I.A. Al-Khatib1 and S.M. Al-Mitwalli 1

الجودة المكروبيولوجية وسياسة جمع العينات لمنتجات الألبان في منطقتي رام الله والبيرة، بفلسطين

عصام أحمد الخطيب، سوزان محمد المتولي

الخلاصـة: هدف الباحثون إلى التعرُّف على التلوُّث بالجراثيم أو بالعوامل الممرضة في عيّنات من منتجات الألبان جمعها المفتشون المسؤولون عن صحة البيئة في وزارة الصحة الفلسطينية في الفتـرة من 2001 إلى 2004. وقد جُمعت 722 عينة من منتجات الألبان بشكل عشوائي من مصادر مختلفة في رام الله والبيرة؛ وكانت النسبة المئوية للنماذج غير المقبولة في السنوات جميعها: 23% بسبب عدد الجراثيم الهوائية، و21% بسبب عدد القولونيات، و15.2% بسبب عـدد القولونيات البرازية، و1% بسبب عدد العنقوديات الذهبية، و10.3% بسبب الفطور، و2.3% بسبب الخمائر، و14.3% بسبب الإيشريكية القولونية. وكانت العينات المفحوصة سلبية لأنواع السلمونيلا، كما ارتفع عدد الجراثيم الهوائية بشكل مستمرّ بين عامَي 2001 و2004.

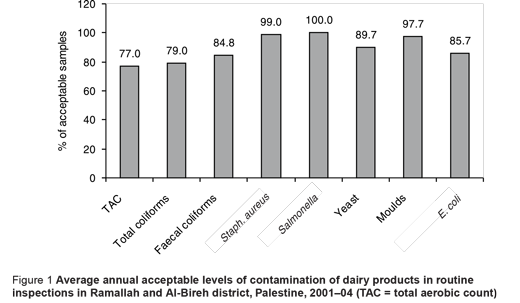

ABSTRACT We aimed to identify bacterial pathogens/contaminants in dairy product samples collected by environmental health inspectors of the Palestinian Ministry of Health from 2001–04. A total of 722 samples of dairy products were randomly collected from different sources in Ramallah and Al-Bireh district. The percentages of unacceptable samples for the combined years were: 23.0% for total aerobic count, 21.0% for total coliforms, 15.2% for faecal coliforms, 1.0% for Staphylococcus aureus, 10.3% for moulds, 2.3% for yeasts and 14.3% for Escherichia coli. All the examined samples tested negative for Salmonella spp. Total aerobic counts rose continuously between 2001 and 2004.

Qualité microbiologique des échantillons de produits laitiers et politique en matière de prélèvement dans le district de Ramallah et Al-Bireh (Palestine)

RÉSUMÉ Notre objectif était d’identifier les agents pathogènes bactériens/contaminants dans les échantillons de produits laitiers prélevés par les inspecteurs des services d’hygiène de l’environnement du ministère de la Santé palestinien entre 2001 et 2004. Au total, 722 échantillons de produits laitiers ont été prélevés de façon aléatoire auprès de différentes sources dans le district de Ramallah et Al-Bireh. Les pourcentages d’échantillons inacceptables pour le total de la période étaient les suivants : 23,0 % pour le dénombrement de bactéries aérobies totales, 21,0 % pour les coliformes totaux, 15,2 % pour les coliformes fécaux, 1,0 % pour Staphylococcus aureus, 10,3 % pour les moisissures, 2,3 % pour les levures et 14,3 % pour Escherichia coli. Tous les échantillons examinés étaient négatifs pour Salmonella spp. Les concentrations de bactéries aérobies totales n’ont pas cessé d’augmenter entre 2001 et 2004.

1Environmental Health Unit, Institute of Community and Public Health, Birzeit University, West Bank, Palestine (Correspondence to I.A. Al-Khatib:

Received: 27/09/06; accepted: 03/12/06

EMHJ, 2009, 15(3): 709-716

Introduction

Milk is a highly nutritious food that, unfortunately, is ideally suited to the growth of pathogenic organisms. Consumption of raw milk remains a well-identified risk factor for foodborne disease but pasteurization has been highly effective in ensuring the safety of dairy products [1,2]. In some countries, especially those with a warm climate, raw milk and products such as cheese continue to be responsible for many outbreaks of gastroenteritis [3]. Several outbreaks of typhoid fever in industrialized countries have been ascribed to consumption of unripened hard cheese made from raw milk handled by chronic carriers [4,5]. Some of the bacteria can cause severe illness with long-term consequences and death [6–9]. Enteric bacilli multiply in milk at ordinary atmospheric temperatures, so that even a trivial contamination may cause an explosive outbreak. Sporadic infections may, however, result if the product is contaminated during the distribution process [4]. Industrial cattle breeding and food production facilitate the spread of non-typhoidal Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp. and possibly Yersinia enterocolitica [2,10,11].

