December polio vaccination begins

KABUL, 13 December 2021 - The fourth round of a national polio immunization campaign begins this week (13–16 December 2021), and will be synchronized with Pakistan to improve cross-border polio eradication efforts. The campaign targets 9.9 million children aged 0–59 months across the country and is scheduled to start later this month in some parts of the country, including in the south and east, and in the provinces of Paktia and Ghazni in the south-east, Ghor in the west, and Balkh in the north.

This is the second campaign this year to reach children in areas previously inaccessible to the polio programme. A campaign in November 2021 delivered polio vaccinations to 8.5 million children under the age of five, including 2.4 million children who were vaccinated for the first time in over three years.

“We are intensifying efforts to reach the maximum number of children across the country, but we need sustained access to rapidly build immunity against polio, especially in areas we have not been able to reach in the last few years,” said Dr Dapeng Luo, WHO Representative in Afghanistan. “The November campaign was a massive leap forward and the upcoming campaign will further strengthen the progress we are making. Six more campaigns are planned for 2022 and we must ensure they are implemented in a timely fashion and reach all children,” he said.

To date, 2021 has been the year with the lowest polio transmission in both Afghanistan and Pakistan. This provides a great opportunity to interrupt transmission of wild poliovirus and achieve eradication.

Four wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV1) cases have been reported in the country so far this year. The first WPV1 case of 2021 was reported in January 2021 from Ghazni province in the south-east of the country, while the other three cases were reported in October and November from Kunduz province in the north-east.

The polio programme has put urgent measures in place to boost immunity in Kunduz and other high-risk areas to stop the polio outbreak and protect children from this crippling but preventable disease.

“Immunization is one of the most cost-effective public health interventions, saving children’s lives and contributing to a better future for Afghan children,” said Alice Akunga, UNICEF Representative a.i. “We must intensify our efforts to reach all children, especially those in greatest need, in order to bring polio disease under control,” she said.

Frontline workers are the pillar of successful vaccination drives. The polio programme is calling on all leaders, stakeholders and communities to ensure the safety of all frontline workers for the successful implementation of the campaign.

Islamic Republic of Iran

Epidemic estimates

|

|

2020 |

|

Adult (15 to 49) HIV prevalence |

<0.1 [<0.1–0.2] |

|

Adults and children living with HIV |

54 000 [39 000–130 000] |

|

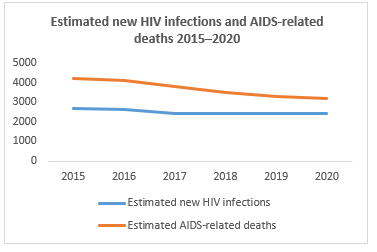

New HIV infections |

2400 [1000–11 000] |

|

AIDS-related deaths |

3200 [2000–7100] |

|

Percentage change in new HIV infections since 2010 |

-51% |

|

Percentage change in AIDS-related deaths since 2010 |

-12% |

Epidemic transition

|

Percentage change in new HIV infections since 2010 |

-51% |

|

Percentage change in AIDS-related deaths since 2010 |

-12% |

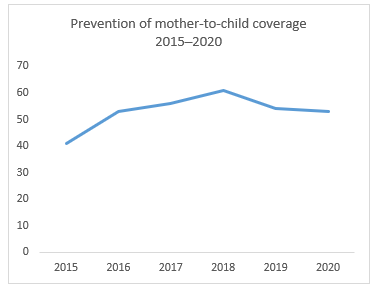

Elimination of mother-to-child transmission

Data on key populations

|

|

Sex workers |

Gay men and other men who have sex with men |

People who inject drugs |

|

Estimated size of population |

138 000 |

– |

90 000 |

|

HIV prevalence |

1.6 |

– |

3.1 |

|

Know their HIV status |

67.1 |

– |

|

|

Antiretroviral therapy coverage |

– |

– |

16.7 |

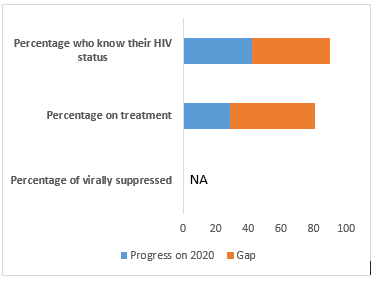

HIV cascade of care 2020

Somalia rolls out FETP-Frontline training programme to build disease detectives/baare and prevent spread of diseases

Having a public health workforce that is able to rapidly detect and respond to disease outbreaks is key for any health system, as recently shown on a worldwide scale with the current COVID-19 pandemic. The importance of this empowered and well-equipped resource is further emphasized by the International Health Regulations (2005), a legal instrument that encourages countries to prevent, detect and respond appropriately to disease outbreaks.

