H. Behdjat,1 S.B. Rifkin,2 E. Tarin3 and M.R. Sheikh4

دور جديد للمتطوعات الصحيات في أرياف جمهورية إيران الإسلامية

حسين بهجت، سوزان ريفكين، إحسان الله تارين، مبشر رياض شيخ

الخلاصـة: نفذ الباحثون من المركز الوطني لإدارة الصحة العمومية مشروع بحث ميداني في تبريز، إيران، لاختبار الفرضية التالية: إن قدرة المتطوعات الصحيات على دعم التحسينات الصحية من خلال التـركيز على مساهمة المجتمع وتمكينه بواسطة التيسير على المجتمعات للتعرف على مشكلاتها وحلها، أكبر من الاقتصار على تقديم المعلومات حول المشكلات الصحية. وقد قدم الباحثون التدريب على أساليب المشاركة إلى المتطوعات الصحيات في مجالات ارتيادية. وقد حصلوا على نتائج تشير إلى أن هناك بيِّنات على أن الناس في البيئة المحلية يمكنهم التعرف على احتياجاتهم الصحية، والعمل على تلبيتها، وطلب المزيد من المعلومات من أرباب المهن الصحية لتحسين صحتهم. وتمس الحاجة إلى البحوث لتقييم كيف يمكن النهوض بهذه التجربة الارتيادية وكيف يمكن الحفاظ على الحماس المبدئي.

ABSTRACT An action research project was carried out by a team from the National Public Health Management Centre in Tabriz, Iran to test the following hypothesis: Health Volunteers are more able to support health improvements by focusing on community participation and empowerment through facilitating communities to define and solve their own problems than by only providing information on health problems. Training on participatory approaches was given to Women Health Volunteers (WHV) in a pilot area. The results gave evidence that local people could identify and act upon their own health needs and request more information from professionals to improve their own health. Further research is needed however to assess how the pilot can be scaled up and how initial enthusiasm can be sustained.

Nouveau rôle des femmes agents de santé bénévoles dans les zones urbaines de la République islamique d’Iran

RÉSUMÉ Un projet de recherche-action a été mené par une équipe du centre national de gestion sanitaire publique de Tabriz (Iran) dans le but de vérifier la validité de l’hypothèse suivante : les agents de santé bénévoles ont plus de chances de favoriser l’amélioration de la santé s’ils axent leurs efforts sur la participation et l’autonomisation communautaires en permettant aux populations locales de définir et de résoudre leurs propres problèmes qu’en se contentant de leur fournir des informations sur les problèmes de santé. Une formation aux méthodes participatives a été organisée à l’intention du programme des femmes agents de santé bénévoles dans une zone pilote. Les résultats ont montré que les populations locales pouvaient recenser et prendre en charge leurs propres besoins sanitaires et demander davantage d’informations aux professionnels pour améliorer leur propre santé. Il convient néanmoins d’approfondir la recherche afin d’évaluer les possibilités d’élargir le projet pilote et de maintenir l’enthousiasme initial.

1National Public Health Management Centre, Tabriz, Islamic Republic of Iran.

2London School of Economics, London, United Kingdom (Correspondence to S.B. Rifkin:

3World Health Organization, Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran.

Received: 27/05/07; accepted: 13/11/0

EMHJ, 2009, 15(5):1164-1173

Introduction

There is increasing recognition that policy-makers need more information than that provided by the rigid hierarchies of randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews [1].

This view supports the role of action research in providing evidence for health policy and programmes. Action research is research that:

- is educative.

- is focused on individuals as member of social groups.

- is problem focused, context specific and future oriented.

- is involved with a change intervention.

- is aimed at improvement and involvement.

- is a cyclical process in which research, action and evaluation are interlinked.

- is based on a research relationship in which those involved are all participants in the change process [2].

The purpose of this paper is to show the application of action research to inform policy-makers about potential changes in health care delivery. It describes and analyses a pilot project that refocuses the tasks of urban Community Health Workers (CHWs) in the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Background

In the 1990s in the Islamic Republic of Iran, a cadre of CHWs, called Women Health Volunteers (WHVs), was created to meet urban needs; they were complementary to the rural CHWs, called beharvz [3]. There were 5596 WHVs serving 171 urban health centres in 2004 [4]. They were seen as an interface between the health services and the people, largely migrants from rural areas and living in slums and peripheral urban areas.

