M. Rezaeian1

نسب الانتحار والقتل في بلدان إقليم شرق المتوسط

محسن رضائيان

الخلاصـة: قام الباحث بتحليل معدَّلات الانتحار والقتل في بلدان إقليم شرق المتوسط باستخدام معطيات العبء العالمي للأمراض لعام 2000. وتمَّ حساب نِسَب الانتحار إلى القتل مصنفة بحسب العمر، والجنس، ومستوى دخل البلدان، بتقسيم معدَّل الانتحار على مجموع معدَّلَيْ الانتحار والقتل. وقد مثـَّل الذكور النسبة الكبرى من ضحايا القتل، في حين مثـَّلت الإناث النسبة الكبرى من ضحايا الانتحار. وقد بلغت نسبة الانتحار إلى القتل 50% أو أقل، في جميع الفئات العمرية للذكور باستثناء الذكور في سن الستين فما فوق في البلدان المرتفعة الدخل، في حين كانت نسبة الانتحار إلى القتل في جميع الفئات العمرية للإناث أعلى من 50%، باستثناء النساء في سن الستين فما فوق في البلدان المرتفعة الدخل، وفي الإناث اللواتي تـتـراوح أعمارهن بين 5 و14 عاماً، في البلدان المنخفضة والمتوسطة الدخل.

ABSTRACT: An analysis of suicide and homicide rates was made for countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region using global burden of disease data for 2000. The suicide/homicide ratio by age, sex and country level of income was calculated by dividing the suicide rate by the sum of the suicide and homicide rate. Males were more often victims of homicide whilst females were more often victims of suicide. For all male age groups except males 60+ years in high-income countries, the suicide/homicide ratio was 50% or less while for all female age groups except those 60+ years in high-income countries and females 5–14 years old in low- and middle-income countries, the suicide/homicide ratio was over 50%.

Rapports entre suicides et homicides dans les pays de la Région de la Méditerranée orientale

RÉSUMÉ: Une analyse des taux de suicides et d’homicides a été réalisée dans les pays de la Région de la Méditerranée orientale sur la base des données relatives à la charge mondiale de morbidité pour 2000. Le taux de suicides par rapport aux homicides par âge, sexe et niveau de revenus du pays a été calculé en divisant le taux de suicides par la somme des taux de suicides et d’homicides. Les hommes étaient plus souvent victimes d’homicide alors que les femmes étaient plus souvent victimes de suicide. Pour tous les groupes d’âge des individus de sexe masculin, à l’exception des hommes âgés de 60 ans et plus dans les pays à revenus élevés, le rapport entre les suicides et les homicides était de 50 % ou inférieur, alors que pour tous les groupes d’âge des individus de sexe féminin, à l’exception des femmes âgées de 60 ans et plus dans les pays à revenus élevés et des filles âgées de 5 à 14 ans dans les pays à revenus moyens et faibles, le rapport suicides/homicides était supérieur à 50 %.

1Department of Social Medicine, Rafsanjan Medical School, Rafsanjan, Islamic Republic of Iran (Correspondence to M. Rezaeian:

Received: 12/03/06; accepted: 23/07/06

EMHJ, 2008, 14(6):1459-1465

Introduction

Suicide and homicide are both violent forms of death, albeit with a clear difference: the latter directs violence outward towards others while the former directs it inward towards oneself [1,2]. The human costs of both suicide and homicide are severe and they are compelling public health and legal issues in any country [1]. There are studies in which these violent acts are considered under the same theoretical and practical framework, i.e. as 2 alternatives in a single stream, which is referred to as the stream analogy [1–7]. However, most of these studies have been carried out on data from Western Europe/North America or non-Muslim countries. Since culture and religion could play an important role in the pattern of violent death, it is important to study the issue in the context of the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR) of the World Health Organization (WHO).

The aim of this analysis was to investigate the suicide and homicide rate within the countries of the EMR under one framework, taking into account the level of income in each country.