The aim of this report was to explore the microbiological quality of dairy products from different sources from Ramallah and Al-Bireh district and to assess the quality of the health inspection procedures based on the number of samples collected.

Methods

Data on the microbiological quality of dairy samples was obtained from the records of the Central Public Health Laboratory of the Palestinian Ministry of Health (MoH) for the Ramallah and Al-Bireh district. The collected data were for the years of 2001–04.

A total of 722 dairy product samples were collected randomly from different sources by environmental health inspectors of the Palestinian MoH in routine inspections over the study period. Samples were taken from raw milk, yogurt, pasteurized milk, labneh (concentrated yoghurt), salt cheese and cooked cheese. The samples were collected from different sources such as dairy factories, sweet shops, grocery shops, restaurants and vendors of various sectors encompassing the whole of Ramallah and Al-Bireh district. The samples were collected in pre-sterilized containers and transported in ice-buckets to the Palestinian Central Public Health Laboratory in Ramallah city on the day of collection.

The analyses covered total aerobic count (TAC), and the presence of total coliforms, faecal coliforms, Staphylococcus aureus, moulds, yeasts and Salmonella spp. The criteria (cut-off levels) for unacceptable contamination for each measure are shown in Table 1. Decisions regarding whether food samples were considered acceptable for human consumption were based on the microbiological guidelines for food samples of the MoH [12] that mainly depend on the Palestinian Standards Institution. The bacteriological analytical manual online, published by the United States Department of Health and Human Services [13], was used as a reference for sample testing.

The data were reviewed, cleaned and revised with the help of the Environmental Health Department personnel of the MoH as well as Central Public Health Laboratory technicians. The data were coded and analysed using SPSS, version 12.0.

Results

The total number of tested dairy samples from different sources in Ramallah and Al-Bireh district increased slightly from 2001 (n = 203) to 2002 (n = 236) but decreased to 2004 (n = 109).

Table 2 shows the annual frequency and percentage of levels of contamination in dairy product samples for the different tests conducted. From 2001 to 2004, the number of samples graded as unacceptable increased for TAC and faecal coliforms. There was no overall trend of increasing or decreasing numbers of unacceptable samples for the indicators examined. The proportion of samples with unacceptable levels of TAC increased from 2001 to 2004, while for other indicators acceptability increased or decreased over time.

A significant statistical relationship was seen between the sampling year and the number of unacceptable dairy samples, with a rising trend of unacceptable levels over time for TAC (χ2 = 52.626; P < 0.001), total coliforms (χ2 = 9.382;P = 0.025), faecal coliforms (χ2 = 18.938; P < 0.001), moulds (χ2 = 11.956; P = 0.008) and Staph. aureus (χ2 = 13.703; P = 0.003) (Table 2).

Figure 1 shows the average overall percentage of acceptable samples during 2001–04. All of the samples examined tested negative for Salmonella spp.

Discussion

Dairy products prepared under unhygienic conditions pose a great threat to the health of consumers in Palestine, who consume them in large amounts. This study in Ramallah and Al-Bireh district showed relatively high rates of dairy samples that did not meet Palestinian standards for acceptable levels of contamination.

TAC is a quality control test that is a basic measure of the bacteria in dairy products. It reveals general sanitation and herd health conditions. So the high proportion of samples with unacceptable TAC in this study (23.0%) my be a result of poor sanitation and bad herd health conditions in Ramallah and Al-Bireh district.

Coliform testing is a more specific bacteriological test for the quality of dairy products. While the presence of coliform bacteria does not necessarily signify that pathogens are present or that the produce has come in contact with faeces, high counts are an indicator of poor herd hygiene, improperly washed and maintained equipment or a contaminated water supply [14]. The existence of samples with unacceptable levels of total coliforms in this study (21.0%) was likely due to unsanitary conditions or practices during production, processing or storage of the dairy products. More concerning is the high proportion of samples with unacceptable levels of faecal coliforms (15.2%). These include E. coli O157:H7, Salmonella and Shigella [15] and are considered to be directly associated with faecal contamination from warm-blooded vertebrates [16].

