N.Al-Hamdan,1 K. Ravichandran,2 J. Al-Sayyad,3 J. Al-Lawati,4 Z. Khazal,5 F. Al-Khateeb,5 A. Abdulwahab 6 and A. Al-Asfour 7

معدَّل وقوع السرطان في بلدان مجلس التعاون الخليجي، 1998-2001

ناصر الحمدان، كاندا سامي رافيشاندران، جمال الصياد، جواد اللواتي، زينب خزعل، فلاح الخطيب، عبد العظيم عبد الوهاب، عادل العصفور

الخلاصـة: يصف الباحثون أنماط معدَّلات وقوع السرطان الأكثر شيوعاً في دول مجلس التعاون خلال الفتـرة 1998-2001. وقد وجدوا أن 291 32 حالة سرطان قد شُخِّصت (342 16 لدى الذكور و949 15 لدى الإناث). وقد لوحظ رجحان الذكور في المملكة العربية السعودية وسلطنة عُمان فقط، كما وجدوا أن معدَّل الوقوع المصحّح بحسب العمر لجميع أنماط الأورام الخبيثة لدى الجنسين محسوباً لكل ألف من السكان كان الأعلى في قَطَر يتلوه في البحرين والكويت وسلطنة عُمان والإمارات العربية المتحدة والمملكة العربية السعودية. كما وجدوا أن سرطانات الطفولة تـتـراوح بين 9.5% من مجموع حالات السرطان في المملكة العربية السعودية وفي الإمارات العربية المتحدة و4% في البحرين. كما وجدوا أن وسطي العمر عند التشخيص في جميع البلدان كان أعلى في الذكور منه في الإناث، وأن سرطان الرئة وسرطان البروستاتا هما الأشيع عند الذكور، وسرطان الثدي والدرق عند الإناث. ويحتل سرطان الرئة المركز الثاني لدى النساء في البحرين.

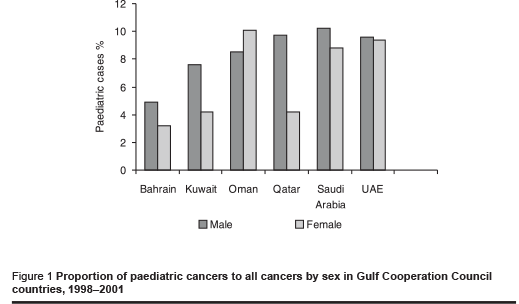

ABSTRACT We describe the patterns of cancer incidence for common cancers in Gulf Cooperation Council countries during 1998–2001. A total of 32 291 cases of cancer were diagnosed (16 342 in males; 15 949 in females). Male preponderance was observed only in Saudi Arabia and Oman. The age-standardized incidence of all malignancies per 100 000 in both sexes was highest in Qatar followed by Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, UAE and Saudi Arabia. Paediatric cancer ranged from 9.5% of total cancers in Saudi Arabia and UAE to 4.0% in Bahrain. In all countries, the mean age at diagnosis was higher in males than females; cancer of the lung and prostate were commonest among males, and cancer of breast and thyroid among females. Lung cancer ranked second among Bahraini women.

Incidence du cancer dans les pays du Conseil de coopération du Golfe, 1998–2001

RÉSUMÉ Nous décrivons les tendances de l’incidence des cancers courants dans les pays du Conseil de coopération du Golfe de 1998 à 2001. Au total, 32 291 cas de cancer ont été diagnostiqués (16 342 chez les hommes et 15 949 chez les femmes). La prépondérance masculine n’a été observée qu’en Arabie saoudite et à Oman. L’incidence normalisée en fonction de l’âge de toutes les affections ma-lignes pour 100 000 personnes chez les deux sexes était la plus élevée au Qatar, suivi de Bahreïn, du Koweït, d’Oman, des Émirats arabes unis et de l’Arabie saoudite. Les cancers pédiatriques représentaient entre 9,5 % du nombre total de cancers en Arabie saoudite et aux Émirats arabes unis et 4,0 % à Bahreïn. Dans tous les pays, l’âge moyen lors du diagnostic était plus élevé chez les hommes que chez les femmes ; les cancers les plus répandus chez les hommes étaient les cancers du poumon et de la prostate et, chez les femmes, les cancers du sein et de la thyroïde. Le cancer du poumon arrivait en deuxième position chez les femmes à Bahreïn.

