Ahmed Ali Abdullatif1

1World Health Organization Representative Egypt and Former Coordinator, Health Systems Development, Division of Health Systems and Services Development, World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, Cairo, Egypt (Correspondence to Ahmed Ali Abdullatif:

EMHJ, 2008, 14(Supplement): S23-S41

Introduction

In celebrating the 30th anniversary of primary health care (PHC) and the declaration of Alma Ata in 1978, it is useful to remind ourselves that PHC was identified as the means or strategy to achieve health for all. In other words PHC was considered a comprehensive health developmental approach. Such an approach includes several features and each word in the phrase “primary health care approach” represents an essential constituent.

Thus the “Primary” element means that it involves what is essential from the perspective of burden of disease, epidemiology, morbidity, mortality and cost–effectiveness, as well as what is acceptable. The “Health” element means complete health as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), i.e. a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. Health is also seen in the context of overall development and encompasses the social determinants of health. Related sectors and the community usually contribute more to the “H” of PHC than the Ministry of Health which focuses on services or rather the PC of PHC. The “Care” element (which is broader than cure) includes preventative, curative and rehabilitation-related care. It also covers personal and public aspects. The “Approach” element indicates that PHC is dynamic, health system-oriented and is the means to achieve health for all. As the health system orientation covers health services and nonhealth services, such as nutrition, water and sanitation, primary care (PC) is sometimes used interchangeably with PHC. There is, however, a clear difference. PC can be considered the essential or basic service provided by the health authorities and is the most widely addressed component of PHC as a whole worldwide. PC provides promotive (mainly health education), preventive and curative care.

PHC values and principles

PHC is a global public health movement based on ethical values and principles. Despite the faltering implementation of the PHC approach, the world has come to see that its values and principles are time-tested and as much needed now as they were in 1978. The principles of PHC include: equity, universal coverage, involvement of the people, comprehensiveness, integration, human rights based, person/user centredness.

A value to people-centred care and the protection of the health of communities requires a response that only PHC-based health systems can provide.

Equity is a fundamental principle of PHC and is congruent with the vision of health for all. It incorporates social inclusion and intolerance of health inequality. Health is thus a human right.

The PHC approach encompasses social values that put people in the driving seat; health systems are driven to respond to what people need and aspire to. Such peoplecentred health care delivery requires a health system where:

- close-to-client health care networks exist which allow individual, family and community problems to be seen in context;

- providers and people can build enduring relations of trust that are necessary for care to be comprehensive, integrated, continuous and appropriate;

- people have and know their rights, have choices, and can participate in decisions affecting their health;

- health strategies are comprehensive and integrated with overall development. Intersectoral action and community involvement are essential requirements to ensure comprehensiveness, self-reliance and sustainability of all activities related to PHC.

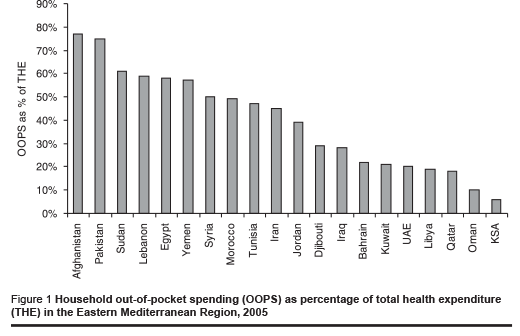

An important PHC principle relates to the way we think of and work for health development. PHC is about thinking deeper and addressing root causes – the determinants of health. A consistent theme throughout the PHC approach has been the need to change the way we think about health and healthcare. The existing systems are inherently reactive organizations, designed primarily to cope with poor health, to pick us up when we fall. They are not designed to reduce the likelihood of poor health. Furthermore, PHC considers health a strategic element of overall development. Recent economic studies have shown how people can be impoverished because of ill health and catastrophic expenditures (Figure 1).

Another principle of PHC is value for money. Within this context, primary care is about provision of essential care, which is most cost-effective. In comparison with specialized care, primary care is associated with a more equitable distribution of health care in the populations of countries which have opted to base their national health systems on PHC.

Findings and lessons learnt in EMR

The voice of the developing world was loud and clear at Alma Ata in support of PHC and most Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR) countries accepted and have benefited from the PHC approach. PHC also paved the way for other related initiatives, such as poverty alleviation and the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which EMR countries also subscribed to and have benefitted from.

All of our countries, rich or poor, are living in two worlds, one for the well off and powerful and one for everyone else. The two worlds are on divergent paths and this is not ethical or acceptable.

The health in the Region has improved and continues to do so but more slowly than aimed for (Table 1). Life expectancy and proximity to health services have continued to increase overall, but large parts of the Region have been left behind.

