Aamir Jafarey1

SUMMARY Little is known about the public’s perceptions about the process of obtaining informed consent for participation in medical research. A study was made of the views of patients, their attendants, parents, schoolteachers and office workers living in Karachi, Pakistan. Participants felt that informed consent was an important step in recruiting research participants but many felt that it was a trust-based process not requiring proper documentation. For recruiting women, both men and women believed it was important to approach women through their husbands and fathers. When there was a conflict with the opinions of family leaders, it was clear that the male participants’ opinion was valued more than that of the female participants by both men and women.

Consentement éclairé : points de vue de Karachi

RÉSUMÉ On connaît mal les perceptions du public concernant le processus d’obtention du consentement éclairé pour la participation à la recherche médicale. Une étude a été réalisée sur les opinions des patients, de leurs soignants, des parents, des enseignants et des employés de bureau travaillant à Karachi (Pakistan). Les participants pensaient que le consentement éclairé était une démarche importante dans le recrutement des participants à la recherche mais nombre d’entre eux pensaient qu’il s’agissait d’un processus fondé sur la confiance qui ne nécessite pas de documentation en bonne et due forme. Pour le recrutement des femmes, les hommes et les femmes pensaient qu’il était important de contacter les femmes par l’intermédiaire des maris et des pères. Lorsqu’il y avait un conflit avec les opinions des chefs de famille, il était évident que les hommes et les femmes faisaient plus grand cas de l’opinion des participants hommes que de celle des participants femmes.

1Assistant Professor, Centre of Biomedical Ethics and Culture, Sindh Institute of Urology and Transplantation, Karachi, Pakistan (Correspondence to Aamir Jafarey:

EMHJ, 2006, 12(Supplement 1): 50-55

Introduction

As a general surgeon working at a university hospital in Karachi, Pakistan, I conduct outpatient clinics where I perform minor surgical procedures such as circumcisions. Assisting me in these clinics are junior residents from the Family Medicine Programme who are expected to learn not only minor surgical procedures but also the skills of communication with patients and families, especially while obtaining informed consent.

I recall one particular occasion when a mother brought her child to be circumcized. As usual, I started by explaining the procedure to the mother, telling her what I was going to do and what she was to expect afterwards and how to take care of the baby. After having done that I turned around to ask my resident to present the informed consent form to the mother to sign and document her permission, but the resident was nowhere to be found. A moment later the resident appeared from outside the room. “Where were you?” I enquired. “Getting the informed consent” he said, proudly displaying the signed consent form. “And how did you get this consent?” I asked. His response was prompt: “I asked the child’s father who is standing outside, to sign here” and he pointed towards the dotted line which now bore a most authoritative signature. And that was the informed consent—a signature on the dotted line. This process of getting the informed consent did not seem to upset the father, the resident, the mother or the nurse. I was the only person troubled by events as they had unfolded that afternoon.

Attitudes to a large extent dictate practice and our practice of obtaining informed consent may also largely be a result of our attitudes towards this concept of obtaining permission and who holds the authority to give permission.

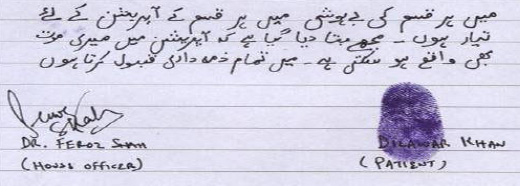

As an intern at a government hospital in Karachi in the late 1980s, I was accustomed to tearing a page out of a notebook and scribbling in Urdu “I hereby give my permission for any type of surgery to be performed on me under any type of anaesthesia. I have been told that in the course of the operation I may also die. I take full responsibility for the operation.” (Figure 1). The patient or attendant would affix a thumb-print at the bottom of the page and the intern would sign his name and that was the end of the process. This, sadly, is the practice even today in that hospital and in many other hospitals across Pakistan.

Consent documentations is just one aspect of the whole issue of obtaining informed consent and even in Karachi there are great variations in the practices that are followed. These range from basic forms that provide no information to the patient, up to elaborate International Standards Organization (ISO)-certified forms in both English and Urdu. However, even in the latter case, the common practice is that the patient signs on the English side even though the great majority of conversations with patients take place in Urdu. Another observation is that most people just listen and sign the form without any attempt to read what is written. They seem to trust their physician. This appears to have shaped the clinical practice and the attitudes of the physicians.

A study of patients’ perceptions about informed consent

Perceptions on what patients or the general public expect regarding the process of informed consent are generally based on either anecdotal evidence gathered from the patients or from information collected from physicians and researchers [1,2]. Little is known about the public’s perceptions about the process of obtaining informed consent for participation in medical research. A study was therefore designed to find out directly from the people living in Karachi their perceptions about the process of informed consent for participation in medical research and for participation in health care decisions for therapy. This was an exploratory study, intended to point the way towards further studies in this area.

The relationship between a patient and a physician is considered essentially a trust-based relationship with the sole motive of the physician being the benefit to this patient. Research is different from therapy; the goals of the researcher are much broader and the participant is a means towards a greater objective and may or may not benefit from the interaction. There were two arms to the study, one looking at participation in medical research and the other exploring participation in the decision-making process for health care and therapy. This paper focuses only on the decision-making process for research situations.

The study was funded by a grant from the Program on Ethical Issues in International Health Research at the Harvard School of Public Health.

