While the COVID-19 response dominates community health concerns, every missed opportunity for vaccination puts the fragile gains made against polio in Somalia at risk of being undone

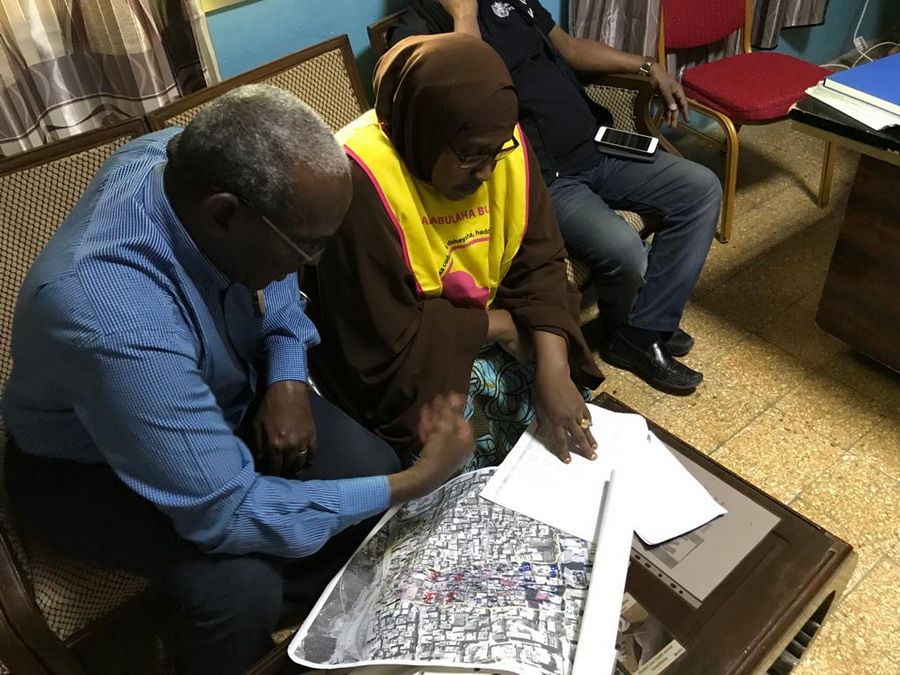

Community surveillance teams for COVID-19 and acute flaccid paralysis speak to households about any individuals with symptoms in their area. The Somali polio team is currently steering the COVID-19 response and fighting ongoing polio outbreaks amid challenging conditions. Photo: WHO/Somalia

Community surveillance teams for COVID-19 and acute flaccid paralysis speak to households about any individuals with symptoms in their area. The Somali polio team is currently steering the COVID-19 response and fighting ongoing polio outbreaks amid challenging conditions. Photo: WHO/Somalia

22 July 2020 – For Somalis, COVID-19 is the most immediate crisis in a seemingly unending cycle of floods, food insecurity, conflict and outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases like measles, cholera and polio. Against this backdrop, WHO’s polio programme is working to steer the COVID-19 response and, more broadly, maintain vaccine immunity levels and improve access to health care. It’s no easy feat.

Dr Mohamed Ali Kamil, the outgoing WHO Polio Team Lead and COVID-19 incident manager for Somalia, is in awe of the commitment shown by health staff. He recently phoned a polio logistician diagnosed with COVID-19 who was experiencing symptoms to insist he stop working remotely from his sickbed. Dr Kamil recalls he said, “No sir, I will continue.”

Since the first COVID-19 case was diagnosed in Somalia on 16 March 2020, the polio programme has fought the pandemic from the ground up. Dr Kamil explains, “No other health programme has comparable expertise to serve the Somali population during the COVID-19 outbreak. During their time in the programme, members of the polio team have responded to many different disease outbreaks. This meant they were well placed and well trained to respond to COVID-19.”

“The polio programme has spent years building staff capacity and systems to implement vaccination campaigns and detect poliovirus in the community. In some ways, the team are the first and last line of defence.”