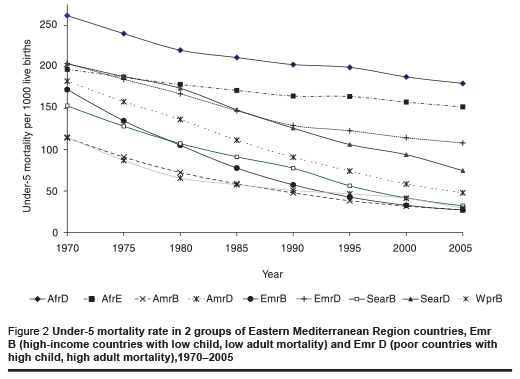

Assessment of PHC in EMR indicates that perhaps the main achievements have been in the P and C components of PHC. But even this has been with a variable degrees of success both between countries and, more importantly, within countries. Using MDG number 4 (under-5 mortality) as a proxy overall indicator, progress is slower than would reasonably be expected (Figure 2), and very variable. High-income countries in EMR with low child, low adult mortality (EMR B countries) have already achieved MDG 4, whereas poor countries with high child, high adult mortality (EMR D countries) are lagging behind. Furthermore, the gap between the 2 country groups has widened since 1970 (Figure 2).

Progress has not only been uneven in child health. Indicators show that while some countries are on track to meet the health for all goals, others are not keeping up, are stagnating, or are even going into reverse. Table 2 shows the stark inequalities among EMR countries with reference to some selected indicators.

As well as wide between-country gaps, exclusion of certain groups and withincountry inequalities are evident and have had direct and indirect effects on health. For example, Table 3 shows that Egyptians had, on average, 3.5 outpatient visits per year. In comparison with other lowand middleincome countries, Egyptians are above average users of outpatient services. However, utilization rates vary significantly by region and income. Individuals in urban areas had 4.48 outpatient visits per year compared to 2.75 visits in rural areas. Outpatient visit rates varied with income level. Individuals in the highest income quintile (annual per capita income > 1700 Egyptian pounds) had the highest number of visits (5.11 visits), compared with those in the lowest income quintile (annual per capita income < 560 Egyptian pounds) with 2.32 visits. For outpatient care the richest had over twice as many visits as the poorest, an indicator of inequity in access to care. The situation in most EMR countries likely follows a similar pattern of inequalities.

At the policy level, health leaders in EMR are learning from experience. The dominant pattern of thought in the EMR has assumed that what is required is either more of the same (more hospitals, nurses, doctors, technology) or delivering the same things in a different way (service redesign, community-based care). There is now a general recognition of the need for a comprehensive approach to health development to ensure better performing health systems. There is therefore a greater readiness to take a fresh look at the potential of PHC and its track record in circumstances where it received adequate support. The evidence shows that, in today’s globalized world, adherence to PHC values is the solution to meet what citizens expect for themselves and their families, and what they aspire for their society.

The achievements by countries that adhered to PHC principles and strategies, such as Oman, where infant mortality rate was reduced from 118 per 1000 live births in 1970 to 10.25 per 1000 live births in 2008 and the under-5 mortality rate was similarly reduced from 181 per 1000 live births in 1970 to 11 per 1000 live births in 2008, and the Islamic Republic of Iran, where the neonatal mortality rate was reduced from 71 per 1000 live births in1970 to 21 per 1000 live births in 2000 and the mortality rate in children aged 1–59 months was reduced from 150 per 1000 live births in 1970 to 14 per 1000 live births in 2000, prove the merits of the PHC approach. When there is the will, PHC flourishes.

The State has the ultimate responsibility for organizing health systems around the values that drive PHC. Stronger leadership is needed to guide the Ministry of Health in adopting a new role and new style of working. This redefinition of roles is important in all countries but particularly urgent in low-income countries. Experiences indicate the need to strengthen the role of the Ministry of Health and government and their capabilities in 3 key areas: i) explicit and effective mechanisms for inclusiveness and engagement with a variety of stakeholders; ii) information and knowledge management which includes continuous, real-time evaluation as well as projections of future health challenges; and iii) capacity of the leadership to combine long-term vision, alliancebuilding and strategic policy dialogue with national and international stakeholders.

The quality of primary care varies from one country to another in EMR and tends to follows the same pattern as the service indicators. Several quality initiatives are under way but are still in their early phases, especially in middle-income countries.

Making use of the experiences in developed countries in gatekeeping and efficient use of resources, several countries have embarked on the family physician model; it is expected that about 80% of ailments can be dealt with at this level.