Study methods

Prior ethical review of the study design was made by the relevant authorities. The Ethical Review Committee of Harvard School of Public Health exempted the study from ethical review because there were no risks to the participants. The study protocol was submitted to ethical review boards of the various Karachi hospitals where the study was planned to be conducted and where approval was obtained in a timely fashion. There were, however, 2 ethical review committees that approved the study on condition that a staff member of their hospital was made a co-principal investigator in the study. This request in itself was deemed unethical by the principal investigator and the study was withdrawn from those institutions. The study was conducted at several other hospitals after due ethical approval and at other sites such as office buildings, schools and public waiting areas after obtaining written approval of the local administrators.

Two research officers, with prior training in the process of conducting interviewer-based questionnaire surveys were employed to conduct the study. Adults of both sexes, who could speak either Urdu or English, were selected and a verbal informed consent was obtained after explaining the nature of the study. People sitting in waiting areas of hospitals, both patients awaiting their turn and their attendants, parents and teachers in schools and office workers were included. The research assistants visited each site for 2–4 days depending on the size of the site and spent from 1–4 hours per day conducting the interviews. The data were entered in Epi-info 6, cleaned and verified for accuracy.

The study had some limitations. It was an exploratory study and did not probe deeply into the sociological reasons of some of the issues that it revealed. An in-depth qualitative analysis would be needed to look deeper at some of the concerns that have emerged as a result of this study. It was also limited to the English and Urdu speaking population and was confined to one major urban city. Groups of lower education status and older age were under-represented because participants were recruited from schools and educational institutions and banks and other workplaces.

Study findings

There were 337 people surveyed: 44% women and 56% men. Their educational status was classified as follows: 20% were educated to class 5 or less (junior school), 36% class 5–12 (middle to high school) and 44% were educated to over class 12 (above high school). The majority (70%) of the participants were aged 21–40 years age, 25% were 41–60 years and 5% were 61+ years. The questions asked and the responses are shown below.

“In your opinion, how important is the process of informed consent before people can participate in medical research?” The first question sought respondents’ general views about informed consent. While 82% of respondents said that the process was important or essential, 16% said taking consent was an optional step and not always necessary.

“How important is it for the participant to trust the researcher as his benefactor?” This question was intended to assess what respondents perceive of the researcher when they go ahead to sign the consent form and whether they actually consider their contract with the researcher to be a trust-based relationship in which they are relying on the researcher as their benefactor. Overall, 63% felt that the researcher was indeed their benefactor, 26% were unsure of the relationship and just 11% felt that they needed more than just blind trust to agree to participate in research.

“How important is the process of documentation of informed consent for the protection of the participants?” The responses to this question showed that 61% of people believed documentation of informed consent was important and essential but 39% felt that it was either unnecessary or optional to document anything.

“Do you think that the researcher should involve the family members or elders of an adult potential study participant in the process of obtaining an informed consent?” It is customary in many developing world communities to go through community gatekeepers to obtain access to the research subjects within the community. For this particular question, opinions were divided: 38% believed it was unnecessary to involve family members or elders in obtaining informed consent, 44% said it was important or essential, whereas 18% said it was optional to involve the family elders.

“In case the research participant is a woman, do you think that it is important to ask permission of her father or husband (in case of a married woman) before approaching the woman?” The majority of the respondents clearly felt that it is important to involve the father or husband when enrolling a female research participant in a trial. Overall, 60% of the respondents felt it is essential that the father’s or husband’s permission be sought before approaching the woman and 17% said it was optional. Only 23% said that this practice was unnecessary. Further analysis of the responses to this question revealed that there was no significant difference in the opinions expressed by male and female respondents regarding the involvement of father/husband of a female research participant. Cross-tabulating against the educational status revealed that the respondents with the highest level of education were the least likely to ask for involvement of the father or husband.

“If the research subject is a woman and the father and husband have already given permission to approach the family, how important is it still to obtain consent from the woman herself?” To further probe the issue of women’s autonomy, respondents were asked about obtaining consent from the woman herself. A majority (74%) said “yes” to this question, indicating that the opinion of the research participant was of paramount importance, no matter what the elders had said.

“In case there is a difference of opinion between the study participant and the family leader (the father or the husband), what is the importance of the participant’s own opinion, if the participant is a man or if the participant is a woman?” This question explored gender differences in opinion among respondents in cases of conflicts between the family elders and the participant. According to the results, if the study participant was a male and he had a conflict with the family, 74% felt that his opinion should prevail over the opinion of the family elders and 10% of the respondents said that his opinion was unnecessary (the remainder were unsure). If the study participant was a woman, however, only 26% of respondents now felt that it was unnecessary to follow the woman participants’ wishes and instead would honour the family elders’ directives, 53% felt that the woman participants’ opinion should be honoured while 11% were unsure. On further analysis, the views of men and women were similar to both sets of the question.

Conclusion

Most of the respondents in this study felt that informed consent was an important step in the process of recruitment of research participants but many felt that it was a trust-based process not requiring proper documentation. Local traditions and norms dictate that while recruiting women, it was important to approach women through their husbands and fathers. While it appears that both sexes have the same opinion on the issue, less educated people placed more emphasis on the father or husband’s involvement than better educated people. In situations where there was a conflict between the opinions of the family leaders and the participants, it was clear that the male participants’ opinion was valued more than the female participants’ opinion by both men and women. This study has raised several interesting issues which require a more in-depth sociological analysis to gain further insight.

References

- Jafarey AM, Farooqui A. Informed consent in the Pakistani milieu: The physician’s perspective. Journal of medical ethics, 2005, 31:93–6.

- Moazam F. Families, patients, and physicians in medical decision making: a Pakistani perspective. Hastings center report, 2000, 30:28–37.