitant costs of early death, complications, prolonged recovery, and prevention of disability. The true costs of all these to a family in a fragile, low-income country such as Somalia can be really high,” said Dr Mamunur Malik, WHO Representative to Somalia.

Pre-hospital care key to survival in emergencies

WHO has teamed up with the federal and state ministries of health to build Somalia’s capacity to offer timely and crucial, life-saving prehospital care. This is an integral component of both the emergency care pathway, a journey that begins at the point of injury through to the hospital, and a patient’s referral pathway, which facilitates the transfer of patients with medical conditions from the point of injury or one health care facility to a health facility that can offer the right attention.

“The training and support that WHO and the Government are offering to first responders will serve as scaffolding for emergency health services in Somalia, as we are empowering both health professionals and eventually lay people at the front lines, from the point of an incident or injury to facilities that can care for victims, right back to victims’ reintegration in the society,” added Dr Malik.

As part of this initiative, a team of experts from the WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean and WHO country office conducted a workshop on 2 November 2021 to engage with 15 participants from various ambulance services, mostly based in Mogadishu.

“Our findings have revealed that between 60 and 80% of all trauma deaths in humanitarian emergencies across the Eastern Mediterranean Region, occur before reaching the hospital, frequently referred to as dead on arrival (DOA). Community volunteers and frontline providers lack training and supplies for basic life-saving interventions, such as haemorrhage control and airway management. It follows then, that by focusing on immediate and early trauma management as the first phase of this initiative, a significant number of deaths can be demonstrably avoided,” said Dr Sara Halimah, WHO Regional Trauma Specialist.

During their discussions at the workshop, participants also discussed the current situation and low-cost, high-impact solutions to establishing pre-hospital care.

“People don’t make way for us”

Participants also highlighted some of the challenges they face, including no roads and insecurity, which hinders access to people in need.

“At times, when emergencies occur, families of victims don’t call or use us. They prefer to use private vehicles, as they don’t understand what we do, and why we would help them,” said Dr Abdirahman Ali Dahir, Anaesthetist and Consultant from the Aamin Ambulance services. “In many cases, in traffic, people don’t make way for us, as they do in developed countries. The lack of community awareness is a big challenge for us which slows down our response during emergencies.”

In addition to this challenge, most states do not have ambulances. On the limited occasions when ambulances have qualified staff, they do not have adequate life-saving equipment, such as torniquets that can help reduce severe bleeding, and staff cannot access standard accredited courses or training to help them refresh their knowledge, skills, and reaction time during emergencies.

Given the need for frontline emergency responders to continuously develop their skills, workshops like this will help to develop manuals and a roadmap for future training programme. This in turn will have a positive impact on enhancing emergency and trauma care services in the country.

A forgotten conundrum: regulating the use of antimicrobials in a fragile context

Credits: WHO

Credits: WHO

17 November 2021 – World Antimicrobial Awareness Week, commemorated from 18 to 24 November every year, aims to draw attention to the crucial issue of the proper use of antimicrobials, such as antibiotics, antivirals, antifungals and antiparasitics.

This year, the theme for the campaign is to ‘Spread Awareness, Stop Resistance’. The theme calls on 'One Health' stakeholders, policy-makers, health care providers, and the general public to be antimicrobial resistance (AMR) awareness champions.

Improper use of antimicrobials a root cause of resistance

The lack of a functioning national medicine regulatory authority, coupled with unregulated private pharmaceutical suppliers, personnel and quality of medication, has resulted in the circulation of substandard imported medicines and AMR in Somalia. In addition, the misuse and overuse of antimicrobials are the main drivers in the development of drug-resistant pathogens.

Anecdotal evidence states that health care professionals tend to oversubscribe antibiotics, offering them over the counter, without prescriptions, and often without the right advice. Together, these challenges have encouraged the spread of AMR, whereby microbes, such as bacteria, parasites, viruses and fungi, become resistant to antimicrobials. As a result of the high incidence and prevalence of AMR, it is likely that prescription medicines are becoming less effective at fighting infections, which in turn is increasing the risk of disease spread, severe illness and death.

Joining forces to “spread awareness, stop resistance”

“While antimicrobial resistance is a global issue, in Somalia, we can reduce resistance to antimicrobials only if all stakeholders – policy-makers, health care providers and community members, pharmaceutical suppliers – play their role in spreading awareness about the right use of medication, prevention of resistance, and galvanizing consistent action around this topic,” said Her Excellency Dr Fawziya Abikar Nur, the Federal Minister of Health and Human Services in Somalia.

She added that policy-makers can help to design and implement policies to regulate the importation, sales and quality of medications. Communities can be more responsible with the use of medication, noting when to use antimicrobials, and to complete courses once started, for instance. Health professionals can be careful not to overprescribe medications and to dispense only high-quality medication. Agencies such as the media can support to spread the right messages.

