Review

M. Simbar 1

إنجازات برامج تنظيم الأسرة الإيرانية 1956 - 2006

معصومة سيمبار

الخلاصـة: بدأ العمل في برامج تنظيم الأسرة في جمهورية إيران الإسلامية عام 1966 ولاقى نجاحاً محدوداً. وبعد إحصاء السكان عام 1986 اعتبر تنظيم الأسرة أحد الأولويات، وتلقى الدعم من قِبَل القيادات في البلد. وقد أدت الاستراتيجيات الملائمة التي ترتكز على مبادئ تعزيز الصحة إلى زيادة معدلات انتشار استعمال موانع الحمل بين المتزوجات من %49 في عام 1989 إلى %73.8 في عام 2006. وتستعرض هذه الدراسة برامج تنظيم الأسرة في جمهورية إيران الإسلامية وإنجازاتها خلال العقود الأربعة المنصرمة، وتناقش مبادئ تعزيز الصحة ونظريات تغيير السلوك التي قد تفسر هذه الإنجازات: وقد اشتملت الاستراتيجيات الناجحة على: إيجاد البيئة الداعمة، وإعادة توجيه خدمات تنظيم الأسرة، وتوسيع نطاق التغطية بخدمات تنظيم الأسرة، وتدريب العاملين المهرة، والتزويد بموانع الحمل المجانية وخدمات قطع الأسْهَرَيْن وقطع البوقَيْن المجانية، وإفساح المجال لإسهام المتطوعين والمنظمات غير الحكومية وتعزيز مشاركة الذكور.

ABSTRACT Family planning programmes initiated in the Islamic Republic of Iran from 1966 met with limited success. Following the 1986 census family planning was considered a priority and was supported by the country’s leaders. Appropriate strategies based on the principles of health promotion led to an increase in the contraceptive prevalence rate among married women from 49.0% in 1989 to 73.8% in 2006. This paper reviews the family planning programmes in the Islamic Republic of Iran and their achievements during the last 4 decades and discusses the principles of health promotion and theories of behaviour change which may explain these achievements. Successful strategies included: creation of a supportive environment, reorientation of family planning services, expanding of coverage of family planning services, training skilled personnel, providing free contraceptives as well as vasectomy and tubectomy services, involvement of volunteers and nongovernmental organizations and promotion of male participation.

Réalisations des programmes de planification familiale en Iran de 1956 à 2006

résumé Les programmes de planification familiale instaurés en République islamique d'Iran en 1966 ont rencontré un succès limité. Après le recensement de 1986, la planification familiale est devenue une priorité et a bénéficié de l'appui des dirigeants du pays. Des stratégies appropriées reposant sur les principes de promotion de la santé ont contribué à augmenter la prévalence de la contraception chez les femmes mariées de 49,0 % en 1989 à 73,8 % en 2006. Le présent article examine les programmes de planification familiale en République islamique d'Iran et leurs réalisations au cours des quarante dernières années. Les principes de promotion de la santé et les théories du changement des comportements pouvant expliquer ces résultats sont aussi débattus. Les stratégies efficaces comprennent notamment : la création d'un environnement favorable, la réorientation des services de planification familiale et l'extension de leur couverture, la formation de personnel qualifié, l'offre gratuite de contraceptifs, de prestations de vasectomie et de résection des trompes, la participation de volontaires ainsi que d'organisations non gouvernementales et la promotion de la participation masculine.

1Department of Reproductive Health, Shahid Beheshti Medical Science University, Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran (Correspondence to M. Simbar:

Received: 20/04/10; accepted: 07/07/10

EMHJ, 2012, 18(3): 279-286

Introduction

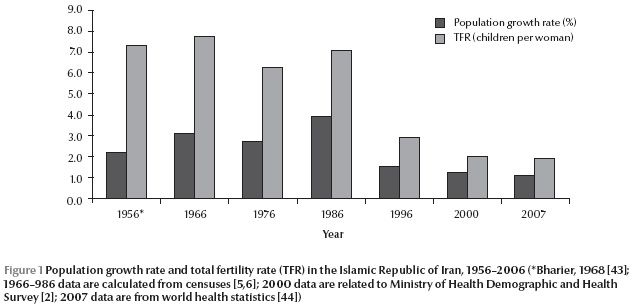

The Iranian government’s success in family planning—which has led to the dramatic decline in the national fertility rate from an average of more than 6 births per woman in the early 1980s to just over 2 births per woman in 2007—has been called the country’s “other revolution” [1]. According to preliminary results of the Iranian Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) for the year 2000, 73.3% of currently married Iranian women aged > 15 years were using a method of contraceptive and the contraceptive prevalence rates (CPR) in urban and rural areas were 77.4% and 67.2%, respectively [2]. These impressively high CPRs put the Islamic Republic of Iran in the upper ranks worldwide for contraceptive use. The average CPRs for the world, more developed regions and less developed regions in 2003 were estimated to be 60.9%, 68.5% and 59.4% respectively [3]. Mirroring this, the Iranian population growth rate decreased from 3.9% in 1986 to 1.5% in 1996 and finally 1.1% in 2005 [4]. The total fertility rate (TFR) also decreased from 7.1 children per woman in 1986 to 2.9 in 1996 [5] and to 2.0 in 2000 [2] and finally 1.9 in 2005 [6]. Around 85% of the changes are due to marital fertility, which suggests that most of the fertility of Iranian women has been controlled within marriage. Around 15% of the change are attributable to changes in nuptiality patterns , specifically an increase in age at marriage and thus a reduction in the proportion of women married at early ages [7].

The achievements of the Iranian family planning programmes (FPPs) have been reviewed by several sociologists and demographers [7–12] but have never been reviewed by health professionals or from a health promotion perspective. This paper aims to review the FPPs and their achievements during the last 4 decades and to discuss the principles of health promotion and theories of behaviour change which may explain these achievements.

Sources

The following of data were used for this review article:

the DHS 2000 carried out jointly by the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MOHME) and the Statistical Centre of Iran (SCI) in the year 2000;

national population censuses conducted by the SCI in 1976, 1986, 1996 and 2005;

annual knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) surveys carried out by the Ministry of Health and Medical Education (MOHME) between 1989–97;

the Iran Fertility Survey conducted by SCI in 1976–77;

indexed research articles in MEDLINE® (http://pubmed.gov/) and Iran’s Scientific Information Database (http://www.sid.ir/Fa/index.asp);

papers by selected Iranian scientists known to the authors who work on Iranian population transition and the Iranian FPP;

other international organizations such as United Nations Population Fund and World Health Organization.

While the data sources for this paper were mostly published in English, many local Farsi language data sources were also included.

History of the Iranian FPPs

FPP before the revolution (1966–76)

The country’s first modern census in 1956 recorded a population of 18.9 million. Although it was indicative of a sudden rise in the population growth rate, Iran was among the countries that voted against the issue of government intervention in fertility control put forward by the United Nations General Assembly in 1962. However, the government’s attitude changed after the release of 1966 census results showing that the Iranian population had reached 26 million. Subsequently the imperial government of Iran adopted a population control policy and established a national FPP in 1967 [8,9]. The Council of Family Planning was established in the Ministry of Health in 1967 and the official FPP was launched with the appointment of an undersecretary in the Ministry [10].

The FPP had 3 stages. During the early 1960s the first stage was mainly focused on enabling family planning choice and decision-making and making contraceptives available through the commercial sector. In the second stage in the later part of the 1960s and early 1970s the main concern of the active FPP was family welfare and the distribution of contraceptives through public clinics. As concern over the adverse effects of population growth on national economic growth heightened in the mid-1970s the third, more active, stage of the programme involved a huge mass media campaign to promote family planning [11]. The FPP became involved in the promotion of certain legislation aimed at improving the status of women, such as raising the age of marriage [12]. According to official statistics, the annual expenditure of the Iranian government on the FPP by 1975 was the second largest amount allocated to family planning among 16 nations [13]. Despite all the resources allocated to the programme and aggressive publicity and social marketing activities undertaken in the 1970s, the fertility survey in 1977, which was the last source of information on the performance of the FPP, showed a 37% contraceptive prevalence rate, including traditional methods, which was much lower for rural (20%) than urban (54%) couples [14,15].

FPP after the revolution (1976–2007)

During the decade 1976–86, the size of the Iranian population increased from 33.7 million to 49.4 million, implying an average annual population growth rate of 3.9% during these years [16] and the TFR increased from 6.3 children per woman in 1976 to 7.1 in 1986 [5].

