Ramez Mahaini1

1Coordinator, Family and Community Health, Division of Health Protection and Promotion, WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, Cairo, Egypt (Correspondence to Ramez Mahaini: mahainir@emro. who.int).

EMHJ, 2008, 14(Supplement): S97-S106

Introduction

The fifth Millennium Development Goal (MDG) aims to improve maternal health. The 2 targets set for this goal are to “reduce by three-quarters, between 1990 and 2015, the maternal mortality ratio” and “achieve, by 2015, universal access to reproductive health”. Six indicators have been selected to help track progress towards these targets: maternal mortality ratio; proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel; contraceptive prevalence rate; adolescent birth rate; antenatal care coverage (at least 1 visit and at least 4 visits); and unmet need for family planning [1].

This paper briefly outlines the general situation in relation to maternal health in the Eastern Mediterranean Region of the World Health Organization (WHO) and goes on to focus on the perspective of adolescent pregnancy and reproductive health.

General regional and subregional trends of the goal

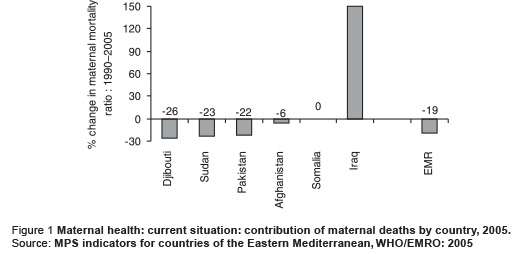

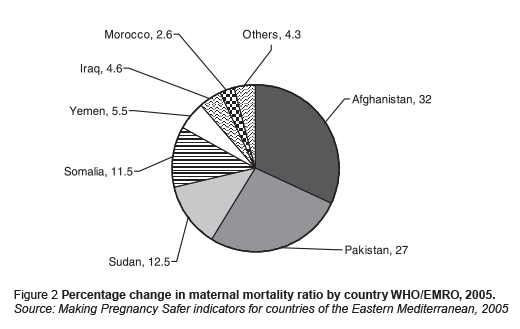

Improving maternal health has been endorsed as a key development target by Member States. It has been included in consensus documents arising from international conferences, including the World Summit for Children in 1990, the International Conference on Population and Development in 1994, the Fourth World Conference on Women in 1995, the Millennium Summit in 2000 and the United Nations General Assembly Special Session on Children in 2002 [2]. Despite the international efforts and commitment to the Safe Motherhood Initiative since its inception at the Nairobi Conference in 1987, progress towards reducing maternal mortality globally has been slow. According to the WHO/United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)/United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), global estimates on maternal mortality in 2005 indicated that 536 000 women continue to die every year as a result of pregnancy-related complications [3]; around 53 000 of these women die in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region [4]. Over 95% of the burden of maternal death in the Region is shared by 7 countries, namely Afghanistan, Iraq, Morocco, Pakistan, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen (Figure 1) [4].

In 2005, the mean maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in the Eastern Mediterranean Region was estimated at 377 per 100 000 live births, compared to 465 per 100 000 live births in 1990, a reduction of only 18.9% in maternal death in the Region in the period from 1990 to 2005. If the current trend in reducing maternal death continues in the years to come, MMR is expected to be around 300 per 100 000 live births in the year 2015, while the target for MMR set by the MDG in the Region is 116 per 100 000 live births (75% lower than its level in 1990) (Table 1) [4].

It is worth mentioning here that the reduction in MMR has not yet exceeded 30% in 6 countries in the Region (Figure 2). These are: Afghanistan, Djibouti, Iraq, Pakistan, Somalia and Sudan. These countries contribute to over 90% of maternal deaths in the Region (Figure 1) [4].

However, there are great variations in maternal death levels among countries of the Region, ranging from 0 in Bahrain to 1600 per 100 000 live births in Afghanistan and Somalia (Table 1). In other words, countries of the Region can be classified in the 4 following groups.

- MMR is less than 100 per 100 000 live births: this group contains 14 countries, namely: Bahrain, Egypt, Islamic Republic of Iran, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia and United Arab Emirates.

- MMR ranges from 200 to 400 per 100 000 live births: this group contains Morocco, Iraq, Pakistan and Yemen.