Methods

The present analysis used data from the WHO global burden of disease project for 2000 [8]. The aggregated results for WHO regions were published in the World report on violence and health [9]. The estimated data for suicides and homicides were based on the International classification of diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) codes E950–E959 (suicide) and E960–E969 (homicide) [10].

In the year 2000, the EMR consisted of 22 countries, which the global burden of disease project divided into 2 income levels, based on 1996 estimates of per capita gross national product (GNP). High-income countries, with a per capita GNP of US$ 9636 or more, were Cyprus, Kuwait, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. Low- and middle-income countries, with a per capita GNP of US$ 9635 or less, included the rest of the countries within EMR [9].

The estimated rates for suicidal and homicidal deaths were documented by sex and age group (5–14, 15–29, 30–44, 45–59 and 60+ years). Then the suicide/homicide ratio within each age and sex group was calculated by dividing the suicide rate by the sum of the suicide and homicide rate [1,4]: (suicide rate)/(suicide rate + homicide rate) × 100.

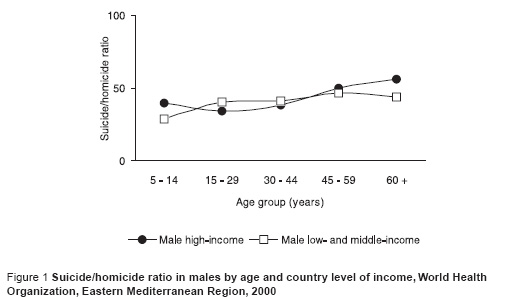

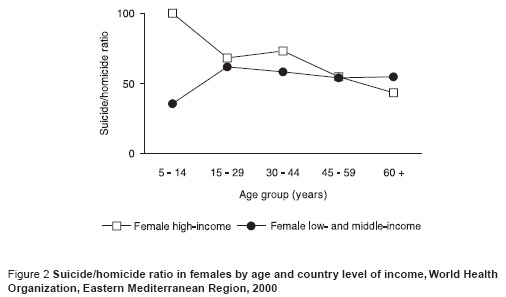

This ratio measures the proportion in which lethal violence will be expressed either as homicide or suicide. A lower suicide/homicide ratio reflects that lethal violence will be expressed as homicide and a higher ratio reflects that lethal violence will be manifested as suicide [1,4]. Suicide/homicide ratios were plotted by sex and age group and countries’ level of income.

Results

Table 1 shows suicide and homicide rates per 100 000 population and the suicide/homicide ratio in the EMR countries by sex, age group and level of income of the country. Suicide and homicide rates were higher in all age and sex groups within low- and middle-income countries in comparison with high-income countries. Furthermore, except for the age groups 5–14 and 15–29 years for suicide and age group 5–14 years for homicides, females in low- and middle-income countries had the highest rates, in all other age groups, males in low- and middle-income countries had the highest rates both for suicide and homicide.

Investigating the suicide/homicide ratio in males by age group and countries’ level of income revealed that in all age groups, except males aged 60+ years in high-income countries, the ratio was 50% or less. The highest ratio was for males 60+ years in high-income countries (56.2%) and the lowest ratio was for males 5–14 years old in low- and middle-income countries (28.6%) (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Investigating the suicide/homicide ratio in females by age group and country level of income revealed that in all age groups, except females 60+ years in high-income countries and females 5–14 years old in low- and middle-income countries, the ratio was over 50%. The highest ratio was for females 5–14 years old in high-income countries (100.0%) and the lowest in females 5–14 years old in low- and middle-income countries (35.7%) (Table 1 and Figure 2).

Discussion

In studying suicide and homicide under one stream there are 2 important issues. The first, forces of production, seeks for social and cultural factors that determine the extent of the total lethal violence. The second, forces of direction, seeks structural and cultural factors that determine the proportion of the total lethal violence manifested either as suicide or as homicide [1,2]. Under this stream, if a factor causes external blame it will increase the likelihood that the suicide/homicide ratio is expressed as homicide and vice versa.

