Research article

A.M. Aboul-Fotouh,1 N.A. Ismail,1 H.S. Ez Elarab 1 and G.O. Wassif 1

تقييم ثقافة سلامة المريض لدى مقدمي الرعاية الصحية في مستشفى تعليمي في القاهرة، مصر

عائشة محمد أبو الفتوح، نانيس أحمد إسماعيل، حنان سعيد عز العرب، غادة أسامة واصف

الخلاصـة: أوضحت دراسة سابقة أجريت في القاهرة، مصر، مدى الحاجة إلى تحسين ثقافة سلامة المريض لدى مقدمي الرعاية الصحية في مستشفيات جامعة عين شمس. وتقدم هذه الدراسة المستعرضة التوصيفية تقييماً لمدى استيعاب ثقافة سلامة المريض داخل المؤسسة، كما أنها تحدِّد العوامل التي ساهمت في تشكيل ثقافة سلامة المريض. وقد تناولت الدراسة عينة ممثِّلة تتألف من 510 طبيباً وممرضة وصيدلانياً وتقنياً ومختبرياً من مختلف الأقسام، وقد أجابوا على النسخة العربية من المسح الذي أعدَّته وكالة البحوث حول الرعاية الصحية والجودة في المستشفيات، لتحديد معارفهم حول ثقافة سلامة المريض. وقد كان الـحَرَز الوسطي الأعلى الإيجابي من بين اثني عشر بُعداً يتعلق من نصيب التعلّم المؤسسي المستهدف للتحسين المستمر (%78.2)، ويتلوه العمل في فريق (%58.1). أما الـحَرَز الوسطي الأدنى وهو الخاص بالبُعد المتعلق بالاستجابة غير التأديبيَّة للخطأ فكان %19.5. وقد توصَّلت الباحثات إلى أن ثقافة سلامة المريض لايزال فيها العديد من المجالات للتحسين وأنها تحتاج تقييماً مستمراً ومراقبة متواصلة لضمان الحصول على بيئة آمنة لكلٍ من المرضى ومقدمي الرعاية الصحية.

ABSTRACT A previous study in Cairo, Egypt highlighted the need to improve the patient safety culture among health-care providers at Ain Shams University hospitals. This descriptive cross-sectional study assessed health-care providers’ perceptions of patient safety culture within the organization and determined factors that played a role in patient safety culture. A representative sample of 510 physicians, nurses, pharmacists, technicians and labourers in different departments answered an Arabic version of the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality hospital survey for patient safety culture. The highest mean composite positive score among the 12 dimensions was for the organizational learning for continuous improvement (78.2%), followed by teamwork (58.1%). The lowest mean score was for the dimension of non-punitive response to error (19.5%). Patient safety culture still has many areas for improvement that need continuous evaluation and monitoring to attain a safe environment both for patients and health-care providers.

Évaluation de la culture de la sécurité des patients chez des employés d'un hôpital universitaire au Caire (Égypte)

résumé Une étude antérieure menée au Caire (Égypte) a souligné la nécessité d'améliorer la culture de la sécurité des patients chez les employés du Centre hospitalier universitaire Ain Shams. La présente étude descriptive et transversale a évalué les perceptions des employés en termes de culture de la sécurité des patients au sein de l'établissement et a déterminé les facteurs influant en la matière. Un échantillon représentatif de 510 médecins, personnels infirmiers, pharmaciens, techniciens et autres agents dans différents services a répondu à l'enquête hospitalière sur la culture de la sécurité des patients de l'Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality [Agence pour la recherche et la qualité des soins de santé] dans sa version arabe. Le score positif composite moyen le plus élevé parmi les 12 dimensions était l'apprentissage organisationnel en vue d'une amélioration continue (78,2 %), suivi par le travail d'équipe (58,1 %). Le score moyen le plus faible concernait la dimension d'une réponse non punitive à l'erreur (19,5 %). Les améliorations à apporter à la culture de la sécurité des patients restent nombreuses. Pour créer un environnement sûr à la fois pour les patients et pour les prestataires de soins de santé et les autres employés, une évaluation et un suivi continus sont requis.

1Department of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt (Correspondence to H.S. Ez Elarab:

Received: 20/04/10; accepted: 25/07/10

EMHJ, 2012, 18(4): 372-377

Introduction

Patient safety is defined as avoidance and prevention of patient injuries or adverse events resulting from the processes of health care delivery [1]. The safety culture of an organization acts as a guide as to how employees will behave in the workplace. Of course their behaviour will be influenced or determined by what behaviours are rewarded and acceptable within the workplace [2]. Safety culture is defined as the collective product of individual and group values, attitudes and patterns of behaviours in safety performance. The characteristics of a strong and proactive safety culture include the commitment of the leadership to discuss and learn from errors, to document and improve patient safety, to encourage and practise teamwork, to spot potential hazards, to use systems for reporting and analysing adverse events and to celebrate workers as heroes improving safety rather than as villains committing errors. Organizations with a positive safety culture are characterized by communications founded on mutual trust, by shared perceptions of the importance of safety and by confidence in the efficacy of preventive measures [3]. Despite the emphasis on patient safety in health care, few organizations have evaluated the extent to which their staff culture supports patient safety [4].