1Ministry of Health, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; 3Ministry of Health, Manama, Bahrain; 4Ministry of Health, Muscat, Oman; 5Ministry of Health, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; 6Ministry of Health, Doha, Qatar; 7Ministry of Health, Kuwait (Correspondence to N. Al-Hamdan:

2Department of Biomedical Statistics and Scientific Computing, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Received: 23/05/06; accepted: 08/06/06

EMHJ, 2009, 15(3): 600-611

Introduction

Cancer is the second most frequent cause of death in the majority of developed countries and is emerging also as a major public health problem in developing countries. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) estimated that, globally, nearly 11 million new cases of cancer and more than 6 million deaths from this disease occur annually and approximately 7 million people live with cancer [1] with more than half of the cases arising in developing countries where resources for treatment and prevention are scarce. Rapid improvements in the field of health care, together with the control of communicable diseases, increased life expectancy at birth and rapid socioeconomic changes resulting in modified lifestyles (such as increased prevalence of tobacco use, decrease in physical activity and unhealthy eating habits) are believed to contribute to the increased incidence of cancer in developing countries.

Cancer registries are a unique source of information for any cancer control programme and for developing strategies for cancer health programmes. These data help in the allocation of financial and manpower resources in cost-effective healthcare planning as well as in the design of early detection and prevention programmes. They also facilitate in the detection of carcinogens and monitoring of environmental control programmes and environmental exposure to carcinogens [2].

The geographical location and similarities in culture, lifestyle and environment of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries translates into similar health risks. However, it is recognized that there are variations in cancer incidence and frequency in these countries [3–11]. Earlier studies of cancer incidence from this region are either hospital-based, reflecting referral patterns rather than true incidence, or pertain to one cancer type or country.

We present here the of cancer incidence within the 6 GCC countries, and comparisons with other countries based on National Cancer Registry (NCR) data. The relevant epidemiological factors affecting the most common cancers in this region are alsobriefly discussed. This information is useful to public health authorities, decision-makers and researchers.

Methods

The Gulf Centre for Cancer Registration (GCCR) was established to create a population-based incidence database for the GCC countries—United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Oman, Qatar and Kuwait—and started accumulating data from 1 January 1998. The main office is located at the Research Centre of King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre in Riyadh. It collates the data collected by the national cancer registry of each GCC country after performing quality assurance. Data are sent to the GCCR in different formats (e.g. Excel, Epi-Info) and at the GCCR all files are converted to CanReg format, validated software for processing cancer data developed by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), and subsequently analysed.

The NCR in each country is responsible for data collection at the national level from health facilities. To ensure comprehensive data collection, a ministerial decree in each of the GCC countries has rendered cancer a reportable disease by all Ministry of Health hospitals, and government and private hospitals, clinics and laboratories. However, the data for this study were collected by active and passive methods. They included personal identifiers and demographic information (name, age, sex, nationality, address, etc.), tumour details (date of diagnosis, basis of diagnosis, histology, topography, stage, etc.), treatment and follow-up information. The International classification of diseases for oncology was used to classify the topography and morphology of the cancers [12]. Each registry codes the data and matches patient identifiers to ensure that each case is eligible and registered only once.

Information on prevalence of smoking and reproductive factors of GCC nationals was obtained mostly from the family health surveys (FHS) conducted in all GCC countries [13–18].

The results presented in this report are based on the incidence of cancer cases diagnosed during the period 1998–2001 among nationals of GCC countries. The crude incidence rate and age-standardized incidence rate (ASR), standardized to the world standard population, were used to describe the data. The population by sex was estimated at 1 January 2000 for each country by 5-year age category. The incidence of the 5 most common cancers are shown by their relative frequency in each country and by sex.