This high rate of population growth was partly due to 1.8 million Afghan refugees entering the country and an accelerated decline in infant mortality during the 1980s, but the reality was that after the sudden invasion of the Islamic Republic of Iran by Iraq in September 1980 and the start of the 8-year Iran–Iraq war, population and the FPP moved down the list of priorities. But it did not mean the discontinuation of family planning services and supplies, either by the public or the private health sector. In fact, despite the discontinuation of all information, education and communication activities, the provision of family planning services by Ministry of Health maternal and child health facilities and by private health clinics and practitioners were continued [9,10,12]. The findings of the first KAP survey in 1989, shortly before the official inauguration of the Iranian FPP, confirmed that 64% of urban and 31% of rural women interviewed reported using a family planning method [17].

Revived FPP based on the principles of health promotion

Announcement of population control and family planning as the leading public policy

After the ceasefire with Iraq in 1988, and then the announcement of the first 5-year economic, social and cultural development plan (1989–94) [18], the government of the Islamic Republic of Iran became aware of great demands for food, health care, education and employment. So, the population control policy was declared to be a leading priority of the government [19].

Creating a supportive environment

After convincing the top level policy-makers about the urgent need for population control, a 3-day seminar on population and development was held in Mashhad city in September 1988. Academic demographers as well as experts from the Ministries of Agriculture, Education, Economy and Health used the opportunity to stress the need for planning and control of the growth of the population and other resources of the nation. At the end of the Mashhad seminar, the Secretary of Health announced that a new FPP would be established in the Islamic Republic [10,20]. In February 1989, a seminar on Islamic perspectives in medicine was held in Mashhad and this was followed by another seminar on Islam and population policy in Isfahan in April 1989 to ensure the support of religious leaders for the programme [9]. It should be noted that over 100 articles were devoted to the topic by the major Tehran newspapers between 1988 and 1990 [21].

Goals of the new Iranian FPP

The new Iranian FPP started with 3 important goals:

encouraging birth spacing of at least 3–4 years between pregnancies;

discouraging pregnancies among women below age 18 and over age 35 years;

limiting the total number of children per family to 2–3 [12].

To further ensure the intersectoral cooperation needed, the Birth Limitation Council was set up by a cabinet decree passed in September 1990. The Council, headed by the Minister of Health, included the Ministers of Health, Education, Higher Education, Labour and Social Affairs, Culture and Islamic Guidance, and Planning and Budget as well as the head of the Civil Registration Organization. The main functions of the Council were to monitor, supervise and coordinate all government policies and activities for control of population growth [10].

The objectives of the programme designed by the Birth Limitation Council were to decrease the birth rate, decrease the population growth rate, increase the CPR among married women and to decrease the TFR. To achieve these objectives 4 main activities were planned:

organized educational programmes through schools, colleges and the mass media regarding population issues and family planning;

increasing access to free contraceptives for married couples;

providing a wide spectrum of family planning methods with appropriate quality;

conducting research on various aspects of family planning delivery and population policy [22].

A remarkable feature of the programme was attention to strategies for improving development indices such as:

improving the social and economic indices of society;

increasing the level of income and standard of living for low-income groups;

enhancing women’s participation in economic, social, cultural and political affairs;

facilitating women’s education and employment;

decreasing child mortality by expanding public health services;

extending social security and retirement benefits to all parents so that they would not be motivated to produce children as a source of security and support in old age.

The other strategies of the programme were:

increasing public awareness with respect to population issues through the mass media;

promoting male participation in family planning;

utilizing existing resources and improving the quality of family planning services;

monitoring and evaluation of the programmes [9,10,22].

In December 1988, the High Judicial Council announced that there were no Islamic barriers to family planning. This opinion allowed the Secretary of Health to finalize preparations for the Iranian FPP and order supplies of contraceptives in 1989 [9,20]. To further legitimate support and to remove continuing doubts regarding the acceptability of sterilization, in 1990 the High Judicial Council declared that sterilization of men and women was not against Islamic principles or existing laws [9,20]. The Family Planning Bill which had been prepared in 1989 was finally ratified by the parliament in May 1993. The ratification of this Bill not only removed most of the economic incentives for high fertility and large families but it also provided the necessary legal basis for the population control policy and the Iranian FPP [9].

