Example of policy issue: zinc supplementation

WHO and UNICEF have issued a joint statement recommending zinc supplementation in under-five children with acute diarrhoea. This is in view of research findings which have shown that zinc supplementation, when given during an episode of acute diarrhoea, reduces the severity and duration of the episode, and when given for a period of 10-14 days, lowers the incidence of diarrhoea in the following 2-3 months.

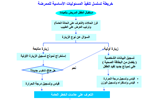

This is the scientific evidence. If a country wants to adopt the recommendation about zinc, it needs to translate it into a comprehensive policy.

There is a need to make a number of decisions, for example those on:

which formulation to use

its inclusion in the national essential drug list

its procurement and distribution

cost policy

budget requirement and allocation

revision of clinical guidelines and relevant training materials

dissemination of information on the policy itself—including briefing of the concerned health officials at different levels and health providers, professional associations and academia, and partners

a mechanism to monitor its implementation and evaluate its effects.

Related links

Health systems support

The implementation of a child health strategy can serve as an opportunity to strengthen selected elements of health systems. At the same time, such a strategy depends on functioning health systems to deliver equitable, quality care and reach those who need it.

About this section on health systems

Strengthening health systems

It has become obvious over the years that unless health systems’ capacity is strengthened, child health programme efforts will not be sustainable in the long-term and it may be difficult to expand coverage of their interventions. Temporary, ad hoc initiatives may initially work but are short-lived.

As functioning, equitable and effective health systems are a requirement for quality care of essential services and their sustainability, strengthened health systems are essential for the achievement of the health-related Millennium Development Goals.

The issues of major concern are substantial, as they relate to planning and management, human resources, financing, drug supply, etc., and have a considerable effect on child health programme activities.

This is the reason why two of the three components of the IMCI strategy (Integrated Management of Child Health) deal with health systems: the 1st component, which emphasizes the importance of human resource development in child health, and the 2nd component, which deals with health system support.

Plans for improvement of both the components should be developed at the same time. An IMCI training initiative to upgrade health providers’ case management skills (IMCI 1st component) without proper preparation of the health system (IMCI 2nd component) is not considered an “IMCI strategy” and is unlikely to have significant and lasting impact.

The IMCI strategy also calls for the establishment of strong links between health systems and the community (IMCI 3rd component). As emphasized in an intercountry workshop on the IMCI community component, community health workers are seen as an integral part of the public health system, a ‘bridge’, or even an extension of the primary health care facility into the community and also of the community into the health system.

In this Region, the Child and Adolescent Health and Development Programme (CAH) has promoted the importance of health systems as part of a child health strategy. It has developed tools to standardize the process. It has been possible to strengthen selected aspects of health systems through the IMCI strategy in countries with a functioning health system.

A child health strategy cannot on its own strengthen or reform the whole health system. However, it can contribute to improving selected aspects of it, setting priorities, allocating resources, developing tools, raising key issues and working closely with the sectors responsible for health system support elements to propose and find long-term solutions. This is needed to achieve an acceptable level of performance and coverage, and sustain it over time.

The Regional office has also launched an initiative to assist countries in developing national child health policies. Such policies are meant to go beyond the specific technical guidelines of each programme component and aim to address also major issues such as human resources and financing. This approach is critical to create favourable conditions to expand interventions and reach those in most need, the poor and disadvantaged families.

Child health policy initiative

Intercountry workshop on the IMCI community component

Quality care

If “coverage” is an important aim of public health interventions, “quality” is another key, leading principle. Only care of affordable, sustainable high quality standards can produce good results for the health of individuals. Investing in quality means having high returns in the long term.

The challenge in public health is often that of finding the right balance between “quantity” and “quality” of activities, to have impact within an acceptable period of time.

It is essential to define minimum standards of quality care and quality activities: the pressure to increase coverage should respect such standards. When quality is sacrificed and standards fall below the minimum originally set, then the investments made are likely to be ‘lost’.

What characterizes the IMCI approach in the Region is the stress placed on quality. Clearly defined and agreed upon quality standards are set in each country for key IMCI activities (from planning to implementation and evaluation). Measurable indicators are selected and monitored to ensure that standards are met throughout implementation.

There is global and regional evidence that this approach gives results, improving health provider performance, the use of drugs, caretaker satisfaction with services received and their utilization. The cost of care may then even be reduced, as resources are more effectively used. Thus, investing in quality may bring savings, in addition to better care.

About this section on health systems

This section of the website provides some information on the work carried out in the Region to strengthen health system support elements for the delivery of quality child health care services. It is not meant to be a review of health systems.

A short description of health system issues affecting child health programme performance is provided under each topic as an introduction to the work specifically undertaken by public child health programme managers in the Region and the CAH unit of this Regional office to address them.

Additional information on work carried out in this area by individual countries, including some of the tools developed, is available in the section on implementation.

Key issues in the area of health systems to be considered when planning for IMCI are described in the IMCI planning guide developed by CAH headquarters.