Urban health problems are different from those in rural areas and disease patterns reflect more closely peoples’ choice of lifestyle. In addition, people in urban areas have a much wider choice of health services and do not keep such close contact with government health units. A result of this is that there has been a shift in emphasis to health promotion and empowerment where health staff are encouraged to play a role of agents of change facilitating people’s health choices and encouraging self-reliance.

Health promotion has increasingly gained recognition as a means to improve health service utilization [5]. The move from information provision about health matters to health promotion and empowerment has highlighted issues such as health as a human right [6] and the development of participatory approaches to involve local people and communities in decisions about health care [7].

Methods

Development of the intervention

In recognition of the above-mentioned issues of health promotion to move from mobilization to empowerment, the WHO office in the Islamic Republic of Iran supported a research pilot project as a component of the Second Primary Health Care and Nutrition Project. The National Public Health Management Centre (NPMC) in Tabriz was chosen as the institution to carry out the project. The Project was conceived as an action research project.

It began with the formation of a Research Team composed of faculty members of the NPMC and officers of the provincial health centre. As a first step, the team reviewed the strengths and weaknesses of the volunteer programme focusing on CHWs experiences by carrying out a literature review of the published literature.

The next step was to do a survey in Tabriz to find out how WHVs viewed their work. The participants were selected purposely through a 2-stage process. First, 20 urban health centres in Tabriz city were selected randomly out of a total of 27 such centres. Then, out of the WHVs affiliated with each of the 20 health centres, 1 WHV was selected randomly, making a total of 20. These WHVs were approached regarding their willingness to participate in the proposed focus group discussions (FDGs)and a possible intervention coming from the research. Of the 20, 18 agreed to participate, while 2 declined. The 18 WHVs were divided into 2 groups each comprising 9 WHVs and FGDs were held [7]; each group held 3 FGDs making a total of 6 FGDs.

The principal investigator of the research project conducted the FGDs. One FDG addressed the concepts of health including the definition of health, dimensions of health and health determinants. The second FDG examined the WHV programme and dealt with reasons for becoming a WHV and satisfaction with the job, and elicited suggestions about any new role they would like to play; The third FDG discussed the topic of community participation and how WHVs could contribute to the health of families, what role they could play to improve the health of men (considering that all WHVs are women) in the area of their residence, and how they could promote and improve their skills. A member of the research team designated as note-keeper recorded the discussion verbatim. Another member of the research team observed the group and recorded the observations. After each FGD session, with the help of the note-keeper and observer, the records of the FGDs were discussed and analysed by the research team. This information was the basis of the project design.

The major conclusions of the FDGs were as follows.

- The participants knew the concept of health and its determinants, although had limited understanding of the social dimension of health. They had adequate knowledge about diseases, but only some could identify environmental factors as determinants of health.

- They had joined the programme out of interest and the possible incentives they expected to receive. However, most of them were not satisfied with their tasks and thought they were not being useful. They were prepared to accept a new role to enrich their work.

- All the participants believed they could help families in improving their lifestyle and that they could influence men through their wives and sisters. In order to be able to do so they were willing to learn new skills, especially in the area of community participation.

Key informant interviews were also conducted by the principal investigator with district and provincial level officials who were involved in the WHV programme. The questions included: (i) who in the urban health centres is responsible for managing the WHV programme? (ii) to what extent do the health workers in urban health centres cooperate with WHVs? (iii) what is the impact of WHVs on the health of the population? (iv) what do you suggest to improve the WHV programme? Notes were taken and the contents of the interviews were reviewed several times in the context of the WHV programme and the design of the proposed intervention.

The results of the interviews showed the following.

- A health worker, often a family health technician, is assigned to work with WHVs as tutor/ mentor. However, due to the shortage of health staff and rapid turnover of staff it was becoming increasingly difficult to have someone in each urban health centre to devote adequate time to the WHVs. Therefore, often it is either the interest of an individual staff member or the person in charge of the health centre who is keeping the programme operating.

- The health workers in the health centre meet with WHVs once a week for training on subjects specified in their curriculum. Apart from that, there is no active work relationship. While the WHVs would like more attention from their tutors, there were few health workers who were interested in investing in WHVs.

- The WHVs in their current role do not have a significant impact on the health of the population.

- Almost all key informants expressed their dissatisfaction with the performance of the programme and liked the idea of radical changes in its organization. They suggested enhancing the role of WHVs. In addition, they felt that since community participation for health is a technical issue, both health workers and WHVs needed training and skill building. They also felt that the WHVs should be free to define interventions in partnership with the people with whom they had contact and urban health centres should support the process. Only volunteers should be selected as WHVs, so that there are no subsequent expectations.