In 2005 in Egypt a study of patient safety was performed and disseminated for policy change as a part of regional study within countries in the Eastern Mediterranean region (EMR). It determined the nature and rate of adverse events in 3 hospitals in Cairo through a review of the medical records. Although the recorded adverse event rate was low (ranging from 1% to 11%, average 6%), 34% of such adverse events were associated with the patient’s death and 18% with permanent disability. Factors associated with a low rate of adverse events were inadequate reporting and inadequate documentation within the hospital medical records. The study highlighted the need to improve the patient safety culture among health care providers at Ain Shams University hospitals and to develop their willingness to act to reduce patient harm [5].

The aims of this study were to assess their perceptions of patient safety culture dimensions among health-care providers in different departments at Ain Shams University hospitals and to determine which factors played a role in better patient safety culture.

Methods

Study setting and sample

This descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted at Ain Shams University hospitals, in different medical and surgical units, intensive care units (ICUs) and paramedical departments.

The total number of health-care providers working at Ain Shams University hospitals was 9164. A representative sample of health-care providers from different job categories in the selected units —physicians, nurses, pharmacists, technicians, and labourers—were enrolled in our study after giving their approval for participation. The sample size was estimated to be 369 health-care providers using a sample size calculator [6] given that α equals 0.05, power of 80%, confidence level of 95%. The sample size was doubled to 738 to allow for a response rate of 50%.

Sample recruitment was carried out by visiting all medical and surgical departments as well as ICUs, pharmacies and laboratories (in the obstetrics/gynaecology, internal medicine and surgery hospitals) 4 times per week.

Data collection

Data collection was from November 2008 to May 2009. The self-administered questionnaire was distributed to professional and literate members of staff and then collected at the next visit. For staff who were illiterate or failed to understand the questions easily (housekeepers, labourers, porters), the questionnaire was delivered as an interview by the researcher.

The questionnaire was adapted from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s hospital survey on patient safety culture [7], pilot tested, revised and then released in November 2004. It was designed to assess hospital staff opinions about patient safety issues, medical error and event reporting and measures 12 dimensions of patient safety culture. The dimensions measured are: communication openness, feedback and communication about error, adverse event reporting and recording, hand-offs and transitions, management support for patient safety, non-punitive response to error, organizational learning/continuous improvement, overall perceptions of patient safety, staffing, supervisor/manager expectations and actions promoting safety and teamwork across and within units. Most of the questionnaire items require respondents to answer on a 5-point Lickert scale in terms of agreement (strongly agree, agree, neither, disagree, strongly disagree) or frequency (always, most of the time, sometimes, rarely, never).

The questionnaire was translated into Arabic and modifications were made by the addition of some topics such as: personal information, punitive response to error in the hospital, type of punishment, adverse event reporting and recording systems at Ain Shams University hospitals. A pilot study was carried out on approximately 10% of the sample size taken from the same study population but not from the study sample

Ethical approval to carry out the study was obtained from the administrative and ethical committee board. Informed consent was obtained from participants before they were enrolled in the study.

Data analysis

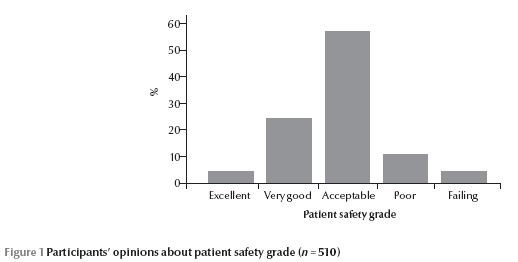

Each questionnaire was examined for accuracy and completeness and incomplete questionnaires were excluded from the data set. A composite score was calculated which was the average percentage of positive responses to the survey items in each dimension of safety culture. This provided a summary how positively people answered the items in each safety culture dimension. If the composite score for all items in the same patient safety dimension was more than 75%, this patient safety dimension was considered as an “area of strength” and if it was less than 50%, this patient safety dimension was considered as “an area with potential for improvement” [8]. Patient safety grade was estimated from respondents’ overall grading of their work area or unit as: excellent, very good, acceptable, poor or failing.

The collected data were analysed using SPSS for Windows, version 16. Qualitative data were presented using frequencies and percentage comparisons were done using chi-squared test. For quantitative data: comparisons between groups’ composite scores was done by 1-way ANOVA if more than 2 groups and t-test for independent samples if 2 groups. P-values < 0.05 were treated as significant.

Results

Background characteristics

The final study sample was 510 health-care providers, i.e. a response rate of 69.1%. The majority (43.5%) were aged 25–35 years, females were 76.1% and more than half were junior staff, i.e. working for less than 5 years. Half of them (50.0%) were physicians and 86.1% were dealing directly with patients in clinical services (Table 1).