Enterotoxins produced by Staph. aureus can cause food poisoning: a large-scale mass outbreak in Japan was caused by skim-milk powder contaminated with Staph. aureus enterotoxin A [17]. In our study unacceptable levels of Staph. aureus were found on average in 1.0% of samples during 2001–04 and may be attributed to the practice of preparing large batches too far in advance and holding them for long periods at room temperature. It also indicates poor hygiene conditions and faults in manufacturing/handling during cheese production.

The most common sources of food poisoning from Salmonella spp. are beef, poultry and eggs, but improperly prepared fruits, vegetables, dairy products and shellfish have also been implicated [18]. All the examined samples tested negative for Salmonella spp. in all years of the study.

While yeasts are needed to ferment and ripen many cheese varieties and make a positive contribution to the development of taste and aroma [19–23], they may also act as spoilage organisms causing yeasty off-flavour, loss of texture, excessive gas formation and increased acidity [24,25]. The average rate of samples with unacceptable levels of yeasts in this study was 2.3%.

There are several factors which may explain the high levels of dairy food contamination in Palestine: inadequate levels of health inspection, economic and transport difficulties and poor knowledge and practices among farmers.

We noted a rising trend of unacceptable TAC over the period of the study, from 8.7% in 2001 to 47.3% in 2004. Accompanying this was a fall in the total number of dairy samples tested, from 203 in 2001 to 109 in 2004. This may be a reflection of the unstable political situation in Palestine, which has led to lower standards of health inspection and difficulties in timely and hygienic transport of diary products. Dairy farmers are rarely visited by the Ministry of Health inspectors or veterinary health inspectors of the Ministry of Agriculture. Experience suggests that such visits make farmers feel responsible for the safety of milk that originates from their farms, and this will result in the reduction of the sources of microbial contamination. Most of the milk in Ramallah and Al-Bireh district is produced in the villages by farmers with small landholdings. Although an increasing proportion of the milk produced is collected by cooperatives and other organized dairies, much of the milk is still processed in traditional ways, with inadequate refrigeration and transportation facilities, especially during sieges, invasions and curfews imposed by the Israeli military forces on Palestine.

Data limitations include unsystematic testing, as not all the samples were uniformly tested for the different indicators

From field observations in our study, some of the staff handled dairy products with open sores without wearing a waterproof protection. There are also no strict regulations for the dairy plant process to be followed by the workers in this district. For example, many of them did not regularly wear work clothes that show dirt easily. In addition, many workers in places where dairy products are served, such as restaurants and school cafeterias, did not wear a head or beard cover while serving food.

The conditions under which milk is produced in the villages are also far from satisfactory, mainly because of the poor economic situation and lack of practical knowledge of proper milk hygiene measures on the part of the producers. The milk animals are housed in small closed or open yards adjacent to the family house. Flooring is usually of plaster or mud. The cows are rarely washed before milking. Milking is done by hand. Because of the distances between the production and consumption points, milk is unavoidably kept at ambient temperatures and this supports rapid microbial growth, especially during the summer. This situation is similar to that in Turkey, where most milk and dairy products are not prepared under hygienic conditions [26,27]. Our results also agree with research conducted in Karak, Jordan, where samples of unpasteurized milk, yoghurt, labnah and white soft cheese produced by farmers by traditional methods showed a high viable coliforms count (indicative of unsanitary conditions), yeasts, moulds and Staph. aureus, which indicates serious faults in production hygiene, unsatisfactory sanitation and unsuitable storage temperature [28].

There are some steps that can be taken to improve the situation. One is the development of rational schedules for microbiological testing of dairy samples to include all months of the year, especially the summer ones. Also, the development of proper sanitation and herd health conditions will help reduce the levels of contamination. Dairy farmers need to be encouraged to feel responsible for the safety of milk that originates from their farms.

Additional efforts should be made by the veterinary health services provided by the Ministry of Agriculture to ensure that dairy herds are free of any infectious diseases which could be transmitted to humans through milk or its products. Suspect animals should be isolated for treatment and their milk destroyed. Public awareness targeting dairy factories and households that produce dairy products should encourage and help them to follow strict and detailed technical and hygiene procedures in order to maintain good quality produce.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation for funding this research.