Results

During 1998–2001 the total number of cancer cases registered among GCC nationals was 32 291 (males 16 342; females 15 949). Overall, the male:female ratio was 102:100, however, male preponderance was observed only in Saudi Arabia (104:100) and Oman (114:100). The highest frequency of cancer occurred in Saudi Arabia followed by Oman, Kuwait, Bahrain, UAE and Qatar, both in males and females (Table 1). The ASR per 100 000 of all malignancies in both sexes, was highest in Qatar (male 165.5; female 172.4), followed by Bahrain (male 157.7; female 144.6).

Cancers of the lung and prostate among males and cancers of breast and thyroid among females were the most common cancers in almost all the GCC countries (Table 1). Non-Hodgkin lymphoma ranked within the top 5 in all countries except in Bahrain and among women in Oman. Leukaemia ranked within the top 5 in all GCC countries except in Kuwait and among women in Bahrain (Table 1).

A high proportion of cancers in those aged < 15 years was observed in Saudi Arabia, UAE and Oman, at least 2-fold greater, than in Bahrain. The paediatric cancer rates were highest in Saudi Arabia and UAE (9.5%), followed by Oman (9.2%), Qatar (7.0%), Kuwait (5.7%) and Bahrain (4.0%) (Figure 1). The proportion of paediatric cancers in males was higher than in females in all GCC countries except Oman.

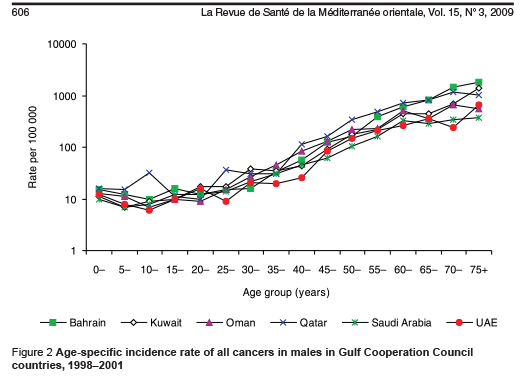

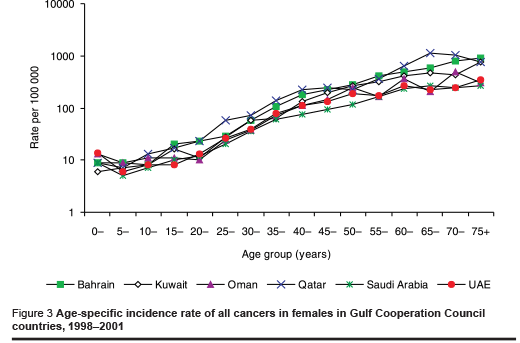

In males, the mean age when the diagnosis of cancer was made was higher in Bahrain [60.7, standard deviation (SD) 20.0 years] than Kuwait [55.1 (SD 22.5) years], Qatar [53.6 (SD 21.3) years], UAE [52.7 (SD 23.2) years], Saudi Arabia [52.6 (SD 23.6) years] and Oman [52.2 (SD 21.0) years]. For females the mean age at diagnosis was lower than males in all the countries and was highest in Bahrain [52.7 (SD 18.4) years], followed by Kuwait [50.9 (SD 18.5) years], Qatar [49.2 (SD 17.8) years], Saudi Arabia [47.3 (SD 21.0) years], Oman [46.8 (SD 20.6) years] and UAE [45.8 (SD 20.2) years]. The age-specific incidence rate of all cancers increased with age in males and females (Figures 2 and 3).

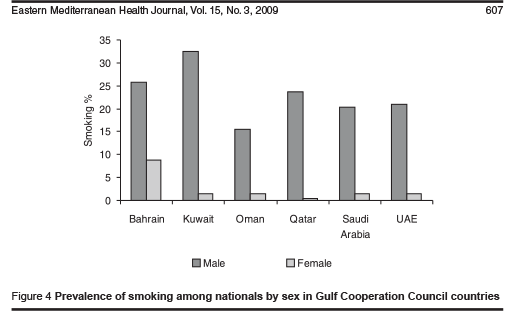

Figure 4 depicts the smoking prevalence (current smoker of any tobacco product) among males and females aged 15+ years during the mid-1990s. The highest prevalence among males was in Kuwait (32.4%), followed by Bahrain (25.8%), and Oman (15.5%) had the lowest prevalence. In females, the prevalence in Bahrain (8.8%) was ≥ 6-fold higher than in other GCC countries (ranging from 0.5% in Qatar to 1.5% in Oman and Kuwait).