Taking measures to empower health workforce

To address Somalia’s limited capacity in this field, largely a result of decades of political instability, civil unrest, climatic shocks, and man-made and health emergencies, the National Institute of Health (NIH) of the Federal Ministry of Health and Human Services organized the Frontline Field Epidemiology Training Programme (FETP-Frontline), with support from the World Health Organization (WHO), the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US CDC) and the Africa Field Epidemiology Network (AFENET).

The FETP-Frontline programme is a three-month on-the-job training course that addresses the critical skills needed to conduct surveillance and response activities effectively at the local level, focusing on improving disease detection, reporting and response. It is based on the premise that improving the epidemiological skills of staff from the Ministry of Health improves their ability to prevent, detect and respond to public health priority issues, which in turn would improve public health security in a country. It aims to improve field epidemiology knowledge, skills and competencies of trainees, and blends mentorship with classroom training and practical experiences to develop the public health workforce of a country. The trainees spend up to 12 days in three workshops and spend the remaining 8–10 weeks back at their jobs where they conduct field projects to practice, implement and reinforce what they have learned.

The FETP-Frontline programme is part of a three-tiered training model which is implemented in many countries based on the recognition that strengthening the capacity of the public health workforce, especially in fragile, vulnerable and conflict-affected countries, is critical at all levels of health system from the local to the regional and national levels. All three tiers use the same approach of condensed classroom instruction (< 25%) followed by field placements (> 75%) to gain experience and competence in field epidemiology. The other two tiers of the training model are called FETP-Intermediate (a nine-month programme for staff based at regional or national level) and FETP-Advanced (a two-year full time programme for staff at national level).

Rolling out the first phase of the FETP training

The NIH kickstarted the 12-week long FETP-Frontline training programme with a first workshop, conducted from 29 August to 2 September 2021 for 26 participants, followed by the practical field experience, and a second training workshop that ran from 6 to 12 October 2021.

Dignitaries attending the launch of the FETP training on 29 August included: Dr Abdullahi Hashi Ali, Director-General of Health Services, who was representing HE Fawziya Abikar Nur, Minister of Health and Human Services for Somalia; Dr Mamunur Rahman Malik, WHO Representative to Somalia; representatives from the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) Mission; and Dr Abdirahman Abdifatah, Director of the NIH for Somalia. Others who attended included the technical teams of the FETP from AFENET, as well as directors of health and social services from across Somalia’s states.

During the first of three tiers of training, the initial phase focused on training health workers at the frontlines on public health surveillance.

Streamlining reporting through field experiences

Adan Mohamed Ali, who serves the National Malaria Control Programme run by the Federal Ministry of Health and Human Services of Somalia, was one of the first 26 participants to attend the preliminary FETP training.

He explains that during the initial parts of the five-day classroom learning, he learnt a lot about disease surveillance, monitoring and evaluation, descriptive epidemiology and case investigation. As part of the on-the-job training, which comprises 75% of each training course, Adan visited health facilities in the district of Kahda, Banadir region. The second part of the training focused on presenting results, outbreak investigation and response, laboratory collection and transport, problem analysis and communication.

“While conducting the audit, I was supposed to visit six health facilities. However, only two were still functioning and one was reporting to the EWARN. I tried to convince the closed facilities to reopen to help in reporting and the search for diseases, which would help the Government to prevent spread of diseases in communities,” explains Aden. “Through the field exercise, I learnt how to identify the gaps and challenges of health facilities. I studied records for weeks 1–36 for this year, log books, tally sheets, charts and graphs and interviewed health facility staff to analyse the timeliness of reporting and discuss problems the staff face in reporting.”

He added that efforts like this were important as they would help the country’s health system to streamline reporting and surveillance for diseases.

Upon completion of the three-month FETP-Frontline training programme, Adan and other successful trainees will move on to the intermediate and advanced level courses, while at the same time becoming trainers for the next cohort.

Impact of the FETP

The evaluation of the first series of trainings shows an encouraging rise in trainees’ knowledge, which they are now applying in their daily work. The programme will help increase the capacity of Somalia’s health workforce in surveillance and outbreak response at all levels of service delivery. Indeed, demonstrable improvements in surveillance and response indicators, including the timeliness and completeness of reports, have been shown in other countries where the Frontline-FETP programme has been implemented extensively. Moreover, the training will develop the capacity of trainees and health facilities to detect and respond to disease outbreaks in a timely manner and minimize the spread of diseases to contain them. Trainees will also gain skills to communicate risk to the public and design messages that will support policy- and decision-makers to implement effective public health responses.