Recently some countries have revisited the provision of care especially 2 main aspects: economic and organizational. Introducing prepayment schemes, such as health insurance schemes, forced national health authorities to consider an economically feasible package which will allow reallocation of scarce resources to essential care (Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen and Iraq). Wealthy countries have also considered a wider package to prepare citizens for a defined package as well as to introduce the gatekeeper concept (Bahrain, Oman, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait). Some lower income countries have also considered packages for improving quality of care (Tunis, Egypt) and providing feasibility and sustainability. Needless to say, these packages, while they mimic primary care’s essential care by incorporating preventive, promotive and curative care, fall short because they are facility-based and reactive rather than proactive; nor do they address the determinants of ill heath. This is not to underestimate the achievements of such schemes but rather to qualify what needs to be developed further on the unfinished agenda of PHC in the 21st century.

Challenges and the unfinished agenda of PHC in EMR

One may wonder why we did not obtain better results with PHC. The following challenges explain shortfalls in performance and response of the health sector in most EMR countries.

Alienation of the health workforce

Differences in professional culture and financial disincentives explain why health care providers have been reluctant to integrate population-based interventions and health care services. In particular a major challenge is integrating population-based work in the practice of private providers.

Fragmentation of care

Political and managerial responsibilities (and the corresponding financing mechanisms) for population-based services are located in different institutions or different branches of government from those dealing with people-centred care. Because of this situation, efforts to decentralize did not work and also there was little input from the people themselves in the decision-making for their health and well-being.

Shrinking role of MOH as a normative national institution

The global and national policy environments (structural adjustment, decentralization of the entire public sector, poverty reduction strategies, trade policies, new tax regimes, fiscal policies, withdrawal of the State) have not been sensitive to health issues. Health authorities have failed to anticipate or assess the health impact of these changes. They have shown a poor track record in influencing these policies and have been unable to use the economic weight of the health sector for leverage.

Disrupted health systems

In some EMR countries, war and humanitarian crises (Afghanistan, Iraq, Palestine, Somalia, Sudan) have damaged health and impeded health progress, both directly and by disruption of health systems.

Erosion of trust in the performance of national health systems

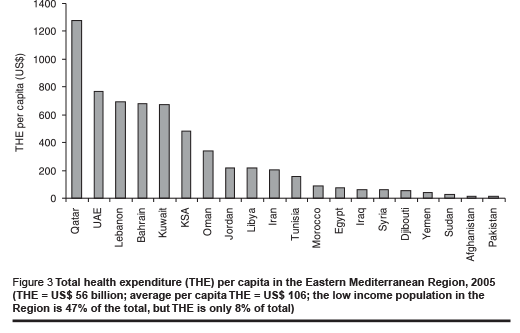

There has been chronic under-funding of national health systems, as shown in Figure 3. This has led to under-investment in the infrastructure and human resources for health, which thus has limited the scale of response to people’s needs. There has also been an erosion of trust in the system among the people as a result of wrong choices in investing in health where the share of primary care expenditure in most countries is modest in absolute and relative terms. The health systems of developing countries are thus trapped in a vicious circle of loss of trust and under-performance. Striking examples are high household out-of-pocket expenditure, especially in lowand middleincome countries (Figure 1) and expenditure on treatment abroad. For example, in Yemen it is estimated that a third of total health expenditure is for treatment out of the country.

Capacity to cope with change

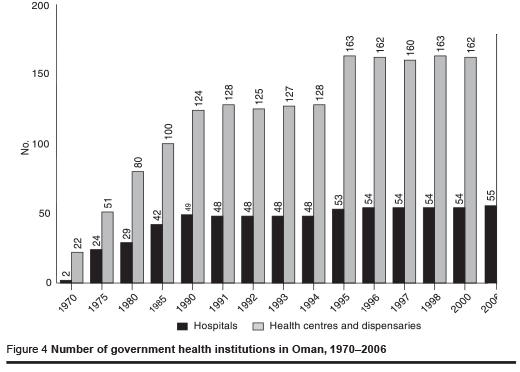

Policy choices within the health sector have not kept pace with the challenges of the health transition, both old and new, including the diseases of poverty, ageing, urbanization and globalization. In addition, the potential of prevention and promotion has been undervalued. Figure 4 shows how Oman has invested judiciously in primary care centres rather than hospitals since 1975. This correct investment policy is also seen in the developed countries, such as the United Kingdom, where primary care is the default health system and the number of hospital beds has steadily decreased since 1928.

Policy dilemma

Tools, methods and working systems used for policy choices within the health sector have also not kept pace with the demands that have come with globalization, modernization and the amount of information available. The nature of (at times supplyinduced) demand is changing. Unlike the market, health leaders have been slow in taking this into account and devising and using new economic, societal, managerial and quality tools.