References

- Headrick ML et al. The epidemiology of raw milk-associated foodborne disease outbreaks reported in the United States, 1973 through 1992. American journal of public health, 1998, 88:1219–21.

- Ruegg PL. Practical food safety interventions for dairy production. Journal of dairy science, 2003, 86:E1–9.

- Altekruse S et al. Foodborne bacterial infections in individuals with the human immunodeficiency virus. South medical journal, 1994, 87:69–73.

- Vaishnavi C et al. Bacteriological study of Indian cheese (paneer) sold in Chandigar. Indian journal of medical microbiology, 2001, 19(4):224–6.

- Khan SA et al. Characterization of erythromycin-resistant methylase genes from multiple antibiotic resistant Staphylococcus spp. isolated from milk samples of lactating cows. American journal of veterinary research, 2000, 61:1128–32.

- D’Aoust JY. Salmonella and international trade. International journal of food microbiology, 1994, 24:1–31.

- Desenclos JC et al. Large outbreak of Salmonella enterica serotype paratyphi B infection caused by goats’ milk cheese, France: a case finding and epidemiological study. British medical journal, 1996, 312:91–4.

- O’Donnell ET. The incidence of Salmonella and Listeria in raw milk from farm bulk milk tanks in England and Wales. Journal of the Society of Dairy Technology, 1995, 48:25–9.

- Rampling A. Raw milk cheeses and salmonella. British medical journal, 1996, 312:67–8.

- Grundmann H. [Differential therapy of infectious diarrhea] Differentialtherapie von infektiosen Durchfallerkrankungen. Praxis (Bern 1994), 1994, 83:1176–8.

- White DG et al. The isolation of antibiotic-resistant salmonella from retail ground meats. New England journal of medicine, 2001, 345:1147–54.

- Microbiological guidelines for food. Ramallah, Palestine, Department of Environmental Health, Ministry of Health, 2000.

- Bacteriological analytical manual online. Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, United States Food and Drug Administration, 2001 [website] (http://vm.cfsan.fda.gov/~ebam/bam-toc.html, accessed 22 January 2009).

- Coliforms. International Specialty Supply [website] (http://www.sproutnet.com/Reports/coliforms.htm, accessed 22 January 2009).

- Eliminate fecal coliforms. University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources [website] (http://groups.ucanr.org/UC_GAPs/Elimanate_Fecal_Coliforms/, accessed 22 January 2009).

- Paille D et al. Seasonal variation in the fecal coliform population of Louisiana oysters and its relationship to microbiological quality. Journal of food protection, 1987, 50(7):545–9.

- Soejima T et al. Comparison between ultrafiltration and trichloroacetic acid precipitation method for concentration of Staphylococcus aureus enterotoxin in dairy samples. International journal of food microbiology, 2004, 93:185–94.

- Excerpt from salmonellosis. eMedicine [online article] (http://www.emedicine.com/med/byname/salmonellosis.htm, accessed 22 January 2009).

- Jakobsen M, Narvhus J. Yeasts and their possible beneficial and negative effects on the quality of dairy products. International dairy journal, 1996, 6:755–68.

- Viljoen BC, Greyling T. Yeasts associated with Cheddar and Gouda making. International journal of food microbiology, 1995, 28:79–88.

- Dea’k T et al. Molecular characterization of Yarrowia lypolytica and Candida zeylanoides isolated from poultry. Applied and environmental microbiology, 2000, 66:4340–4.

- Rossi J et al. Yeasts in dairy. Annali di microbiologia ed enzimologia, 1997, 47:169–83.

- Cosentino S et al. Yeasts associated with Sardinian ewe’s dairy products. International journal of food microbiology, 2001, 69:53–8.

- Walker SJ. Major spoilage microorganisms in milk and dairy products. International journal of dairy technology, 1988, 41:91–2.

- Fleet GH. Spoilage yeasts. Critical reviews in biotechnology, 1992, 12:1–44.

- Arslan A et al. The presence of Listeria, Salmonella, E. coli type 1 and Klebsiella pneumoniae on the ice creams sold in Elaz. Turkish journal of veterinary and animal science, 1996, 20:109–12.

- Akman D. Prevalence of Listeria species in ice creams sold in the cities of Kahramanmarafl and Adana. Turkish journal of medical sciences, 2004, 34:257–62.

- Al-Tahiri R. A comparison on microbial conditions between traditional dairy products sold in Karak and same products produced by modern dairies. Pakistan journal of nutrition, 2005, 4(5):345–8.