Actions being taken to address antimicrobial resistance

In 2020, Somalia developed a national action plan to combat AMR, with support from the World Health Organization (WHO). The plan, which is yet to be endorsed formally by the Federal Government, outlines 4 pillars that would help control AMR — raising awareness, increasing surveillance of cases of drug resistance to infectious diseases, infection prevention and control (IPC), and the proper use of antimicrobials.

Recognizing the interconnectivity between humans, animals and plants outlined in the ‘One Health’ approach, the national action plan also advocates for the prevention of AMR at the human-animal interface and in food chains, by raising awareness as well as by implementing concrete health actions.

Highlighting ways in which Somalia and its partners can address this situation, Dr Mamunur Rahman Malik, WHO Representative to Somalia said, “Education is a key component in driving action. Even though we have seen many other urgent health issues such as COVID-19 take over the limelight, we must have conversations about the impact of antimicrobial resistance on the health of both humans and animals, and to incorporate this topic at all levels of health education.”

AMR remains a global health and development threat. It requires urgent multisectoral action in order to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). WHO has declared that AMR is one of the top 10 global public health threats facing humanity. The cost of AMR to the economy is significant. In addition to death and disability, prolonged illness results in longer hospital stays, the need for more expensive medicines and financial challenges for those impacted. Without effective antimicrobials, the success of modern medicine in treating infections, including during major surgery and cancer chemotherapy, would be at increased risk.

Somalia will celebrate the week through awareness raising sessions among health care providers and policy-makers in the country, as well as through committing to implement the national action plan for AMR, costing the national action plan, taking concrete actions for understanding the burden of AMR in the country through point prevalence studies, and introducing a sentinel-based surveillance system for regularly monitoring the threat and trend of AMR in the country. Building country capacity for detection and responding to the emerging threat of AMR in the country will be at the heart of these activities.

For additional information, please contact:

Khadar Hussein Mohamud

Head of Coordination and Communication

Federal Ministry of Health and Human Services, Somalia

+252 615 602 637

Fouzia Bano

WHO Chief of Staff ai, Communications Officer

+252 619 235 880

Saving lives and reducing disability from injuries in Somalia: a new approach to trauma care

11 November 2021 – In the last 3 decades, Somalia has faced protracted conflict and emergencies — as a result of which the high burden of injuries has been ubiquitous and often poorly addressed from the public health lens.

The public health burden of injuries and trauma

In December 2020 and January 2021, the Federal Ministry of Health, with technical support from World Health Organization (WHO), conducted a rapid assessment of critical care services in 136 hospitals across 18 regions and focus group discussions with frontline health care workers in Somalia. This was supported by the World Bank under its Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility to improve access to health services in Somalia.

The assessment revealed that trauma imposes a heavy burden on the Somali health system and the community at large. The hospitals had recorded more than 37 000 civilian trauma cases over 12 months. Yet, the survey referred to cases of conflict alone. If it had included road traffic accidents, domestic injuries and burns, or covered small peripheral hospitals and primary health care centres, the number of civilian trauma cases recorded would have been even higher. The Global Burden of Disease Study published in 2019 by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Seattle, shows that the share of the disability burden of injuries increased from 6.23% in 2000 (age-standardized rate: 5617.28 disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost per 100 000 population) to 8.60% (age-standardized rate: 5739.72 DALYs lost per 100 000 population) in 2019. These figures are projected to increase to 6300.88 age-standardized DALYs per 100 000 population and 6.49% of DALYs lost in Somalia in 2030. The substantial increase in conflict and terror as well as the increased burden of road injuries observed between 2000 and 2019 were the main factors driving the upward trend in injury-related deaths and disability in Somalia. The study also showed that deaths caused by injuries were estimated to be 119.10 per 100 000 population in Somalia in 2019, and injuries were responsible for an estimated 7.35% of all deaths reported in the country.

Injuries and trauma pose a double threat to affected communities. In addition to the physical burden caused by injuries, trauma is also known to have a negative effect on the socioeconomic environment in a country. By this measure, it increases poverty levels, as families of the injured need to spend substantive time, money and efforts caring for their loved ones.

The capacity of the existing system

In Somalia, there is a scarcity of health personnel. For example, there are no paediatric trauma specialists and no recognized medical anaesthetists working in the public sector. Half of the hospitals surveyed functioned with only one or 2 general surgeons and only 5 hospitals claimed to have surgeons with a background in orthopaedic surgery.

There is currently no effective pre-hospital system beyond central Mogadishu; and communities in rural and remote areas have little or no access to trauma care. In the wider picture, this includes maternity services and women die needlessly for want of basic prehospital care.