Dilemma of organization of care in a globalized world

It has been a challenge to know how best to respond to different forms of trade agreements, patents rights and technology transfer. In national health systems that are traditionally fragile and have not been able to cope adequately with healthcare delivery, it is uncertain if they can cope with the additional more complex politico-economic environment of today and the future.

Conflicting messages from international donors and partners History should not repeat itself by sending conflicting messages on revitalization of PHC as happened soon after the Alma Ata conference. An effective safety measure against this is to help national health authorities take the lead in steering national health programmes and the international support they may receive when revitalizing PHC.

Regional aspirations, our strategic axes for action

Bearing in mind all the above discussion, there is a need to outline the strategic axes to be taken in the next decades to revitalize the PHC approach in EMR.

Despite the deepening economic crisis and increase in food prices globally, the climate for health is not unfavourable for the following reasons.

- The world is better armed now to maximize the impact of PHC for health and health equity both technologically because of new technology and information networks, and also socially because of growing civil society involvement in health and the collective global thinking and solidarity for health.

- The awareness of the link between health and poverty makes it possible to establish alliances beyond the health sector. It shows that the responsibility of health leaders is not just for survival and combating diseases, but for health as a capability in society.

- Global health is receiving unprecedented attention, with growing interest in integrated action and comprehensive and universal care.

EMR countries should therefore seize the opportunities to advance health and “market” PHC values and principles. For example, it is possible for developing countries within the EMR to make substantial gains in reducing the infant mortality rate, as has been done in some countries of the Region, in a shorter period of time than that taken by developed countries in the past: in the United Arab Emirates, the time taken to reduce infant mortality from 100 per 1000 live births to 30 per 1000 live births was 12 years (1965–77); for Oman the time was 15 years (1975–90), for Kuwait 25 years (1955–80), while in England and Wales it was 36 years (1915–51) (Hill & Yazbeck, 1994; Mitchell, 1988).

In pursuit of the ultimate strategic goal of health for all, the following axes are proposed.

Balancing accountability for health, health care, wellness and illness

The fact that many health problems have multiple determinants makes it necessary for PHC population-based interventions to rely on multisectoral approaches, which are challenging to establish and sustain. Furthermore, illness care is only one part if health and PHC should develop to be a vehicle for health promotion, protection and disease control, its core constituents. To maximise these aspects, it is necessary i) for the State to take measures to ensure that population-wide health protection (e.g. iodine supplementation, road safety, etc.) is funded and implemented; and ii) to ensure that, where appropriate, such protection is fully integrated with the development of people-centred services.

Much more proactive leadership is needed by the State. It needs to: i) survey the current social, political and economic background, to build consensus and explain how PHC can respond to the complex combination of challenges, opportunities and aspirations, and to provide communities and other stakeholders with examples of actions they can take now, and in the mediumand long-term, to achieve greater progress in health of the people; ii) improve access by scaling up PHC networks, through strategies that are tailored to the different contexts and circumstances; iii) use financial leverage to improve equity, in particular through targeted strategies to reach the unreached, especially those in the lowest percentiles; (iv) implement initiatives such as institutional development of local government and decentralization; (vi) establish the basic structures of accountability within the PHC system. These make effective links between the first level (such as health centres), the districts, and ultimately the Ministry of Health.

Strengthening needs assessment and responsiveness

One of the core principles of PHC is that health care should be organized and delivered in response to needs in the communities served. The implication of this principle is that the PHC system must have the capacity to assess need in order to change services and improve outcomes.

The capacity to assess need becomes more important when the health system is facing major epidemiological and demographic change (which is the case in developed and developing countries). At present, the capacity for needs assessment in the PHC system in the EMR is limited and needs to be improved, particularly at the district and health facility levels. This requires redeployment of significant resources to the districts, in order for them to build the capacity for needs assessment.

Making strategic investment decisions in support of PHC infrastructure

Primary care is about provision of essential care which is most cost-effective. The evidence from EMR countries shows that primary care in comparison with specialized care is associated with a more equitable distribution of health care in populations of countries who opted to base their national health systems on PHC. Delivering basic services in primary care requires careful and skillful planning and multiples levels of support – basic is not simple! Strategic investment planning of this sort is arguably the clearest demonstration of any health system’s commitment to PHC. An example of appropriate investment in primary care is provided by Oman (Figure 4).

The traditional approach to budget setting in health systems will often work against the implementation of a robust model of PHC. For example, as demand from an ageing population results in increased pressure on hospital beds, the temptation is to invest in hospital capacity in response. This would be a traditional and reactive planning model. The alternative is to anticipate those changes well in advance, and to invest in improvements to the PHC infrastructure and reduce the need for hospitalization.