Reorientation of family planning services

Up until 1988 family planning services were delivered through the family and school health programme of the Ministry of Health and most of the rural areas were not covered by this office. With the revitalization of the FPP a separate Department of Population and Family Planning was established. Since then, development of the primary health care network has facilitated the delivery of family planning services so that FPP services have penetrated to remote villages and become the most trusted source of contraceptive supplies and services [9,12,22]. Family planning services and free modern contraceptives; including oral contraceptives, intrauterine devices, progesterone implants and condoms are provided to the majority of rural couples via rural health houses, which form the backbone of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s well-regarded primary health care system.. These easily accessible, low-cost, community-based health houses have played a major role in the provision of family planning and other health services that has led to the narrowing of the urban–rural gap in contraceptive prevalence and other health indicators in the Islamic Republic of Iran [7].

Due to their close and continuous contact with their clients, the community health workers (behavarz) in the village health houses have been effective in educating their clients about the correct mode of use of methods such as oral contraceptives [7,9,12,22]. It should be noted that family planning services are considered an integral part of the primary health care provided by the midwives who work at the urban clinics. Clients are referred to the urban health centres for sterilization. The private sector also provides a significant portion of the family planning services obtained in urban and rural areas. Contraceptives can be bought from pharmacies, and sterilizations are carried out in private hospitals. However, these services are used primarily by middle-class urban couples and are relatively expensive when compared with those provided by the public sector [19].

Strengthening community action

Urban dwellers of lower socioeconomic level can get similarly community-based services from urban health centres, while health posts are staffed by trained women volunteers who are mainly responsible for face-to-face health promotion and educational activities [12]. The volunteers serve as intermediaries between families and government-sponsored health clinics. The women’s volunteer programme began in 1993 with 200 volunteers and now there are more than 43 000 such a volunteers throughout the country, working closely with their neighbourhood clinics [23].

Creating personal skills

The Iranian FPP focuses on 2 main activities: education and service provision. The educational activates includes premarital education of high-school and college students as well as for soldiers, couples contemplating marriage and couples after marriage. Single people can also obtain services and family planning education [24].

Achievements of the revived Iranian FPP

As Figure 1 shows, both the population growth rate and TFR showed a declining trend from the first census in 1956 until the latest figures in 2006, but the greatest decline was in the period 1986–96, after the inauguration of the active FPP.

The family planning indicators were also improved during the years following the implementation of the revived FPP. As Table 1 shows, the highest total CPR and modern CPR were in 1996 and 1997 and no further improvements were seen in these indicators. There was also no significant decrease in the unwanted pregnancy rate during the last decade.

Recent approaches and interventions

The department of population and family planning of the Ministry of Health is not only continuing and strengthening previous approaches but has also began to implement more intervention and evaluation programmes [25]. A few recent activities include:

establishment of family planning research centres in the universities of medical science;

launching vasectomy educational and vasectomy provision centres, using male volunteers in workplaces;

promoting the FPP in village cooperatives and workers’ health houses, in Afghani and Iraqi refugee camps, among families supported by the Imam Charity Committee and among prisoners and police forces;

educating parent–teacher associations about overpopulation;

establishing an information, education and communication centre for family planning in Tehran;

monitoring and evaluation of the health provision services;

developing family planning standards and instruction techniques;

making population change predictions using prediction software.

The key targets of the office are the achievement of a TFR around the replacement level of 2.1; calculating population change predictions and unwanted pregnancy rates for different areas; and planning, implementing and evaluating the intervention programmes based on evidence of factors associated with unwanted pregnancy [24].

Discussion

Several studies have been undertaken to review and analyse the population transition and fertility rate changes in the Islamic Republic of Iran [7–12,19,20,22]. A number of studies showed that fertility transition in the country was associated with changes in social, economic and political conditions. For example, demand for fewer children due to the decline in infant mortality rate could have an important role [19] or increasing literacy rates and education levels, particularly for women, delays the initiation of pregnancy [9,22]. Modernization [26] and urbanization [27] are also mentioned as important contributors to the sharp decline of fertility rates and population growth.

There is evidence that the decline in the population growth rate with increasing development has been more pronounced in the Islamic Republic of Iran than other countries in the region. Among 5 Muslim Asian countries (Algeria, Turkey, Bangladesh and Indonesia and Islamic Republic of Iran) fertility has fallen farthest and fastest in Islamic Republic of Iran [28]. In all 5 cases, the government’s FPP started as a response to concern about excessive population growth that arose as part of an effort to stimulate social and economic modernization [28]. The Iranian fertility transition clearly accelerated after the inauguration of the new FPP in 1989 and therefore it can be assumed that the Iranian FPP was an important factor in the fertility transition [19,22].