“The WHO country office for Somalia is fully committed to continue working alongside the NIH, CDC and AFENET to roll out the next steps of the FETP programme in Somalia, which will bring the country closer to bridging the current gap in the number of epidemiologists per 100 000 population in Somalia and build a strong cadre of disease detectives in line with the requirements of the International Health Regulations (2005),” said Dr Mamunur Rahman Malik, WHO Representative to Somalia.

“The Frontline-FETP is one of the outcomes of the strong collaboration between the Federal Ministry of Health and our health development partners in addressing the most critical challenges of our health system, which is human resources for health,” said Dr Abdifatah Ahmed, NIH Director.

“I’m a photographer, so my work depends on my sight.”

Tamer is a 39-year-old photojournalist from Rafah in the south of the Gaza Strip, working for the Associated Press (AP).

His sight has been deteriorating since he was diagnosed with a congenital eye condition in 2017. Tamer has required extensive treatments and investigations, not all available in the Gaza Strip. He received initial treatment in Gaza and Egypt, including corneal transplant and cataract operations. Due to the complexity of interventions needed, in February and September 2019 Tamer attempted twice to reach the eye clinic at Hadassah Ein Karim Hospital in Jerusalem but both times he was denied a permit by Israel to reach the hospital.

On the same day that Tamer’s second permit application was denied, he experienced a sudden worsening of his vision while traveling from Gaza City to his home in Khan Younis, in the south of the Gaza Strip. He was diagnosed with detachment of the retina at the back of his eye and needed urgent specialist intervention. The next month, October 2019, Tamer was approved a permit by Israel and Jordan for travel by direct shuttle to Jordan, for treatment in Amman. He traveled, but without any companion to accompany him.

“I needed somebody to guide me because my limited vision. People helped me along the way and in Jordan I asked strangers to help me until I reached the hospital. There the AP [Associated Press] manager in Jordan arrived and he helped me a lot during my stay.”

During his time in Jordan, Tamer saw his mother for the first time in nearly 20 years. She is Palestinian and lives in the town of Al-Lydd (Lod), to the west of Jerusalem. Because she has Israeli citizenship, she has not been able to visit her family in Gaza. Tamer had last seen his mother in Akka (Akko/Acre) in 2000.

Table 1: History of Tamer’s applications for an Israeli medical permit and outcomes

|

Date of application |

Hospital |

Response |

|

21/02/2019 |

Hadassah Ein Karim |

Denied |

|

09/09/2019 |

Hadassah Ein Karim |

Denied |

|

07/10/2019 |

Jordan by Shuttle |

Approved |

|

04/01/2021 |

Hadassah Ein Karim |

Approved |

|

08/02/2021 |

Hadassah Ein Karim |

Approved |

|

14/02/2021 |

Hadassah Ein Karim |

Approved |

|

01/03/2021 |

Hadassah Ein Karim |

Approved |

|

22/03/2021 |

Hadassah Ein Karim |

Approved |

|

18/04/2021 |

Hadassah Ein Karim |

Approved |

|

26/04/2021 |

Hadassah Ein Karim |

Delayed |

|

24/05/2021 |

Hadassah Ein Karim |

Delayed |

|

13/06/2021 |

Hadassah Ein Karim |

Delayed |

|

27/06/2021 |

Hadassah Ein Karim |

Delayed |

|

01/08/2021 |

Hadassah Ein Karim |

Delayed |

In Jordan, Tamer had laser treatment to his right eye and surgery in his left. From January 2020, he received his first permit approval to reach Hadassah Ein Karim Hospital in Jerusalem, and he traveled to the hospital six times between 4 January and 18 April.

“At Hadassah, they told me I would need surgery for my right eye as well, but it would only be possible after my left eye improved… I had smooth access to Hadassah up until [April]... After that, I lost five appointments. My last application for 1 August was not approved in time for my appointment.”

Tamer talked about how his illness and the uncertainty of accessing treatment has affected his health and his family life during these past years.

“I want to go back to what I had before, even half the vision I had before. I’ve gained weight and it hurts to stay at home and not be able to move like I used to. I’ll apply as many as needed to get a permit to reach treatment but waiting is unbearable. The AP [Associated Press] is trying and won’t stop until we get good news. I need the treatment; I can’t stay at home like this. I’ve had to bear this for three years.

My children are young, and my wife has supported me through all this. The kids see their father stay home rather than the active father they knew before – who was working, who took them out, who took them down to the beach. I’m not able to do any of those things with them now.”

As a photojournalist, Tamer worries about his work and his future.