In addition to financial investment in PHC, certain policies are needed in relation to:

- Guaranteeing universal access to essential care through an adequate health system preferably supported by a social security system;

- Ensuring a shift from vertical diseaseoriented programmes towards a horizontal community-oriented approach;

- Organizing health systems in an intersectoral network, with cross links to environment, economy, work and education at different institutional levels;

- Using the bottom-up approach involving civil society. The basic development needs approach (BDN) in EMR is a time-tested approach that can be used in different socioeconomic settings, particularly the deprived ones.

Shifting resources to match different communities’ needs

The future orientation of the PHC system needs to be towards identifying changing needs in diverse communities, and deploying resources in response to those needs. This will make the PHC system more flexible and responsive at the local level. The differences in communities can be seen in age profile, economic status, morbidity patterns, degrees of rurality and also care utilization. Thus each community is different and unique.

The PHC system initially followed a strategy of standardization. However, as needs within communities become more diverse, resources will need to be redirected among communities to deliver a better local match of need and capacity. Ensuring the most effective match should be one of the most important functions of the districts and provinces in the future. This argument also addresses the equity principle. Stratification of communities according to their needs requires close communication with and indepth knowledge of the community being served. Databases and indicators, such as demographic and health surveys, are thus necessary tools to help achieve this and track progress.

Harmonizing the divide between personal and communal care Population-based approaches when adopted have to be rooted in a strong primary care delivery network, even where personal health care delivery does not include the prevention and promotion programmes (as in commercial health care provision).

The stratification of the population according to the spectrum of their health conditions is one method to strike the balance between personal and communal care. At one end of the spectrum is the healthy population whose needs are for promotion and counselling and equipping them with skills to sustain their healthy status. At the other end of the spectrum is the disabled population with mental or disabling conditions whose particular needs are for rehabilitation and hospice care. In between are those who are at risk, those suffering from acute diseases and those suffering from different grades of chronic disease. Stratification should include everyone and ensure that at any stage of one’s life essential healthcare needs are met. The number of strata must be limited to enable national PHC systems to offer a sensible array of integrated services for each stratum and to make these care services available almost everywhere.

This axis is essential for building the credibility of PHC. There is a very large burden of death and suffering from communicable and noncommunicable diseases. Much of this burden could be averted by improved capabilities for their prevention and treatment at the primary care level. Treating tuberculosis is personal care but is also communal care, whereas treating diabetes is personal care. Nonetheless, curbing the magnitude of diabetes in the long term is a communal issue requiring a comprehensive public strategy to address the lifestyle patterns of the community. Future efforts to advance PHC should emphasize “comprehensive” PHC that addresses such problems and, more generally, addresses emergency and other unforeseeable situations which fall more within the personal domain.

In a world threatened by emerging diseases and pandemics, vigilance of PHC is needed. Any pandemic, such as avian influenza, exposes weak areas in the national health care system, not just in individual care but more importantly in communal care, and not just in standard areas, such as childhood immunization, but more in resources allocation and decision-making. When building PHC capacity, it is resilience and experience that will protect both individuals and the community and will hold a system together during a crisis, rather than large-scale financial and infrastructure investment alone.

Rethinking the boundaries of primary care

Based on the arguments above, primary care should have different first points of contact in response to different needs. With the change in burden of disease and need for continuity of care, primary care has to qualify the first level of contact to meet this. These changing patterns require interventions at more than one level of care and, in some countries, by other than the public sector alone. Chronic diseases in particular have different first contact points with the health care delivery system depending on the stage of disease, whether diagnostic, elective or emergency management, or follow-up.

The orientation of the primary care system is to deliver care locally wherever possible, and to combine health care with health protection and health promotion in the community. This can, over time, change the orientation and role of some specialties, which are traditionally seen as a part of secondary care, for example paediatrics and obstetrics. In some highly developed health systems, e.g. Oman, these specialties are part of the primary care model, with the specialists operating as members of an extended primary care team at the local level, rather than working predominantly in secondary care settings providing reactive health care.

There are growing examples worldwide of new models of care that are rethinking the boundaries of primary care. Some countries are addressing broader health and strategic thinking for healthy nations. They are looking to redirect the healthcare system from providing mainly acute and reactive care towards a model which can handle promotion and prevention more effectively.