Between the late 1970s and the mid 1990s the number of births per woman decreased consistently in all the GCC countries [13–24]. The duration of breastfeeding in Kuwait and Qatar was consistently lower than in other GCC countries and there was a decline in duration of breastfeeding among younger women (15–19 years) compared with older women (45–49 years) in all countries (except Qatar, data not available. Between 3% and 12% of women aged 40–44 years had their first child before the age of 15 years, compared to only around 2% of those aged 15–19 years [13–18].

Discussion

Mean age at diagnosis for cancers in the GCC was higher in males than in females and in both sexes it was about a decade younger than reported in Western populations, similar to the findings in other developing countries [2]. This could partly be explained by the younger population structure, the prevalence of existing environmental factors such as infections, poor hygiene conditions and very recent emission of carcinogens into the environment from industries. Like other developing countries, GCC countries have younger populations, with the proportion aged < 15 years ranging from 36.6% of the total population in Bahrain to 45.2% in Saudi Arabia. The high population growth, improved health care programmes and decline in infant mortality are the main contributing factors for the broad base of the population pyramid.

Comparison of the ASR of all cancers within the GCC countries shows that the incidence in Qatar was at least 2.5 times higher than Saudi Arabia for both sexes. In a similar comparison of cancer incidence in countries in 5 continents, the incidence among Qataris and Bahrainis (both males and females) was higher or equal to most of the African and Asian populations and the rate observed among Saudi Arabians was much lower than these populations [25]. The low incidence rate and higher proportion of paediatric cancers in Saudi Arabia can partly be explained by the younger population structure. Similarly, the higher incidence rate and lower proportion of these cancers in Bahrain can also be attributed to the relatively older population structure. The lower ASR may also be due to incomplete registration in the older age groups.

Lung cancer is the most common cancer in the world, comprising 12.4% of all cancers [1]. Within GCC countries lung cancer was the most common cancer in males in Bahrain, Qatar and UAE and ranked 2nd, 3rd and 4th in Kuwait, Oman and Saudi Arabia respectively. A 7-fold difference in ASR (34.3 per 100 000 population in Bahrain and 4.8 per 100 000 in Saudi Arabia) was observed among males. In females it emerged within the top 5 malignancies only in Bahrain and ranked 2nd, next to breast cancer, with an ASR of 12.1 per 100 000. Lung cancer in Bahrain accounted for one-fifth of male cancers and 6.8% of female cancers. The disease was more common in males than females in all GCC countries (74%–81% of lung cancers were among males), a finding consistent with Parkin et al. [26]. The most important risk factor for lung cancer is tobacco smoking and the supportive evidence for this association has been reviewed many times by different scientific groups and institutions [27,28]. Although the periods of collection of cancer incidence and smoking data are too short to attribute the cancer incidence to smoking practice, there has been a longer history of smoking among Bahrainis (both men and women) than in other GCC countries. Similarly, the low incidence in Saudi Arabia can also be attributed to the low prevalence of smoking. The contribution of factors such as occupational exposure to asbestos, metals and ionizing radiation may be nil or very minimal as the process of industrialization has been very recent in all GCC countries.