Batton, in her longitudinal study of nationwide homicide and suicide data in the United States of America, showed that rates of alcohol consumption, immigration, and divorce were related to external attribution of blame that resulted in a higher tendency for violence to be expressed as homicide [5]. We can speculate that factors such as mental illness, political unrest, oppression and organized political violence could explain higher homicide rates among males in the EMR. A study conducted in Karachi, Pakistan revealed that homicide victims were usually males aged 20–40 years, and were also much more likely to be politically active than matched controls [11].

What factors could lead to higher suicide rates among females? It has been shown that one of the strongest risk factors for suicide is mental disorder [12,13], especially depression [14]. A recent study revealed that the prevalence of major depressive episodes in the year 2000 for the EMR was higher than the world average, estimated as 1872 and 2748 per 100 000 males and females respectively [15]. Furthermore, evidence suggests that in some countries within the EMR, married women experienced higher rates of suicide and deliberate self-harm in comparison to both married men and single women [16,17]. Again, to what extent these and other factors, e.g. women’s empowerment, illiteracy, oppression and secondary role in a patriarchal society, could explain these manifestations of higher suicide rates among females remains to be investigated.

Moreover, there are other unique cultural patterns of suicide and homicide within the Region which could to be examined. One issue is that of honour crimes, i.e. homicides committed against females by one of their male family members because the women had dishonoured the reputation of their family; these may be registered as suicides. A review of all court files of women murdered during 1995 in Jordan has shown that out of 89 homicide cases reviewed, 38 involved female victims [18]. A more in-depth study within the same country also revealed that the majority of these crimes were committed by the victim’s brother [19].

One weakness of our analysis is that only aggregated data for the whole Region were available from the global burden of disease data and it would be more informative if data were analysed by country. Other studies within the Region have shown that the rates of suicide vary from one country to another. For instance, the suicide rate within Kuwait is close to zero i.e. 0.1 per 100 000 [20], while in Saudi Arabia it is 1.1 per 100 000 [21], in Jordan 2.1 per 100 000 [22] and in the Islamic Republic of Iran 6 per 100 000 [23].

Another problem is underreporting of suicides. Although a number of people, including family members, police, doctors and coroners, are involved in recording a death as suicide, it is be possible that, for social, cultural and religious reasons, people in this Region are reluctant to report death as a suicide. Therefore, the possibility of underestimation of suicide rates should be considered [8,9,24].

More in-depth studies are needed in order to understand the factors influencing patterns of suicide/homicide in the Region, for instance the role of variables such as unemployment, migration, alcohol consumption and divorce. Migration from rural areas to suburban slums around large cities in the EMR has been linked to mental health problems, exacerbating existing problems of poverty, illiteracy and unemployment [25] and there is some evidence of increasing alcohol use among young people in some countries [26,27], counteracting the generally low level of alcohol use within the Region.

Another area for future research is the role of religious beliefs in homicide/suicide rates. Islam is the religion of about 90% of the people living in the countries of the EMR [25] and there are verses in the Koran which specifically condemn acts of suicide and homicide [26]. Therefore we might expect that the rate of such deaths in the EMR would be lower than the figures for all WHO Member States. As the statistics show, this is true as far as suicide is concerned. For instance, in the year 2000 suicide was estimated to be the 25th leading cause of death in the EMR while it was estimated to be the 13th cause of death in all WHO Member States [9]. In the same year homicide was the 21st leading cause of death in the EMR while it was the 22nd cause of death in all WHO Member States [9].

An important task is to develop national violence and injury surveillance systems with precise and reliable data on different forms of violence and their contributing factors in order to facilitate more in-depth research and analysis of homicide and suicide trends in the EMR [24,28].

Acknowledgements

The author appreciates the valuable comments of Ian Enzer and an anonymous referee on the earlier draft of this article.