Increased age of marriage and reduction in the proportion of women ever-married, especially during the period 1986–96, are also considered as important factors contributing to the fertility transition [19]. However, about 85% of the decline in fertility has been attributed to the decrease in marital fertility during the period 1986–96, and changes in nuptiality patterns were responsible for only 15% of the decline. This suggests that Iranian women have controlled their fertility behaviour within marriage by controlling the starting, spacing and stopping of childbearing [7]

All the above factors have contributed to the success of FPP in the Islamic Republic of Iran. According to the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion in 1986 the principles of health promotion action for any aspect of health including family planning requires the following elements: building healthy public policy; creating a supportive environment; strengthening community action; developing personal skills; and reorientation of health services [29].

Building healthy public policy required that policy-makers in all sectors in the country were aware of the health consequences of their decisions on uncontrolled overpopulation. In this regard, in early 1989, the Iranian government, alarmed about the risk of overpopulation, announced that “none of the government’s development and welfare programmes is likely to succeed without a serious FPP”.

Creating a supportive environment was made possible in the Islamic Republic of Iran by:

holding several seminars at the beginning of the programme to convince religious and other opinion leaders to support the programme;

planning for improving the social and economic indices such as increasing income levels in the population;

empowerment of women through women’s education and employment;

decreasing child mortality;

extension of social security and retirement benefits;

legislation for removing obstacles for family planning such as benefit limitations for the fourth child and a higher budget for the FPP;

increasing public awareness through the mass media, especially television, and supportive articles in magazines and daily newspapers.

Strengthening community action has been achieved through seeking help for community-based education and distribution of contraceptives by female volunteers. Involving nongovernmental organizations and the private sector for promotion of the programme were also part of the Iranian FPP.

Developing personal skills is achieved through face-to-face counselling with clients by midwives in urban health centres or by female volunteers in urban areas and behvarz in rural areas. Education of couples in pre- and post-marriage classes in health centres and community education in schools, colleges, army, workplaces and through mass media were all performed.

Reorientation of the services included establishment of an independent Department of Population and Family Planning in the MOHME; equipping family planning sections of primary health care centres with a variety of free contraceptives; establishment of free vasectomy facilities at primary health care services; and offering mobile vasectomy and tubectomy services for remote areas.

It should be notable that the international declarations on the principles of health promotion have been refined several times since 1986, and the latest one, the Bangkok Charter for Health Promotion in 2005, complements and builds on the values, principles and action strategies of health promotion established by the Ottawa Charter [30]. These refinements should be considered in the new approaches to FPP promotion in the Islamic Republic of Iran, because the global context of health promotion has changed markedly since drawing up the Ottawa Charter. It should be noted that because of the high fertility rates of the early 1980s, there will be a large increase in the proportion of women of childbearing age during the next decades. So, the country faces the prospect of a “baby boom” within the coming decades [19]. Thus, further developments to the Iranian FPP based on the new approaches should be designed.

There is evidence that the FPP in the Islamic Republic of Iran has led to a change of fertility behaviour among Iranian couples. From the perspective of the health belief model the FPP was successful in helping people to perceive the threat of overpopulation and the benefits of the programme, to overcome barriers to healthy behaviour as well as developing the perceived self-efficacy necessary for changing behaviour [31,32].

The Iranian FPP can be an appropriate model for other aspects of reproductive health promotion, such as women’s and adolescents’ health, promotion of male participation in reproductive health, promotion of sexual health and prevention of STIs/HIV/AIDS and so on, in this and other countries especially in the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR).