“It is an undeniable paradox that in recent times those most in need of trauma care services are the least able to access those services. As one of the few UN agencies working in this field, WHO has stepped up to provide technical assistance and coordinate the trauma care response in the country,” said Dr Mamunur Rahman Malik, WHO Representative to Somalia. “This support is largely being steered by the Government of Somalia, and we are working closely with hospitals and personnel to make advances in this field.”

Establishing a WHO trauma programme for Somalia

The WHO country office for Somalia, with support from the WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, is setting up a trauma care programme that is built on the vision of a holistic approach to trauma, from the point of injury, when one is injured, through surgery to the physical rehabilitation of the patient, back into the community.

As part of this initiative, the WHO delivered the first Surgical Team Approach to Trauma (STAT) course, using high technology surgical simulation facilities and virtual reality. Overall, 31 health workers were trained, bringing together surgeons and anaesthetists to embed a team-based approach to trauma management. The training took place from 3 to 7 October in Mogadishu and 11 to 15 October 2021 in Berbera. Trainees were exposed to high fidelity scenarios in an operating theatre, all while observing strict COVID-19 protocols and minimizing the spread of infection. They also learnt how to use ultrasound at the point of care and in emergency departments.

As an anaesthetist working at the Baidoa Medical Hospital, Dr Abdirahman Mohamed Hassan shared his reflections:

Trainees were able to watch live how a trauma teams works in other contexts, including the UK“After the training, I realized the value of working together as a team in my hospital. Now, we have started to share all the knowledge we have and experiences we go through, both in person and on group chats, and it feels really good for all of us, as we are learning best practices together every day. I can already see that this has better outcomes for our patients. Before this, there was no groupwork or teamwork – we all worked on our own,” Dr Hassan said.

Trainees were able to watch live how a trauma teams works in other contexts, including the UK“After the training, I realized the value of working together as a team in my hospital. Now, we have started to share all the knowledge we have and experiences we go through, both in person and on group chats, and it feels really good for all of us, as we are learning best practices together every day. I can already see that this has better outcomes for our patients. Before this, there was no groupwork or teamwork – we all worked on our own,” Dr Hassan said.

Two other crucial lessons Dr Hassan learnt is that anaesthesia can be administered on patients even if they aren’t fasting, as previously, he believed he had to wait until the patient had been on an empty stomach for a while, which caused unnecessary delays in fragile situations. Dr Hassan also learnt that anaesthetists play a key and active role in responding to trauma patients, and that their role is not limited to addressing patients before and during the surgeries.

“Last week, a 35-year-old man who was involved in a car crash outside Baidoa was rushed to the hospital. He was bleeding profusely around his pelvic area. I took over the situation as a team lead. I assessed the case, compressed the wound, checked the patient’s airway, offered intubation, and rehydrated him. I worked swiftly with the teams in the emergency ward and operating theatre, and, of course, also checked on the patient before, during and after the surgery,” said Dr Hassan. “I was so confident in my response to him, thanks to this training by WHO.”

Using creative and effective ways to create an impact

Both the Ministry of Health and WHO also arranged for trainees to work in simulated situations in high-quality operating theatres. By way of this initiative, they learnt how to maintain hygiene and wear their protective equipment to reduce the spread of infections.

The trainers also lent the participants modern, virtual headsets for them to use to test their knowledge, by experiencing different virtual reality scenarios. Trainers used these creative and highly effective methods of imparting knowledge in addition to presentations and theory.

Dr Sara Halimah, WHO Regional Trauma Specialist, explained that the trauma programme attempts to provide a stepwise, practical, and realistic approach to the management of victims of trauma.

“Although the acute humanitarian needs of Somalia are at the heart of this initiative, it recognises that a long-term problem necessitates a long-term solution, and that humanitarian and development efforts must be aligned to build a trauma care system that not only responds to today’s humanitarian needs but also developing a system that will serve the future needs of Somalia to reduce the high burden of injuries as a public health problem in the country,” Dr Halimah added.

Through the training, health professionals worked with animal carcasses to learn how to address bullet wounds

Through the training, health professionals worked with animal carcasses to learn how to address bullet wounds

Building on what has been achieved with support from the World Bank‘s funding from Pandemic Emergency Financing Facility in January-March 2021 and capitalizing on this new initiative on “Surgical Team Approach to Trauma (STAT),” the WHO country office will work with the federal and state ministries of health to set up a trauma care system as part of emergency, critical and operative care services in the country, as part of Somalia’s overarching goal of achieving universal health coverage, leaving no one behind.

Somalia receives another shipment of 336 500 doses of Johnson & Johnson vaccines donated by the United States Government through the COVAX Facility

Credit: UNSOM/Mukhtar Nuur

Credit: UNSOM/Mukhtar Nuur

8 November 2021 – As the head of the Shabellow Bay Camp for internally displaced persons in southwest Somalia Ibrahim Mohamed Ali spends a lot of his time trying to convince his community members to get vaccinated against COVID-19.