Breast cancer was the most common cancer among females in all the 6 GCC countries, as in most other countries [25], ranging from 15.4% of female cancers in Oman to almost one-third in Kuwait and Bahrain. Kuwait, Bahrain and Qatar can be classified as high-incidence areas and the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Oman as low-incidence areas of the GCC region. A comparison of ASR of breast cancer from the high-incidence area of GCC countries with other countries/regions around the world shows the incidence rates are about half those of the UK (high-risk area), and similar to the rates in medium-risk countries such as the Philippines and Singapore [25]. The rates for the low-incidence GCC countries were almost half those in the high-incidence countries. Most of the international and interethnic differences in incidence of breast cancer are the consequence of differing environmental exposures and lifestyles [26]. However, the differences observed within the GCC region can partly be explained by differences in the age distribution of the population (the population aged > 24 years in the high-incidence area ranges from 39%–43% in contrast to 30%–34% in the low-incidence area in addition to other risk factors such as fertility rate and duration of breastfeeding [13–18].

The traditional reproductive pattern observed in GCC countries is characterized by an early start to childbearing, short birth intervals, prolonged breastfeeding and high parity. The fertility rate in the low-incidence area was consistently higher than in the high-incidence area of GCC countries and there has been a considerable decline in all the GCC countries [13–24].

A woman’s risk for breast cancer decreases with duration of breastfeeding and with every child born [29]. The duration of breastfeeding in Kuwait and Qatar was lower than in the other GCC countries and there has been a reduction in duration in all the GCC countries along with a steady rise in the age at first childbirth. The decline in early childbearing was more rapid in the high-incidence areas. Future studies could address the gap in understanding the causes of breast cancer in this region.

The incidence of thyroid cancer shows striking differences in different age groups, sexes, ethnic backgrounds and geographical locations [25]. Thyroid cancer ranked 2nd among females in all the GCC countries except in Bahrain where it ranked 3rd. The ASR in these countries ranged from 5 per 100 000 in Saudi Arabia to 15 per 100 000 in Qatar. In males the ASR ranged from 1 to 2 per 100 000 in all GCC countries except in Qatar (4.1) and Kuwait (3.3). Worldwide, the highest incidence rates have been reported from Hawaii, Iceland, Israel and Los Angeles [25]. A comparison of ASR of thyroid cancer in the GCC countries with other countries and regions showed that the incidence rate in Qatar, especially among females, is similar to Hawaii (Filipino) where the highest incidence occurs [25]. The female preponderance of thyroid cancer is a well established fact [30]. In the GCC countries, the male:female ratio ranges from 1:5.6 in Bahrain to 1:2.7 in Kuwait. The incidence was higher among women aged < 45 years, as also observed by Young et al. [31]. Epidemiological studies have shown an association between seafood consumption and risk of thyroid cancer [32]. The study by Memon et al. from Kuwait supported the hypothesis that reproductive factors and patterns may influence, or contribute to, the risk of thyroid cancer among women [11]. Another study from Kuwait related high consumption of various seafoods to thyroid cancer [33]. There is no documented evidence of high background radiation or exposure to childhood radiation beyond medical procedures in any GCC country. Further research from the other countries should shed more light on the epidemiology of thyroid cancer in this region.

Cancer of the prostate is the third most common cancer among men in the world, accounting for 11.7% of all new male cancers, with a high incidence in Europe, North America and Australia [1]. Prostate cancer, although not a top cancer in any of the GCC countries, ranked within the top 5 malignancies in all countries and ranged from 5.2% of male cancers in Saudi Arabia to 8.7% in Oman. The highest ASR was seen in Bahrain (14.8 per 100 000). The low relative frequency in GCC countries may be related to the male population distribution, with less than 6% reaching the age of 60 years. However, the fact that this is a cancer of the elderly and about three-quarters of cases worldwide occur in men aged 65 years or more [26] was evident in our data from Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. In fact, more than four-fifths of the cases occurred in men aged 60 years or more, except in the UAE (73.7%). Even though the population structure of GCC countries is significantly different from that of the United States of America (USA), the mean age at diagnosis of prostate cancer (Bahrain 72.1 years, Saudi Arabia 71.9 years, Kuwait 71.4 years, Qatar 68.4 years, Oman 66.2 years and UAE 65.9 years) was comparable to the USA where it is 68 years [34].