There were no improvements in modern CPR in Islamic Republic of Iran after 1996. There was also no significant decrease in the unwanted pregnancy rate during these years. According to the Iranian 2000 DHS, 26% of married women in the country have an abortion in their lifetime and the abortion rates were higher in provinces where modern contraceptive use rates were lower [33]. Although the Islamic Republic of Iran reached the desire TFR and population growth rates in these years, improving modern CPR is necessary for reducing the rate of unwanted pregnancies [34]. In this and many other EMR countries induced abortion is prohibited or is legal only for saving the mother’s life [33]. Yet unwanted pregnancies can lead women to risk unsafe illegal abortions. It has been demonstrated that in the Islamic Republic of Iran, unwanted pregnancy was one of the most important risk factors for induced abortion, with an odds ratio of 8.84 [35]. In Islamic countries of the EMR, prevention of unwanted pregnancy by promotion of modern contraceptive use may help to prevent these unwanted pregnancies. The Iranian FPP needs a greater emphasis on promotion of modern contraceptive use by providing high-quality modern contraceptives and counselling to decrease unwanted pregnancies and avoid the need for women to resort to unsafe abortion with all its negative outcomes.

Recommendations

Nowadays in the Islamic Republic of Iran, as in other countries, the quality of family planning services is considered a global concern [36]. Assessments of quality of care in the Iranian FPP services have demonstrated the presence of adequate facilities and equipment and trained personnel, together with high satisfaction of clients with the services. However, clients’ knowledge about the selected methods were only moderate. Therefore, it is time for intervention programmes to improve the family planning counselling process of clients [37,38]. It is also time to improve male involvement in reproductive health programmes including FPP in the Islamic Republic of Iran, as research shows that although men have positive attitudes about participation in reproductive health programmes including FPP [39,40] there are still a minority who believe that men are the main decision-makers in family planning [41]. It should be noted that one of the most important characteristics of the Iranian FPP at the start was that it was the only one in the EMR which promoted both male and female sterilization [42].

References

- A holistic approach underpins the Islamic Republic of Iran’s success in family planning. United Nations Population Fund [online factsheet] (http://web.unfpa.org/countryfocus/iran/family.htm, accessed 23 December 2011).

- Preliminary report on the Demographic and Health Survey. Tehran, Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Deputy of Health, 2000 [in Farsi] (http://www.fhp.hbi.ir/FHPPages/MainOffice/DHS-REP.HTM, accessed 23 December 2011).

- Population Division, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World contraceptive use 2003. United Nations [online factsheet] (http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/contraceptive2003/WallChart_CP2003.pdf, accessed 23 December 2011).

- Annual book of statistics. Tehran, Statistical Center of Iran, 2005 [in Farsi]. (http://amar.sci.org.ir/index_e.aspx, accessed 23 December 2011).

- [Demographic indicators of Iran, 1956–1996]. Tehran, Statistical Center of Iran, 1998 [in Farsi].

- Monitoring ICPD goals—selected indicators. In: The state of world population 2005. Geneva, United Nations Population Fund, 2005.

- Abbassi-Shavazi MJ. Effects of marital fertility and nuptiality on fertility transition in the Islamic Republic of Iran, 1976–1996. Canberra, Australian National University, 2004 (Working Papers in Demography No. 84).

- Roudi F. Iran’s revolutionary approach to family planning. Population Today, 1999, 27:4–5.

- Mehryar AH et al. Repression and revival of the family planning programme and its impact on the fertility levels and demographic transition in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Cairo, Economic Research Forum for the Arab Countries, Iran and Turkey, 2001 (Working Paper 2022).

- [History of family planning in Iran]. Tehran, Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Deputy of Health, 2009 [in Farsi]. (http://www.fhp.hbi.ir/fhppages/TanzimOffice/TanzimOfficeHistory.htm, accessed 23 December 2011).

- Aghajanian A. Population policy, fertility and family planning in Iran. In: Mahadevan K, ed. Fertility policies of Asian Countries. New Delhi, Sage Publications, 1989.

- Mehryar AH et al. Iranian miracle: how to raise contraceptive prevalence rate to above 70% and cut TFR by two-thirds in less than a decade? Tehran, Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Institute for Research on Planning and Development, 2001 (http://www.iussp.org/Brazil2001/s20/S20_02_Mehryar.pdf, accessed 23 December 2011).

- Nortman D, Hofstatter E. Population and family planning programs: supplementary tables to the 9th edition of the Fact-book. New York, Population Council, 1979 (Working Paper Special Series No. 2).

- Family planning graphs, 2009. Tehran, Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Family Planning Office, 2009 (http://www.fhp.hbi.ir/FHPPages/HTML-slides/fp-graphs.htm, accessed 23 December 2011).

- [Fertility study of Iran 1977]. Tehran, Statistical Center of Iran 1987 [in Farsi].