Promoting and practising the integration of healthcare

Promoting integration involves taking a whole system perspective and actively encouraging ways of working that blur some of the distinctions between primary, secondary and tertiary care, and link them effectively. There is growing evidence from other systems that suggests that high levels of such integration can produce good results for the population, especially for chronic diseases (Green, 2005). Some practical examples include:

- Promoting co-location and co-working. This can mean encouraging specialists from secondary care to do some of their work in primary care settings, such as health centres, where they operate alongside their primary care colleagues. This has major advantages in developing the skill base within primary care and can help to develop new areas of special interest in the primary care team. It also improves accessibility for patients.

- Developing care pathways for specified patient journeys. The pathway will describe the required interventions and contributions to be made by actors, e.g. clinicians in each part of the health system for that particular patient journey, including social care, after-care and rehabilitation. The pathway therefore integrates all of the components of the whole care system and clarifies individual responsibilities. The process of developing a new care pathway also gives an ideal opportunity for modifying those contributions and improving effectiveness. In line with care pathways, it is also necessary to find a balance between interventions at different levels of care across the disease continuum so as to ensure that the health system includes health promotion, illness prevention, care of the sick and true community development. This thus redefines the comprehensiveness of services beyond those considered medically necessary. In the context of health pathways, preventing health problems and responding to them if and when they occur requires a continuum of actions at home, in community settings (e.g. places of study, play, work and worship) and in first level and referral levels of health facilities. A range of actors have roles to play in each of these settings, including patients themselves, individuals in daily contact with them (parents and other family members), as well as individuals in regular or occasional contact with them (friends, family friends, teachers, sports coaches, religious leaders and health workers).

- Using technology to link clinicians across primary, secondary and tertiary care. The most obvious example is telemedicine, which allows clinicians in primary care settings to have direct access to the skills of their specialist colleagues, in real time, and in relation to particular patients. This promotes co-consulting, and can avoid substantial travelling for the patient. In addition, such technology can help reach isolated and dispersed populations.

- Devolving more tasks to the primary care level. New healthcare issues and needs have arisen, such as emerging diseases, healthy living for ageing, debilitating chronic conditions, socially deprivation and injury disability. The question will always be how to strengthen primary care to be able to respond and manage such new health needs. Through devolution, provinces should have the capacity to address integration as a long-term strategy and to support activities, such as the development of new care pathways. This step will also address the present strongly oriented vertical programming.

Putting the health workforce at the centre

Within the context of comprehensive PHC, health workers have key roles to play in promoting health, preventing health problems and responding to them if and when they arise. They have roles to play both as service providers and as agents of change. As service providers, health workers help well individuals stay well and ill persons to get back to good health. As community change agents, health workers can help influential community members take health seriously. They need to use their credibility and influence to help educators, religious leaders, political leaders and others understand the health needs of the community and the importance of working together to meet these needs.

Health security, occupational hazards and potential devastating threats, such as avian influenza, demand that primary health care workers play a key role at the front line of epidemic detection and response.

In order to retain health workers and ensure their equitable distribution, particularly among disadvantaged areas, requires policies and strategies. Globally countries and development partners should address the issues in a more fundamental way and support for incentives for national health workers should be in the context of equity and sustainability.

Additionally, unfinished issues related to the health work force should be addressed, such as skills mix, career development, training, distribution, retention and allocation of health workers, job descriptions, and salaries and incentives.

Strengthening the steering role of national health authorities and building alliances

In its steering role, the State should support the PHC approach through strategic thinking, coordination, standards setting and quality assurance, and overall assessment of the health of the nation. The leadership of national health authorities for PHC needs to structure and organize an inclusive social debate and clearer set of relationships with key stakeholders. It should identify these stakeholders and show how establishing dialogue and relationships is a long-term endeavour, but one that conditions the successful reorientation of the health sector. With the understanding of the fundamental PHC values and principles of equity and social justice, there is a rising tide of expectation and mounting public pressure on politicians and other leaders in many countries to re-examine and redefine their commitment to such values and to demonstrate more inspired leadership.

At present, the main orientation is to the management and delivery of health services. As a result, attention at all levels is focused on health delivery activities, such as number of attendances at health centres and other measures of the “inputs” of health care. This is understandable when the concern is to ensure that all populations have access to health services through the national PHC system. For the future, however, the orientation towards accountability needs to increasingly reflect a concern for health outcomes. This will include linking social determinants of health and intersectoral action to address the root causes of health and ill health.

Alliances should have a purpose in line with PHC principles especially when scaling up access to PHC and introducing PHC in areas of massive deprivation, neglected rural areas and post-conflict situations. The State should lead by capitalizing on district health care approaches and bringing disease-based efforts together in a comprehensive and coordinated way to strengthen delivery capacity of health systems.

The vital alliance is with the community. The principle of community participation is at the heart of the Alma Ata declaration and allows people’s priorities to be considered within the health system, thus increasing their participation and inclusion. It also provides opportunities for expanding delivery of some of the key health interventions. It offers currently the most potential for realigning health care with or integrating it in overall development.