Despite extensive research, the environmental risk factors for prostate cancer are not well understood [26]. A Western-type diet seems to play a role, but there is no convincing evidence implicating any particular dietary components, although some studies have suggested that consumption of fats, meat and dairy products increases the risk [35]. Despite an influx of affluence foods from developed countries over the last 3 decades in Saudi Arabia, Hanash et al. could not find any difference in the amount of fat in the diet of men with and without prostate carcinoma [36]. This may be due to factors such as the relatively small sample size, genetic and racial factors, under-diagnosis and environmental and hormonal factors. However, protective nutrients, such as a high-fibre diet, cereals, cooked tomatoes, rice, tea, fruits, vegetables, dates and dairy products are consumed in large quantities in the standard Saudi diet and may negate the deleterious effect of a high saturated fat diet. A study in Kuwait and Oman indicated that Arab men had lower prostate-specific antigen levels and prostate volumes than Caucasians. The levels are slightly lower than those reported in Japan and, as in the Japanese, low prostate-specific antigen levels and small prostate volumes might be related to the low incidence of clinical prostate cancer in Arab men [37]. Future genetic studies could further enhance knowledge about the epidemiology in the GCC region.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma was the commonest cancer in Saudi Arabia and the 2nd commonest in Oman and Kuwait among males. In females it ranked within the top 5 malignancies in all the GCC countries except Bahrain and Oman. The incidence in GCC countries is between the low European/American and high African rates. Low socioeconomic status, malnutrition and the prevalence of parasitic and viral infections are associated with lymphomas in many developing countries [38]. A higher prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in Saudi Arabian patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma was identified by Harakati et al. [7]. To our knowledge, no relationship to the Epstein–Barr virus has been confirmed so far in GCC countries. Despite the fact that this is a common malignancy in both sexes in the GCC countries, there are gaps in our knowledge about its epidemiology.

The GCC countries share a common geographic location and industrial base and as a result face similar environmental conditions. Furthermore, the similarities in culture and lifestyle resulted in somewhat similar cancer patterns in these countries. However, the magnitude of the cancers was different between the countries. Furthermore, the high incidences of cancer of the stomach among men in Oman and the UAE, and lung cancer among women in Bahrain were specific to these countries. Although the occurrence of lung cancer among Bahraini women can be attributed to tobacco smoking, the real differences in incidence of other cancers are not easy to interpret. This warrants further research to identify the risks associated with each cancer and to establish the environmental causes.

This study demonstrates the similarity in the occurrence of cancer in GCC countries and features pertaining to each country. In addition, our data show the overall lower incidence rate among GCC nationals was similar to many African and Asian populations. The incidence rate for selected cancers was equal to or higher than industrialized countries.

References

- Ferlay J et al., eds. GLOBOCAN 2002: cancer incidence, mortality and prevalence worldwide, version 2.0. Lyon, International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2004 (IARC Cancer Base No. 5).

- Greenwald P. Principles of cancer prevention: diet and nutrition. In: DeVita VT Jr, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, eds. Cancer: principles and practice of oncology. Philadelphia, JB Lippincott, 1989.

- Ghafoor M, Schuyten R, Bener A. Epidemiology of prostate cancer in United Arab Emirates. Medical journal of Malaysia, 2003, 58(5):712–6.

- Shome DK et al. Spectrum of malignant lymphomas in Bahrain. Leitmotif of a regional pattern. Saudi medical journal, 2004, 25(2):164–7.

- Qari FA. Pattern of thyroid malignancy at a University Hospital in Western Saudi Arabia. Saudi medical journal, 2004, 25(7):866–70.

- El Hag IA et al. Pattern and incidence of cancer in northern Saudi Arabia. Saudi medical journal, 2002, 23(10):1210–3.

- Harakati MS, Abualkhair OA, Al-Knawy BA. Hepatitis C virus infection in Saudi Arab patients with B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Saudi medical journal, 2000, 21(8):755–8.

- Al-Lawati JA et al. Cancer incidence in Oman, 1993–1997. Eastern Mediterranean health journal, 1999, 5(5):1030–34.

- Rasul KI et al. Study of colorectal cancer in Qatar. Saudi medical journal, 2001, 22(8):705–7.