Ibrahim explains that even though his cousin in Baidoa had advised him to get vaccinated earlier on, he was not totally convinced at first, as no one seemed to know enough about the virus and vaccines — it all seemed so new to everyone.

“After seeing a number of my friends in the camp die all of a sudden due to COVID-19, I realized that the vaccination would help me to fight COVID-19 and could save my life,” said Ibrahim.

He adds, “This was the first time I had ever received a vaccine for my health, and I am so thankful to the Ministry of Health, the World Health Organization (WHO), UNICEF and all donors who have made the effort to support me and other Somalis to keep safe from COVID-19.”

Support from the US Government key to preventing COVID-19 spread

Somalis have been able to receive COVID-19 vaccines with the support of donors such as the Government of the United States of America (USA), through the COVAX Facility. WHO and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) have been supporting the federal and state ministries of health to offer vaccines in all states.

In August 2021, the US Government donated 302 400 doses of Johnson & Johnson vaccines to Somalia. Following this, on 7 November 2021, Somalia received another shipment of an additional 336 500 doses of Johnson & Johnson vaccines. In a country where an estimated 2.6 million people are permanently internally displaced and an estimated 26% of the country’s population are nomadic, this one-dose regimen of COVID-19 vaccines are ideally suitable for Somalia to fully vaccinate as many at-risk populations as possible to end the pandemic.

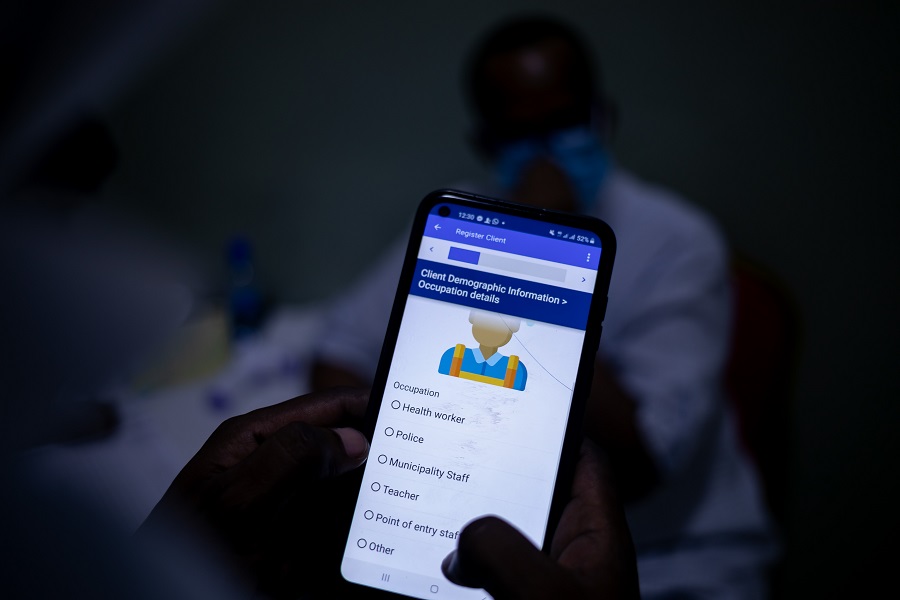

Credit: WHO Somalia/Ismail Taxta

Credit: WHO Somalia/Ismail Taxta

“The one-dose COVID-19 vaccines that Somalia has received are a game-changer for the country’s displaced, nomadic and other vulnerable populations as this is a one-dose regimen unlike other COVID-19 vaccines and owing to the mobility of these groups of people, this one dose can offer immunity and protection to these groups and can rapidly increase the number of people fully vaccinated against COVID-19 in the country,” said Dr Mamunur Rahman Malik, WHO Representative to Somalia.

Already popular within communities, the Johnson & Johnson vaccine needs only one dose to be administered to offer protection against COVID-19. This consignment of vaccines will be used to protect mainly internally displaced persons, nomads and other populations who are difficult to access.

Fewer women than men vaccinated so far

Credit: WHO Somalia/Ismail Taxta

Credit: WHO Somalia/Ismail Taxta

As of 6 November, Somalia had administered 693 683 doses of COVID-19 vaccines, which can be translated as 4.43 doses/100 people administered. So far, 2.37% of the Somali population have been partially vaccinated and 2.06% have been fully vaccinated, with most of the doses having been administered in urban areas. Just over one third (39%) of people vaccinated are women.

The Ministry of Health, with support from WHO and UNICEF, will deploy 496 teams in November 2021 to reach more people with the COVID-19 vaccines received, in an effort to prevent further spread of COVID-19.