The research team incorporated the key ideas gathered from interviews with key informants and the results of the FDGs into the design of the project. The process of planning also helped to create a rapport and working relationship with the all participants that was helpful in implementing the project interventions

The research design was a result of an iterative process to define an intervention to change the role of WHVs. After reviewing the information gathered from the literature review and the survey, a project was developed to evolve a strategy for using the WHVs programme to harness greater involvement of communities in their own health. Specifically, an action research project was designed to test the hypothesis that health volunteers are more able to support health improvements by focusing on community participation and empowerment through facilitating communities to define and solve their own problems than by only providing information on health problems. The WHVs in this project were to act as the facilitators or animators instead of just being the informers. WHO assisted the project by providing technical support and funds. The pilot project followed the format of action research.

Training

To pursue this objective, training courses were developed. Training was done in a cascade manner. The first course was held for 3 days at the NPMC to acquaint the research team and provincial and municipal health managers with the skills and knowledge that was necessary to carryout this research. The course was organized and facilitated by the principal investigator at the NPMC and was based on a textbook on participatory approaches [7]. One of the author’s of the book conducted the training. With the support of the provincial and municipal health authorities, a pilot area was selected to carryout the project. This area was based in the Azadi Health Centre where staff and WHVs were enthusiastic in their support for the project.

The second training (a 2-day workshop) was done for the health staff by the principal investigator and the final training (1 day per week for 2 weeks, to accommodate family obligations) was done for the WHVs attached to the health centre using materials from the textbook.

The training included defining participation and its importance in health services, identifying the determinants of health particularly those related to lifestyle and their amenability to change, and learning methods and tools for participatory planning. Participants were introduced to the tools for health needs assessment, priority setting and visioning of future developments in the community in which they live. Practical sessions were also organised in the field for both the staff and WHVs. In this training 8 out of the total of 33 WHVs affiliated with the health centre dropped out as their family circumstances would not allow commitment to this exercise.

Activities

After the training each of the WHVs purposively selected a group of households from those for whom they were responsible. The women from these households who could spare time were brought together to undertake a participatory needs assessment. The Iranian culture would not allow the WHVs to include men in their cohort. The WHVs introduced the group to the concept of the assessment and worked with them to undertake a mapping of their area. After the women had drawn the maps, they used the maps to identify problems facing their neighbourhood. They then used a ranking system based on a matrix for prioritizing the problems.

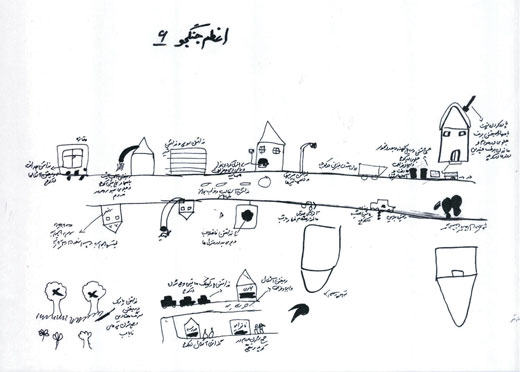

The groups produced another matrix as a tool for priority setting. They drew a table, where a projection was made describing what would be the outcome of a particular problem in different circumstances with the objective of defining how problems might be solved. The staff at the urban health centre worked as tutor/mentor and assisted in organising logistics and providing clarifications to WHVs. Figure 1 is an example of a map of one of the neighbourhoods. Table 1 is the pairwise ranking matrix that identified the major problems in the neighbourhood. Table 2 shows the priority ranking of problems. Table 3 shows the visioning matrix that helped to identify activities to solve the identified problems. A visioning matrix enables participants to take priority problems and then analyse how the situation was in the past, how it is in the present, what the situation will be without any interventions and finally what the ideal situation would be if action is taken.

Figure 1 Map of one of the neighbourhoods constructed by the women of the community with the guidance of Women Health Volunteers

Results

After the training, neighbourhood groups made plans of action and decided upon activities to solve their problems. The problems were listed and then categorized into challenges where: (i) the WHVs were able to provide a solution; (ii) government help was needed; (iii) it was not possible to make any intervention. The WHVs were encouraged to focus on the issues where they themselves could intervene and bring about some change.