- Makar RR, Saji T, Junaid TA. Epstein–Barr virus expression in Hodgkin’s lymphoma in Kuwait. Pathology and oncology research, 2003, 9(3):159–65.

- Memon A et al. Epidemiology of reproductive and hormonal factors in thyroid cancer: evidence from a case–control study in the Middle East. International journal of cancer, 2002, 97(1):82–9.

- International classification of diseases for oncology, 2nd ed. (ICDO-2). Geneva, World Health Organization, 1990.

- Fikri M, Farid SM. United Arab Emirates family health survey 1996. Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, Ministry of Health, 2000.

- Naseeb T, Farid SM. Bahrain family health survey 1996. Manama, Ministry of Health, 2000.

- Khoja TA, Farid SM. Saudi Arabia family health survey 1996. Riyadh, Ministry of Health, 2000.

- Sulaiman AJM, Al-Riyami A, Farid SM. Oman family health survey 1996. Muscat, Ministry of Health, 2000.

- Jaber KA, Farid SM. Qatar family health survey 1996. Doha, Ministry of Health, 2000.

- Alnesef Y, Al-Rashoud R, Farid SM. Kuwait family health survey 1996. Kuwait, Ministry of Health, 2000.

- Al Muhaideb A et al. United Arab Emirates child health survey 1987. Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, Ministry of Health, 1991.

- Yacoub I, Farid S. Bahrain child health survey 1989. Manama, Ministry of Health, 1991.

- Al Mazrou Y, Farid S. Saudi Arabia child health survey 1987. Riyadh, Ministry of Health, 1991.

- Suleiman MJ et al. Oman child health survey 1988–89. Muscat, Ministry of Health, 1992.

- Salman A et al. Qatar child health survey 1987. Doha, Ministry of Health, 1991.

- Al-Rashoud R, Farid S. Kuwait child health survey 1987. Kuwait, Ministry of Health, 1991.

- Parkin DM et al., eds. Cancer incidence in five continents. Volume VIII. Lyon, International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2002 (Scientific Publication No. 155).

- Parkin DM, Bray FI, Devesa SS. Cancer burden in the year 2000. The global picture. European journal of cancer, 2001, 37(Suppl. 8):S4–66.

- Tobacco smoking: evaluation of carcinogenic risk to humans. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risk to humans. Lyon, International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1986 (Publication No. 38).

- Smoking or health: the third report from the Royal College of Physicians of London. London, Pitman Medical, 1977.

- Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and breastfeeding: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50 02 women with breast cancer and 96 973 women without the disease. Lancet, 2002, 360:187–95.

- Fraker D. Radiation exposure and other factors that predispose to human thyroid neoplasia. Surgical clinics of North America, 1995, 75(3):365–75.

- Young J Jr, Percy C, Asire A, eds. Surveillance epidemiology and end results: incidence and mortality data (1973–1977). National Cancer Institute monographs, 1981, 57:1.

- Berg JP et al. Long-chain serum fatty acids and risk of thyroid cancer: a population-based case control study in Norway. Cancer causes and control, 1994, 5(5):433–9.

- Memon A, Varghese A, Suresh A. Benign thyroid disease and dietary factors in thyroid cancer: a case–control study in Kuwait. British journal of cancer, 2002, 86(11):1745–50.

- Miller DC et al. Prostate carcinoma presentation, diagnosis, and staging: an update from the National Cancer Data Base. Cancer, 2003, 98(6):1169–78.

- Diet, nutrition and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington DC, World Cancer Research Fund in association with American Institute for Cancer Research, 1997.

- Hanash KA et al. Prostatic carcinoma: a nutritional disease? Conflicting data from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Journal of urology, 2000, 164(5):1570–2.

- Kehinde EO et al. Age-specific reference levels of serum prostate-specific antigen and prostate volume in healthy Arab men. British journal of urology, 2005, 96(3):308–12.

- De Vita VT Jr et al., eds. Lymphocytic lymphomas. In: DeVita VT Jr, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, eds. Cancer: principles and practice of oncology. Philadelphia, JB Lippincott, 1989