- MMR ranges from 500 to 600 per 100 000 live births: this group contains Sudan and Djibouti.

- MMR is around 1600 per 100 000 live births: this group contains Afghanistan and Somalia.

Regional trends of teenage marriage and pregnancy in relation to the MDG5

Adolescent pregnancy is commonplace in many countries. An estimated 14 million women aged from 15 to 19 years give birth each year to around 10% of all births worldwide. More than 90% (12.8 millions) of these female adolescents live in developing countries [5]. More than half the women in sub-Saharan Africa and about a third in Latin America and the Caribbean give birth before the age of 20 years [6]. The regional average rate of births per 1000 women aged 15–19 years is 143 in sub-Saharan Africa and 78 in Latin America and the Caribbean compared to the world average of 65 [7]. Meanwhile, in the 28 countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the percentage of women who give birth before age 20 years ranges from 2% in Japan to 13% in the United Kingdom and 22% in the United States [8].

For example, in the Arab world families are experiencing major changes as new patterns of marriage and family formation emerge across the Region. Universal early marriage is no longer the standard it once was in Arab countries [9] (Table 2). The average age at marriage for both men and women is generally rising, and more Arab women are staying single longer or not marrying at all. While these trends are part of a general global phenomenon, they are also introducing new issues into Arab societies, issues that can confront deeplyrooted cultural values and present legal and policy challenges. Changing demographic patterns of marriage in the Arab world reflect broader social and economic changes taking place throughout the Region. Arab economies have increasingly moved away from an agrarian system, which supported both early marriage and an extended family structure [9] (Table 3).

Situation analysis of youth reproductive health in the Region

WHO, in its contribution to meeting the MDGs, is according priority attention to issues pertaining to the management of adolescent pregnancy. Three of the aims of the MDGs, the empowerment of women, the promotion of maternal health and the reduction of child mortality, embody key priorities of WHO and its overarching policy framework of poverty reduction. The UN Special Session on Children in particular focused on some of the key rights issues affecting adolescents, including early marriage, access to sexual and reproductive health services, and care for pregnant adolescents.

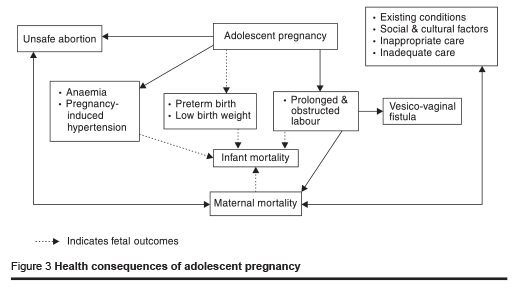

Adolescent girls face considerable health risks during pregnancy and childbirth, accounting for 15% of the Global Burden of Disease for maternal conditions and 13% of all maternal death [10]. Adolescents aged 15–19 years are twice as likely to die during childbirth and those under age 15 are 5 times as likely to die during childbirth as women in their twenties [8]. Unsafe abortion (defined by WHO as a procedure for terminating unwanted pregnancy either by persons lacking the necessary skills or in an environment lacking minimal medical standards or both), pregnancy-induced hypertensive diseases [11] and severe anaemia [12] contribute to a large extent to high maternal mortality among adolescents (Figure 3). Infant and child mortality is also higher among children born to adolescent mothers [13].

Adolescents suffer a significant and disproportionate share of death and disability from unsafe abortion practices [14]. The number of abortions globally among adolescents ranges from 2.2 to 4 million annually [15]. Recent estimates reveal that 14% of all unsafe abortions in developing countries are performed on adolescents aged 15–19 years. Of these unsafe abortions in developing countries, Africa accounts for 25% while Latin America and the Caribbean account for 14% [16].