Perhaps the most dramatic example of problem-solving was the group that decided to reclaim the neighbourhood park that was occupied by drug addicts,making the place unsafe for others. The WHVs and their team mobilised local women to come to the park every day in the morning to take exercise by walking for 1 hour in the park. With sight of over 50 women in dressed in chador, the traditional long black garment that covers the entire body, walking in the area had the desired effect of removing the drug addicts. Such activity had a number of positive spin-offs. The first was the park became safe as an area for recreation and social gatherings. In addition, the women who did the daily walk recognised the value of such exercise as a contribution to their health. This was particularly true for the women over 50 years. In a meeting with the project team, one elderly woman came with her test reports to demonstrate how the exercise has helped reduce her blood glucose and cholesterol. Their participation created a demand for more information and understanding about health for the elderly. As a result, talks about this topic were given by the WHVs, who were briefed by the health staff. In addition, the WHVs prepared pamphlets on requested topics. Twelve sessions were held to provide health information on different topics related to healthy life skills. Each session was attended by about 70 participants. This activity was sponsored by the Ministry of Health and Medical Education as well as the Ministry of Welfare.

Another positive spin-off was that the park, having been reclaimed from addicts, was used by the children for healthy activities such as riding bicycles.

Another activity that emerged from the participatory needs assessment was one to deal with the problem of many young men roaming the streets. To help overcome this problem a book reading competition was organized. Over 70 young people participated in the competition, at the end of which they responded to questions about the book they had read. A ceremony was organized and the winners were awarded prizes that were arranged by the local office of primary health care. The group is now planning to establish a library and hold such competitions on a regular basis.

Drug addiction among youth was identified as a grave social problem and a priority by many who participated in the health needs assessment exercise. To deal with this concern, the group asked the husband of a WHV who worked in the Social Welfare Department to help. The Social Welfare Department provided a teacher/psychologist to hold meetings with youth to identify alternatives to drug use. A local mosque provided classroom space to hold these meetings.

In cases where government help was needed, WHVs, working with the participants, identified the suitable department or organization. For example, the erratic collection of garbage was an issue that required the involvement of the municipality. Also, there were no designated places for dumping garbage. The WHVs met with the deputy mayor and experts from the local municipality with the project team present. The issue was discussed and a schedule for garbage collection was agreed. While the WHVs took the responsibility to inform the community about the schedule and to motivate them to deposit garbage in the designated locations using plastic bags, the municipality was to ensure its collection according to the schedule.

For the issues where the WHVs could not make any specific intervention, some measures to alleviate the effects of the problem were suggested. For example, a group of WHVs living near the airport identified the sound of airplanes landing and taking off as a nuisance, particularly waking children at night. While considering the solutions to this problem, it was suggested that families with children could use ear plugs in order to reduce the sound.

Working on the project provided opportunity for WHVs to come together and in this process to develop an atmosphere of friendship and trust. As a result, they created a voluntary fund to which each participant contributes every month. The collection is disbursed on rotation to one of the fund members, thus providing them opportunity of capital investment.

In addition, there are a number of planned activities that have been identified but not yet implemented. For example, as unemployment was identified as a priority problem, a group of WHVs is considering establishing a centre for handicrafts. Another intervention being investigated is to encourage families to use liquid oil instead of solid oil to reduce the health effects of using the latter; a group of WHVs is planning to organize briefing sessions for families. Likewise, the low fish consumption was assessed through participatory appraisal, and the reason for this was found to be because housewives did not know how to cook fish. Thus another group of WHVs is planning to hold cooking classes.

Discussion

The action research project set out to investigate whether WHVs would be more effective as facilitators than informers to improve health in urban communities. The results presented above show that: 1) WHVs can facilitate participatory needs assessments in which local people collect information, analyse results and make action plans to address priorities identified in the needs assessments and 2) based on these assessment, local people can plan and execute activities that lead to health improvements. The evidence presented here suggests that participatory approaches to health promotion can change lifestyle habits among local urban neighbourhood communities to improve both individual and community health.

From the above description of this pilot activity, it is also possible to identify factors that produce these results. The following seem to be the most important.

Leadership and inspiration

In the action research project, leadership and inspiration was provided by the Principle Investigator and the health centre staff who gave much time, personal contribution in material and sometimes money and continual advice and inspiration to the WHVs. Without their commitment and enthusiasm, such results would not be possible.

Support of external institutions

Support of the action research was also provided by the Provincial Health Office and the NPMC. The Health Officer in charge of the WHV programme was part of the Research Team. As well as providing support, NPMC also convened a final ceremony at the end of the pilot activity where the WHVs were given certificates and blankets as a gift for their good efforts. WHO’s contribution included the initiation and financing of the research and the dissemination of the findings.