Dr Mohamed Ali Kamil, the outgoing WHO Polio Team Lead and COVID-19 incident manager for Somalia, speaks to a polio vaccinator before the onset of the pandemic. Photo: WHO/Somalia

Dr Mohamed Ali Kamil, the outgoing WHO Polio Team Lead and COVID-19 incident manager for Somalia, speaks to a polio vaccinator before the onset of the pandemic. Photo: WHO/Somalia

The response includes education, case identification, contact tracing, case management and data support. As of June 2020, polio staff working as part of rapid response teams had reached 2.6 million people with messages about COVID-19 prevention. District Polio Officers within the teams have led the investigation of over 4500 people with suspected COVID-19 across the country. The country has set up 3 COVID-19 testing facilities and the polio structure established for the collection and shipment of stool samples from acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) cases has been used for the transportation of COVID-19 samples.

Throughout, polio personnel have continued their full-time work to end the circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV) outbreaks that have thus far paralyzed 16 children since 2017.

The team are driven by a humanitarian commitment to the Somali population, who have suffered over 30 years of protracted conflict and insecurity. At least 5.2 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance, and secondary and tertiary health care is virtually non-existent outside of a few large cities. Health literacy is low, and populations are highly vulnerable to diseases like polio, measles, cholera and now COVID-19. In November 2019, widespread flooding brought further turmoil and danger to Somali families.

The team’s work is made more difficult by the emotional toll wrought by the pandemic. To date at least 143 health workers have been identified with COVID-19 infection. In April, Ibrahim Elmi Mohamed, a District Polio Officer who spent 19 years striving for a polio-free Somalia, died of a COVID-19-related illness. His death, one of the many of frontline staff around the world due to COVID-19, remind us of the risks they face every time they go to work.

Challenges lie ahead to defeat polio

Dr Kamil is clear that the polio programme will require ongoing funding and the support of authorities, partners and communities in order to maintain polio activities amid the pandemic.

“To sustain the immunity gains we must implement a number of polio vaccination campaigns each year until the routine immunization programme can reach every Somali child with all polio vaccines. Somalia is extremely fragile and at high risk of becoming endemic for poliovirus if we do not maintain and support the polio infrastructure,” he says.

Since the cVDPV outbreaks were first detected in 2017, the programme has streamlined disease surveillance for cases of AFP and other preventable diseases, including by introducing mobile technology to record details of suspected cases. For the first time, environmental disease surveillance was introduced. Over 3 years, frontline health workers have implemented more than 15 polio campaigns, including integrated campaigns with the measles programme.

A volunteer vaccinator gives 2 drops of the polio vaccine to a Somali child in August 2019. Despite efforts, many inaccessible areas remain where the programme cannot deliver vaccines. Photo: WHO/Ilyas Ahmed

A volunteer vaccinator gives 2 drops of the polio vaccine to a Somali child in August 2019. Despite efforts, many inaccessible areas remain where the programme cannot deliver vaccines. Photo: WHO/Ilyas Ahmed

Dr Kamil explains, “We still don’t know where the virus is coming from exactly. There are many inaccessible areas, where we cannot deliver vaccines or respond with immunization campaigns. We suspect that the virus is circulating among vulnerable children and communities living in these areas.”

Dr Kamil feels strongly that the polio programme has a duty to support other health interventions. He says, “COVID-19 shows what the frontline polio staff can achieve and the strength of surveillance and response systems.’’

Despite the challenges, Dr Kamil retains his belief that with ongoing funding and support, the cVDPV outbreaks in Somalia can be brought to a close. He reflects, “COVID-19 is a huge emergency in Somalia. Our staff are working flat out, and we expect to see many more cases, but at the same time we must continue to fight polio. The Somali community and the world deserve to be free of this disease.”

“We must reschedule our March polio vaccination campaign which was delayed because of the COVID 19 outbreak. We must do everything possible to keep health workers safe from COVID-19. It’s a hard situation, but we must not stop until we overcome both viruses.”