- [Annual book of statistics of Iran]. Tehran, Statistical Center of Iran, 1990 [in Farsi].

- Malek Afzali H. [Knowledge, attitude and practice of women about family planning]. Tehran, Ministry of Health and Medical Education, 1989 [in Farsi].

- [The first plan of economic, social and cultural development of the Islamic Republic of Iran (1989–1993) Bill, Appendix I]. Tehran, Plan and Budget Press, 1989 [in Farsi].

- Aghajanian A, Merhyar AH. Fertility, contraceptive use and family planning programme activity in the Islamic Republic of Iran. International Family Planning Perspectives, 1999, 25 (2):98–102.

- Aghajanian AA. New direction in population policy and family planning in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Asia-Pacific Population Journal, 1995, 10(1):3–20.

- Ayazi MA. [Islam and family planning]. Tehran, Daftar Nashr Farhang Islami, 1994 [in Farsi].

- Aghajanian A. Family planning programme and recent fertility trends in Iran. MEASURE evaluation. Chapel Hill, North Carolina, Population Center of University of North Carolina, 1998:1–60.

- Roudi F. Iran’s family planning programme: responding to a nation’s needs. Washington DC, Population Reference Bureau. 2002:1–8.

- Khoshbeen S et al. Population and family planning. Tehran, Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Deputy of Health/United Nations Population Fund, 2002 [in Farsi] (http://www.fhp.hbi.ir/e-books/B-FAMILYPLANNING.pdf, accessed 23 December 2011).

- [Mission of family planning office]. Tehran, Ministry of Health and Medical Education. Deputy of Health, 2009 [in Farsi].

- Paydarfar A, Moini R. Modernization process and fertility change in pre- and post-Islamic Revolution of Iran. Population Research and Policy Review, 1995, 14:71–90.

- Sheykhi MT. The socio-psychological factors of family planning with special reference to Iran: a theoretical appraisal. International Sociology, 1995, 10:71–82.

- Jones E, Westoff CF. Executive summary—fertility decline in Muslim countries. Washington DC, Population Resource Center, 2003

- Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. First International Conference on Health Promotion, Ottawa, 21 November 1986. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1986 (WHO/HPR/HEP/95.1)

- Tang CK, Beaglehole R, Leeuw E. Sixth Global Conference on Health Promotion Bangkok, August 2005. Health Promotion International, 2006, 21(S1):10–14.

- Rosenstock IM. The health belief model: explaining through experiences. In: Glanz K, Lewis FM, eds. Health behavior and health education: theory and practice. Oxford, Jossy-Bass Publishers, 1990.

- Theory at a glance: a guide for health promotion practice. Atlanta, Georgia, National Institutes of Health, 2005 (NIH Publication No. 05-3896).

- Dabash R, Roudi-Fahimi F. Abortion in the Middle East and North Africa. Washington DC, Population Reference Bureau, 2008.

- Singh S et al. Abortion worldwide: a decade of uneven progress. New York, Guttmacher Institute, 2009.

- Majlessi F, Forooshani AR, Shariat M. Prevalence of induced abortion and associated complications in women attending hospitals in Isfahan. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 2008, 14(1):103–109.

- World Health Organization. Strategy to accelerate progress towards the attainment of international development goals and targets related to reproductive health. Reproductive Health Matters, 2005, 13:11–18.

- Simbar M et al. Quality assessment of family planning services in urban health centers of Shahid Beheshti Medical Science University. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance Incorporating Leadership in Health Services, 2006, 19:430–442.

- Nakhaee N, Mirahmadizadeh AR. Iranian women’s perceptions of family-planning services quality: a client-satisfaction survey. European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care, 2005, 10:192–198.

- Modarres Nejad V. Couples’ attitudes to the husband’s presence in the delivery room during childbirth. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 2005, 11:828–834.

- Tavakoli R, Rashidi-Jahan H. Knowledge of and attitudes towards family planning by male teachers in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 2003, 9:1019–1025.

- Rakhshani F, Niknami S, Ansari Moghaddam AR. Couple communication in family planning decision-making in Zahedan, Islamic Republic of Iran. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 2005, 11:586–593.

- Roudi F. Iran’s revolutionary approach to family planning. Population Today, 1999, 27:4–5.

- Bharier J. A note on population of Iran. Population Studies, 1968, 22:273–279.

- World health statistics 2009. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2009:133–134.