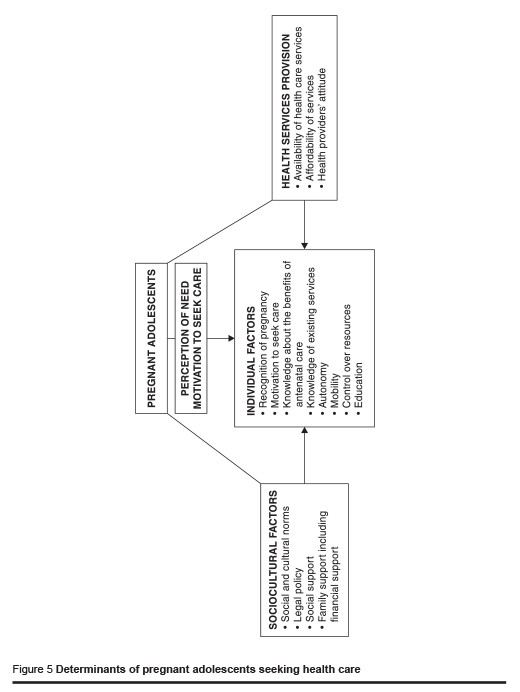

Pregnant adolescents vary greatly in their circumstances, their behaviour and consequently their needs. Lack of information about the needs of pregnant adolescents means that service providers are ill equipped to deal with them. Failure on the part of communities to acknowledge and address the issues related to and stemming from the problem further complicates the situation. There are major barriers that preclude adolescents’ access to maternal health care services. Failure to address these barriers and needs seriously threatens the healthy outcomes of the young mother and newborn child and further contribute to the already high maternal mortality ratio and pregnancy-related morbidities.

A major challenge to adequately meeting the educational, informational and clinical needs of adolescent women in developing nations is the eradication of existing social and cultural biases against adolescent women. Youth-friendly services are reported among the best strategies to overcome such a challenge. Therefore, the needs of pregnant adolescents must be approached from a holistic standpoint, rather than a solely biomedical perspective (Figure 3).

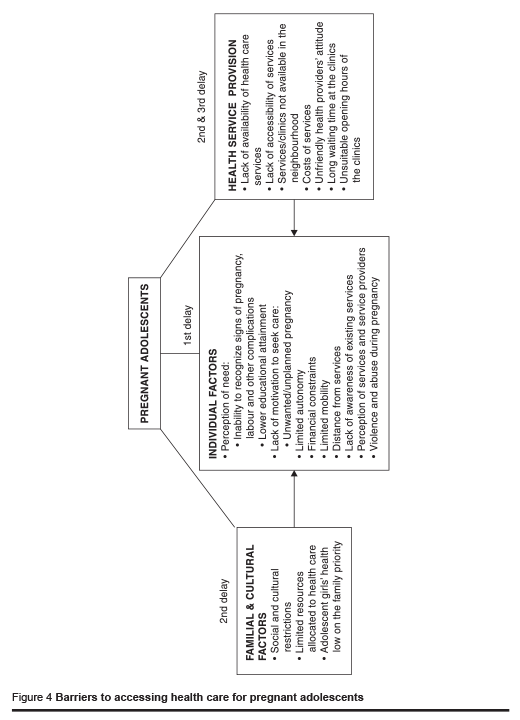

There are 3 generally identified delays in accessing and receiving care that contribute to maternal and infant mortality [17] (Figure 4):

- Delay in deciding to seek care on the part of the individual, family or both. Factors that shape the decision to seek care include actors involved in decision-making (individual, partner, family, community); this also includes knowledge about pregnancy, labour and symptoms and signs of complications (perception of need), status of women, costs, and cultural factors.

- Delay in reaching an adequate health care facility. Causes include an inability to access health facilities because of underdeveloped transportation infrastructures, nonexistent communications networks, prohibitive costs of transportation and other financial constraints.

- Delay in receiving adequate care at an existing facility. Causes include inefficient triage systems, inadequate caregiver skills, inadequate numbers of caregivers, inadequate equipment and supplies and lack of a referral system.

Although these delays are largely systemic, and thus affect health care for most pregnant women in developing countries, their presence poses particular challenges for the care of pregnant adolescents because of an adolescent’s physical and psychological immaturity and limited autonomy. Unless appropriate actions to eliminate these delays and evidence-based practices and procedures are implemented, it will be unrealistic to reduce maternal mortality ratios, especially among adolescents (Figure 5).

Policy recommendations pertaining to overall and youthspecific attainment of MDG5 at the regional level with a focus on gender issues and concerns

The evidence cautions that the situation of pregnant adolescents varies tremendously by age, marital status, whether the pregnancy is wanted or unwanted, social class, educational attainment, urban or rural residence, region and cultural context; this therefore calls for interventions that are flexible and responsive to these disparate needs. Policies must address the underlying social, cultural and economic factors that contribute to pregnancy and childbearing among adolescents. They must improve the status of adolescent girls and expand their opportunities through the following actions.