Successes

Another major factor was the incremental successes gained by each participant during the project. The WHVs gained knowledge and confidence when they found out they could do the mapping, identify priorities and create solutions. They became more confident when they were able to transfer these skills to other lay women in the community and to make a plan of action to solve the problems. When their plan of action succeeded (the example of regaining the park for family use), their ability to exercise control over problems in their lives was confirmed. The experiences they had and the process of identifying and succeeding in achieving objectives moved their participation in the project from simply mobilization to transformation and empowerment of the community.

Generalizability and sustainability

The project was run as an action research pilot project. What the evidence shows is that changing WHVs from mere informers to facilitators for participation of local people in health improvements is possible. However, this experience cannot be generalized. Resources were mobilized that might be difficult to find in other areas. The support of WHO and NPMC are 2 such resources. Their support was not only in materials and money but also in the recognition brought to the project by the backing of 2 important institutions.

In addition, there is a question of the sustainability of the programme. While relatively few resources were placed in the pilot project itself, considerable resources were placed in the research project, mainly on researchers in the NPMC and external consultants. While this external expenditure need not be incurred again in replication, it must be recognised that the support of WHO and NPMC gave credibility and recognition to this effort. It is not clear how important such a catalyst is to sustaining efforts.

Scaling up

The final question is whether such a project can be scaled up. Past experience suggests that in the field of health, participatory approaches are often conceived as interventions. This view suggests that there is a “gold standard” for replication. Evidence however shows that this is an inappropriate framework in which to assess and value these approaches. Because communities have different cultural values and historical roots, it is more useful to assess community participation as a process. WHO, after reviewing the result, showed interest in expanding this approach to other areas. The action research approach would allow this to be done in a systematic manner, recording lessons for others to use in expansion.

There is much evidence to show that these approaches have produce marked changes in health and health status in small-scale programmes [8]. Recent experience in Ghana suggests that community-based approaches which include participation can be replicated on a national scale [9]. These examples show that changes come about as a process rather than a specific intervention that is reliable and replicable. It is the factors identified above—leadership and inspiration, external support and incremental successes—that build a foundation for positive changes. To date, there is no formula to ensure that specific actions will bring about desired outcomes [10,11].

A key to understanding these processes is the examination of attitudes and behaviours of all the actors involved in community-based programmes [10]. Local community people change attitudes and behaviours that lead to a sense of programme ownership and sustainability. However, a major contribution to this change is the attitudes and behaviours of the professionals involved in health promotion. Professionals need to develop partnerships with local communities built on mutual respect and mutual contributions to programmes. These changes in behaviours and attitudes take time and respond to individual circumstances.

As an action research project, the pilot project provides evidence about participation that would not be possible to obtain in a more rigidly controlled intervention project. In addition, it enabled all participants (researchers, collaborators, health staff and intended beneficiaries, WHVs and community members) to be involved in a learning process by helping to define the project and benefit from the results.

It is now recognised that health improvements are as much a result of what people do to and for themselves as a result of biomedical interventions. The challenge is to identify processes whereby individuals and communities find ways to follow a course of action to produce better, sustainable health. Action research makes an important contribution to addressing this challenge.

References

- Pang T. Evidence to action in the developing world: what evidence is needed? Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 2007, 85(4):247.

- Hart E, Bond M. Action research for health and social care: a guide to practice. Buckingham, Open University Press, 1995.

- Shapour K. Primary health care networks in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 2000, 6:4:822–5.

- Rifkin SB. Review of the findings of a health service utilization study for developing a model of community participation in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Cairo, World Health Organization Regional Office for the Mediterranean, 2005 (document EM/HEC/008/E/R/04.06).

- Laverack, G. Health promotion practice: power and empowerment London, Sage, 2004.

- Health and poverty reduction strategies. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2005 (Health and Human Rights Publication series, No. 5).

- Rifkin SB, Pridmore P. Partner in planning: information, participation and empowerment London, Macmillan Education, 2001.

- Taylor-Ide D, Taylor C. When communities own their future. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

- Nyonator FK et al. The Ghana community-based health planning and services initiative for scaling up delivery innovation. Health policy and planning, 2005, 20(1):1–25.

- Rifkin SB. Paradigms lost: Toward a new understanding of community participation in health programmes. Acta tropica, 1996, 61:79–92.

- Tarin EU, Thunhurst C. Community participation – with provider collaboration. World health forum, 1998, 9:72–5.