References

- Wu B. Testing the stream analogy for lethal violence: a macro study of suicide and homicide. Western criminology review, 2003, 4(3):215–25.

- He N et al. Forces of production and direction a test of an expanded model of suicide and homicide. Homicide studies, 2003, 7:36–57.

- Unnithan NP, Whitt HP. Inequality, economic development and lethal violence: a cross-national analysis of suicide and homicide. International journal of comparative sociology, 1992, 33:182–95.

- Unnithan NP et al. The currents of lethal violence: an integrated model of suicide and homicide. Albany, New York, State University of New York Press, 1994.

- Batton C. The stream analogy: a historical study of lethal violence rates from the perspective of the integrated homicide-suicide model [dissertation]. Nashville, Tennessee, Vanderbilt University, 1999.

- Baller RD et al. Structural covariates of US county homicide rates: incorporating spatial effects. Criminology, 2001, 39(3):561–90.

- Wu B. Testing three competing hypotheses for explaining lethal violence. Violence and victims, 2004, 19(4):399–411.

- Murray CJL et al. The Global Burden of Disease 2000 project: aims, methods and data sources. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2001 (GPE Discussion Paper, No. 36).

- World report on violence and health. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2002 WHO/EHA/SPI.POA.2).

- International classification of disease and related health problems, ninth revision (ICD–9). Geneva, World Health Organization, 1978.

- Mian A et al. Vulnerability to homicide in Karachi: political activity as a risk factor. International journal of epidemiology, 2002, 31:581–5.

- Amos T, Appleby L. Suicide and deliberate self-harm. In: Appleby L, et al. Postgraduate psychiatry: clinical and scientific foundations. London, Arnold, 2001:347–57.

- Harris EC, Barraclough B. Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders. British journal of psychiatry, 1997, 170:205–28.

- Roy AL. Suicide. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, eds. Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry, 7th ed. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2000:2031–40.

- Ustün TB et al. Global burden of depressive disorder in the year 2000. British journal of psychiatry, 2004, 184:386–92.

- Khan MM, Reza H. Gender differences in nonfatal suicidal behaviour in Pakistan: significance of sociocultural factors. Suicide and life-threatening behavior, 1998, 28:62–8.

- Khan MM, Reza H. The pattern of suicide in Pakistan. Crisis, 2000, 21:31–5.

- Kulwicki AD. The practice of honor crimes: a glimpse of domestic violence in the Arab world. Issues in mental health nursing, 2002, 2:77–87.

- Hadidi M, Kulwicki A, Jahshan H. A review of 16 cases of honour killings in Jordan in 1995. International journal of legal medicine, 2001, 114:357–9.

- Bertolote JM. Fleischmann A. A global perspective in the epidemiology of suicide. Suicidologi, 2002, 7:6–8.

- Elfawal MA. Cultural influence on the incidence and choice of method of suicide in Saudi Arabia. American journal of forensic medicine and pathology, 1999, 20:163–8.

- Daradkeh TK. Suicide in Jordan 1980–1985. Acta psychiatrica scandinavica, 1989, 79:241–4.

- Nagavi M, Akbari M. [Epidemiology of injuries within the Islamic Republic of Iran]. Tehran, Fekrat Publications, 2001 [in Farsi].

- Rezaeian M. Age and sex suicide rates in the Eastern Mediterranean Region based on global burden of disease estimates for 2000. Eastern Mediterranean health journal, 2007, 13(4):953–60.

- Mohit A. Mental health in the Eastern Mediterranean Region of the World Health Organization with a view of the future trends. Eastern Mediterranean health journal, 2001, 7(3):353–62.

- Baasher TA. Islam and mental health. Eastern Mediterranean health journal, 2001, 7:372–6.

- A summary of Global Status Report on Alcohol. Geneva, World Health Organisation, 2001 (WHO/NCD/MSD/2001.2).

- Milestones of a global campaign for violence prevention 2005. Changing the face of violence prevention. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2005.