Patient safety culture scores

The summarized composite scores on the 12 dimensions of patient safety culture (Table 2) show that the highest mean composite positive score (78.2%) was for organizational learning for continuous improvement. The individual item with the highest mean percentage positive response (85.0%) was “Mistakes have led to positive changes here”. The next highest scoring dimension was teamwork within hospital units (58.1%), in which the item with the highest average percentage positive response (73.8%) was “People support one another in the unit”. All the other dimensions had composite scores below 50%: staffing work conditions (49.3%), supervisor/manager expectations and actions promoting safety (46.4%), feedback and communication about error (39.7%), overall perception of safety (33.9%), adverse event reporting and recording (33.4%), teamwork across hospital units (38%), communication openness (34.6%), hospital management support for patient safety (27.2%) and hospital hand-offs and transitions (24.6%). The lowest mean composite positive score was for the dimension of non-punitive response to error (19.5%).

Table 3 shows that participants aged 35+ years had higher mean patient safety culture scores in all dimensions than those aged 18–34 years. Also those who had worked longer in their specialty had higher scores for all dimensions than those working for fewer years and there was a statistically significant difference between composite scores in different age groups with regard to feedback and communication about error. There was no significant difference between male and female participants in any of the patient safety dimensions.

The composite scores for paramedical personnel who had indirect contact with patients was higher than for physicians and nurses who had direct contact with patients in most of the patient safety culture dimensions(Table 3).

There was a highly statistically significant difference between the composite scores of physicians, nurses and paramedical personnel with regard to feedback and communication about error and between physicians and paramedical personnel on the item about hospital management support for patient safety (Table 3).

There was no significant difference between participants’ scores by working hours, i.e. those working < 40 hours weekly versus those working 40+ hours, in all patient safety dimensions (Table 3).

Participants’ perception of patient safety grade showed that the same proportion of participants perceived patient safety grade as excellent as those who perceived patient safety grade as failing (3.9%), while the greatest number of participants (57.3%) perceived patient safety grade as acceptable (Figure 1).

Discussion

Patient safety is a critical component of health care quality. As health care facilities continually strive to improve there is a growing recognition of the importance of establishing a culture of safety within the organization [2].

In the present study we attempted to assess the current patient safety culture among health-care providers at Ain Shams University hospitals using a hospital survey for patient safety culture, in which experts delineated a number of safety culture dimensions that a hospital can measure using a culture assessment tool developed for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. There were some limitations to the study which limit it generalization within Egypt as it was a single-centre study and the hospital had some special characteristics, being a university hospital with a particular workload and unique rules for working staff.

The study sample were mainly from the younger age groups and this could be explained by the fact that house officers, resident physicians and junior nurses are more commonly available in the hospital during all the day and night shifts so they were the groups most likely to be available to answer the questionnaire. There were no significant differences between the sexes in any of the patient safety dimensions, presumably as both male and female staff are exposed to the same work environment and regulations.

This survey revealed that the main area of strength regarding patient safety culture in Ain Shams University hospitals was organizational learning which gained the highest average composite positive score of 78.2%. That means that there is a learning culture only when mistakes are disclosed. By definition a learning organization is one that is skilled at creating, acquiring and transferring knowledge and at modifying its behaviour to reflect new knowledge and insights [9].

As regards teamwork within units in our hospitals, the patient safety culture composite score for teamwork was only 58.1%. On the other hand, teamwork within units was an area of strength for most hospitals in the World Health Organization’s 2008 comparative database report in EMR [5]. This is a very important issue as dealing with patients in hospital is usually integrated across different hospital units [8].

All the other dimensions of patients safety culture had mean composite scores < 50% and the lowest was for non-punitive response to error (19.5%). Adverse event reporting and recording was 33.4%. In the 2008 comparative database report the areas identified with potential for improvement for most hospitals were non-punitive response to error and adverse events reporting and recording [8]. Disclosure is very important as a method for risk reduction in organizations, starting with risk reporting, and this is being addressed at our hospitals with the implementation of a quality improvement policy within different departments.

References

- Hospital survey on patient safety culture. The Patient Safety Group [website] (http://www.patientsafetygroup.org/survey/index.cfm?sample=1, accessed 18 January 2012).

- Glendon AI, Clarke SG, McKenna EF. Human safety and risk management. Florida, CRC Press, 2006.

- AHRQ. 2004). Hospital survey on patient safety culture user guide. Rockville, Maryland, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2004.

- Pronovost PJ et al. Evaluation of the culture safety: survey of clinicians and managers in an academic medical center. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 2003, 14(4):231–233.

- Report on the workshop on discussion of the results of the patient safety and their dissemination for policy change, Alexandria, Egypt, 28–31 January 2008. Cairo, World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 2008.

- Sample size calculator. Raosoft [website] (www.Raosoft.com/samplesize.html, accessed 18 January 2012).

- 2008 National healthcare quality and disparities reports. Rockville, Maryland, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2008.

- Customized Excel data tool, version 2007. Premier [website] (https://www.premierinc.com/safety/topics/culture/data-tool.jsp, accessed 29 Febraury 2012).

- Garvin DA. Building a learning organization. Harvard Business Review, 1993, 71(4):78–91.