Another area for alliance with the community is financial protection as part of the safety net in addtion to empowering the excluded, e.g. the peri-urban poor.

An important asset for alliance at the national level is the public–private mix for PHC. In most settings, a wide array of healthcare providers are approached by the people to meet their primary health needs. Evidence from tobacco control in some parts of the industrial private sector in Egypt and tuberculosis programmes shows that public–private mix is a feasible and costeffective approach to engage diverse care providers so as to support health promotion, strengthen service delivery, improve access to health care and provide financial protection to the poor (WHO/EMR, unpublished data, 2008).

Developing and using new tools PHC as an approach has to be innovative and dynamic. Additional tools should be continuously developed and used to address new challenges and changes. The tools generated should cater for the following areas.

- results-based accountability frameworks to lay out what can be done to make information instrumental to improving outcomes, not only for healthcare, but also for social outcomes, such as the extent to which the system is peoplecentred, equitable and encourages participation;

- needs assessment and stratification to ensure equity, especially in the marginalized and deprived areas. In EMR due to the increasing number of displaced people and victims of civil strife, new ways of addressing the needs of such vulnerable groups have to be sought. In these settings models should also be developed to enable primary care to “navigate” patients towards emergency medical service.

- partnership of public and private sectors including division of tasks of provision and financing of care, contractual arrangements and policy setting.

- globalization and its effect at national and local levels, including magnitude of treatment taken abroad and the migration of human resources.

- role of PHC in health security especially against pandemics and newly emerging diseases.

- policy dialogue and engagement including evidence-based interventions for policy formulation, and managerial, operational and technical activities.

- promotion of self care for all the population to avoid risk factors and, for patients, to encourage compliance with treatment.

- cost–effectiveness of the PHC approach to prove its relevance and ability to address current health needs.

- effective decentralization and integration in organizing healthcare and its programmes;

- retention, recruitment and career development of human resources to ensure equity;

- effective intersectoral action;

- the best practices of participation of people and civil society organizations;

- the strategic use of evidence-based information and communication technologies to advance effective PHC;

- health financing in support of PHC and use of financial leverage to promote equity;

- effectiveness and distribution of foreign aid in sustaining PHC activities at the national level.

Training, followed by continued support and supervision of health professionals, is key to make these tools effective in revitalizing PHC.

Promoting global solidarity

If we want to move quickly on the above axes we must correct the large financing gap. Hence international solidarity is needed, organized so as to bring structural improvement to the way countries deal with health inequalities. This has implications for reshaping and focusing development aid for health.

The predicament of aid-dependent countries shows how countries can build their capacity to put pressure on the global aid environment to bring it more in line with the Paris principles of harmonization and alignment. In this regard the PHC strategy can help countries bring more coherence to global solidarity for health.

Concluding key messages

“If the determinants of health, as revealed through the PHC approach, are multiple and interactive, then policy-making must have these qualities. We need government machinery which is capable of comprehending the whole system, as a system, rather than its constituent parts…” (Harris & Hastings, 2006). In addition to its complexity, health has also become a substantial global economic activity amounting to trillions of dollars. This fact justifies much greater investment in health services research and development and building the capacity of the national health sector to understand and influence the global policies that affect progress towards PHC. It is thus of paramount importance to engage senior health sector leadership with other sectors, political leaders and key sector stakeholders in order to:

- heighten the profile of health as a political imperative and social goal;

- articulate the values that drive PHC and relate them to other sociopolitical priorities;

- develop a long-term view of the place of PHC and the whole of the health sector (and not merely its public sector components) in society;

- govern human resources for health with a double objective of re-orienting the system towards PHC and managing the human resources crisis.

Calls for real global solidarity

Poverty is not an ISSUE for the purpose of health campaigns, it is the CAUSE that should lead our lives of public service.

“Global Funds are like stars in the sky, you can see them, appreciate their abundance…..but fail to touch them”. Ministry of Health official, Malawi.

Patent rights or patient rights. The choice is clear.

PHC has demonstrated effectiveness and greater efficiency, drives equity, and has better outcomes and responsiveness in countries where it has been adopted. Thus there is a strong rationale for investing in PHC, and, given the way the world stands today and the challenges of the future, revitalization of PHC is more necessary and relevant than ever if we are to achieve the most noble and equitable of goals – health for all.

Bibliography

- Abramson W. Partnerships between the public sector and NGOs: contracting for primary health care services – A State of the Practice Paper. Bethesda, PHR Resource Center, Abt Associates, 1999.