- Opportunities for formal education should be provided and reproductive health education introduced into the curricula at school. Special efforts are needed to overcome barriers that preclude young girls from attending school. Greater political commitment and resources are required to improve the overall status of girls.

- Pregnant and parenting girls need to be able to continue their schooling. Traditionally, pregnant schoolgirls have been forced to leave school. Policies designed to keep girls in school will allow them to acquire education and develop skills that will enhance their ability to care for themselves and their families, and to take advantage of worthwhile employment opportunities.

- Existing laws on minimum age of marriage should be publicized and enforced towards establishing statutory marriage law applicable to all marriages. Experience in many countries suggests that it is difficult for policy-makers to influence age at marriage and childbearing directly. In spite of the legal age limit at marriage being 16 or 18 years, many women marry before reaching this age.

- Reproductive health information and youth-friendly services for married and unmarried, non-pregnant and pregnant adolescents should be legally available and widely accessible.

- Health providers should be trained particularly in counselling and interpersonal communication skills to better work with adolescents. Adolescents should particularly be given adequate social support during pregnancy, labour, delivery and postpartum period.

- Safe motherhood programmes need to be particularly vigilant, sensitive and responsive to physical abuse of adolescents during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

- Maternal health care for adolescents should be provided early and include pregnancy test, counselling, early detection and management of complications, psychological support, and nutritional, iron and vitamin supplementation. Treatment and management of malaria and other communicable diseases in endemic areas should be a component of antenatal care provided to adolescents.

- In light of the higher incidence of premature delivery in adolescents, planning for the birth should be undertaken, including the place of birth, availability of transportation and costs involved.

- Postpartum care should be provided as it is particularly important for adolescents in order to promote and support breastfeeding and provide the contraceptive method of choice.

- Individuals, families and communities, including social and religious leaders and other key decision-makers, should be targeted to increase their knowledge on the health and social burden associated with adolescent pregnancy. This intervention should help ensure provision of the required support to pregnant adolescents.

References

- United Nations Population Fund. About the Millennium Development Goals (http:// www.unfpa.org/icpd/about.htm, accessed 7 July 2008).

- Making Pregnancy Safer: WHO’s flagship programme to improve the lives of women and their newborns. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2003.

- Maternal mortality in 2005: estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2007 (http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/ publications/maternal_mortality_2005/, accessed 7 July 2008).

- MPS indicators for countries of the Eastern Mediterranean. Cairo, WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 2005 (http://www.emro.who.int/rhrn/statistics.htm, accessed 7 July 2008).

- World Population Monitoring 2002 – reproductive rights and reproductive health: selected aspects. New York, United Nations, 2004 (ST/ESA/SER.A/215).

- Into a new world: young women’s sexual and reproductive lives. New York, Alan Guttmacher Institute, 1998.

- The progress of nations 1998. New York, United Nations Children’s Fund, 1998.

- A league table of teenage births on rich nations. Florence, UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre, 2001 (Innocenti Report Cards, No. 3).

- Rashad H, Osman M, Roudi-Fahimi F. Marriage in the Arab world. Washington DC, Population Reference Bureau, 2005.

- World Health Organization, Global Programme on Evidence, 2000.

- Granja A et al. Adolescent maternal mortality in Mozambique. Journal of adolescent health, 2001, 28:303–6.

- Brabin B, Hakimi N, Pelletier D. An analysis of anemia and pregnancy related maternal mortality. Journal of nutrition, 2001, 131:604S–614S.

- World Population Profile: 1996. Washington DC, US Bureau of the Census, 1996.

- Singh S. Adolescent childbearing in developing countries: a global review. Studies in family planning, 1998, 29:117–36.

- Olukoya A et al. Unsafe abortion in adolescents. International journal of gynecology and obstetrics, 2001, 75:137–47.

- Shah I, Ahman E. Age patterns of unsafe abortion in developing country regions. Reproductive health matters, 2004, 12(Suppl.):9–17.

- Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: Maternal mortality in context. Social science & medicine, 1994, 38:1091–110.