- Bennett S, Mills A. Government capacity to contract: health sector experience and lessons. Public administration and development, 1998, 18(4):307–26.

- De Silva S. Community-based contracting: a review of stakeholder experience. Washington DC, World Bank, 2000.

- Declaration of Alma Ata. International conference on primary health care, AlmaAta, USSR, 6–12 September 1978. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1978.

- Egypt household health utilization and expenditure survey. Cairo, Ministry of Health and Population & El-Zanaty Associates, 1995

- European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. Glossary. Copenhagen, World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, 2004.

- Formulating strategies for Health for All by the year 2000. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1979 (Health for All Series, No. 2).

- From Alma Ata to the year 2000: reflections at the midpoint. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1988.

- Green A. Unpublished report, 2005.

- Harris A, Hastings N. Working the system: creating a state of well-being. Edinburgh, Scottish Council Foundation, 2006.

- Hart E, Bond M. Action research for health and social care. Buckingham, Open University Press, 1995.

- High level forum on the health MDGs. Summary of discussions and agreed action points. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2004 (http://www.who.int/ hdp/en/summary.pdf, accessed 23 July 2004).

- Hill K, Yazbeck A. Trends in under-five mortality, 1960–90: estimates for 84 developing countries. Washington DC, World Bank, 1994.

- Human rights, health and poverty reduction strategies. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2005. (Heath and Human Rights Publications Series Issue 5).

- Laverack B. Health promotion and practice: power and empowerment. London, Sage Publications, 2004.

- Loevnisohn B. Practical issues in contracting for primary health care delivery: lessons from two large projects in Bangladesh. Washington DC, World Bank, 2002.

- Martinez J. Assessing quality outcomes and performance management. In: Ferrinho P, Dal Poz M, eds. Towards a global health workforce strategy. Geneva, World Health Organization. 2003 (Studies in Health Services Organisation and Policy, 21).

- Mills A. Experiences of contracting: an overview of the literature. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1998 (Macroeconomics, Health and Development Series, No. 33).

- Mitchell BR. British historical statistics. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1988.

- Paris declaration on aid effectiveness ownership, harmonisation, alignment, results and mutual accountability. 2005 (http://www.gc21.de/ibt/alumni/ibt/docs/ Paris_Declaration_en.pdf, accessed 30 August 2008).

- Report of the Consultation on Improving Clinical Nursing Practice, Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran, 27–30 June 1994. Alexandria, WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 1994 (WHO-EM/ NUR/303/E/L).

- Report of the first regional meeting for focal points of paramedical resources development Cairo, Egypt 8–11 June 1996. Cairo, WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 1996.

- Report of the WHO Commission Macroeconomics and Health. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2002 (A55/5).

- Report on the Expert Group Meeting on Reform of Health Professions Education in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, 31 March–2 April 2002. Cairo, WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 2002 (unpublished document WHO-EM/ HRH/591/E/R).

- Rifkin SB, Pridmore P. Partners in planning: information, participation and empowerment. London, Macmillan and TALC, 2001.

- Role of academia and professional associations in support of HFA. A paper submitted to the WHO/EMR Regional Committee, 44th session, October 1997. Cairo, WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 1997

- Ruster J, Yamamoto C, Rogo K. Franchising in health: emerging models, experiences, and challenges in primary care. Washington DC, World Bank, 2003 (Public policy for the private sector, 263).

- Shadpour K. Primary health care networks in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Eastern Mediterranean health journal, 2006, 4:822–5.

- Sheaff R, Uyod A. From competition to cooperation: service agreements in primary care. A handbook for professionals and managers. Manchester, National Primary Care Research and Development Centre, University of Manchester, 1999.

- Sultanate of Oman second primary health care review mission, 18–24 March 2006. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2006.

- The work of WHO in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Annual report of the Regional Director. World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 1995 to 2006 (http://www. emro.who.int/rd/AnnualReports.htm, accessed 23 July 2008).

- Third report on regional evaluation of health for all strategies Cairo, WHO Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 1997 (unpublished document EM/RC44/9).

- Tomorrow’s doctors. Recommendations on undergraduate medical education. London, General Medical Council, 1993.

- Towards high performing health systems. Paris, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2004.

- United Nations. Universal declaration of human rights, Preamble 1948 (http://www. un.org/Overview/rights.html, accessed 23 July 2008).

- World development report 2004: Making services work for poor people. Washington DC, World Bank, 2003.

- World Health Assembly. WHA Resolution 42.38. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1989.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean, 1994. The need for national planning for nursing and midwifery in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Resolution EM/RC41/R.10.

- World health report 2003 – shaping the future. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2003.

- World health statistics 2007. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2007.