Additional information on health systems

Policy, planning and management

Policy

A policy-supportive environment is essential to both the implementation and sustainability of public health interventions. Mechanisms should also be formally agreed and in place to monitor the implementation of such policies, evaluate them against the original objectives for which they were developed, and update them as needed.

Child health initiatives are no exception. For example, the incorporation of the principles and elements of IMCI (Integrated Management of Child Health) in key strategic documents and the updating of existing policies or the development of new policies to support IMCI implementation in the long-term is critical to achieve and sustain the child health outcomes for which specific interventions were designed. See an example of how essential policy decisions support effective child health care interventions.

A few countries in the Region have included IMCI as a key strategy in their national health development plans or similar documents which set mid-term or long-term directions.

During the process of country adaptation of the IMCI strategy when policies and guidelines are usually reviewed to ensure consistency, it was observed that many countries lacked written policies or had child health-related policies or guidelines scattered in different policy or training documents, often by programme.

This observation and the need felt in countries to have a national child health policy document, led the Regional office to launch the Child Health Policy Initiative. The initiative aimed to assist countries in developing national child health policy documents.

As part of this initiative, the Regional office developed the document “Development of National Child Health Policy – Phase I: The situation analysis” in September 2004, to guide countries in this phase, taking into consideration the experience gained in the Region.

Given the importance of the topic, a full section of this website is dedicated to the Child Health Policy Initiative, to which the reader is referred for more information and details.

Child Health Policy Initiative

Development of National Child Health Policy – Phase I: The situation analysis

Management

The presence of a child health management structure at central and implementation levels facilitates the implementation of public child health programmes and interventions in developing countries, more so when under-five mortality rate—a key development indicator—is high.

In these situations, the management structure should preferably be reflected officially in the ministry of health organigram, with clear identification of responsibilities of staff at different levels. This helps to support the sustainability of any improvements in child health outcomes in the future.

The specific emphasis on child health is largely justified by the fact that investing in the health and development of children means investing in the future development of a nation.

Some countries in the Region have designated full-time focal points or ‘programme managers’ for child health, including IMCI—Integrated Management of Child Health (e.g. Egypt, Sudan, Tunisia and Syrian Arab Republic). This decision gives more visibility to child health, facilitates the allocation of funds to its interventions and the coordination with other programmes within the ministry of health and with partners, including donors.

The existence of a committee at national level with representatives and resource persons from other child health-related programmes, professional associations, teaching institutions and partners, improves also coordination and supports advocacy initiatives, as the experience with IMCI has shown in the Region. For example, involvement of key paediatricians and teaching faculty of medical schools in the adaptation of the IMCI clinical guidelines has raised interest in the IMCI approach among selected medical schools and led to its formal incorporation in the teaching of medical students in several countries.

Planning

The development of sound plans with indicators and targets is a pre-requisite for a successful implementation of activities.

Plans need to rely on a thorough situation analysis in order to be responsive to needs.

Countries implementing IMCI in the Region such as Egypt, Syrian Arab Republic and Tunisia reviewed the quality of child health services at health facilities in districts selected for IMCI as a standard approach before starting implementation. This helped to identify resources, strengths and weaknesses to be addressed in planning and to compare information collected after IMCI implementation with the baseline information, to measure intermediate outcomes.

As an alternative approach, Morocco and Sudan compared performance of districts implementing IMCI with districts not implementing IMCI.

As part of the situation analysis, most countries focused on the need to prepare health facilities for implementation.

Countries such as Egypt also reviewed health system issues at district level, such as the management structure and capacity, human resources, policy on exemption of fees for clinical follow-up visits, drug management, referral, supervision, health information system, and training capacity, including training facilities and caseload.

Since IMCI implementation is a decentralized process, planning skills need to be strengthened at implementation level.

A systematic approach to IMCI district planning, described in “Guide for district planning workshops” (in Arabic), was followed in Egypt to improve the planning capacity for IMCI implementation of the district team. The objectives of these workshops, which convened all the concerned governorate and district health authorities, were to develop a feasible plan for implementation in the district, ensure the commitment of health officials at that level, and build planning capacity through this guided process. Similar workshops were conducted in Pakistan, Sudan, Syrian Arab Republic and Tunisia.

The Regional office has developed a "Guide to planning for implementation of IMCI at district level", mostly based on the rich experience from Egypt, reviewed by a team of experts with large field experience and tested, as a reference for other countries in the Region. The Guide includes a library of practical, useful tools for adaptation and use by countries.

Related links

Preparing the health facility for IMCI implementation

Systematic approach to IMCI district planning, Egypt

Guide to planning for implementation of IMCI at district level

Third intercountry workshop on the child health policy initiative, 10–13 December 2006

Second intercountry workshop on the child health policy initiative, 13–16 November 2005

Intercountry workshop on child health policy development, 26–29 July 2004

Financing

Adequate financing of the health sector is key to functional, equitable and sustainable health systems and provision of effective, quality care services. It is therefore an important determinant of population health and a key element of poverty reduction strategies.

If universal coverage of essential services is the underlying aim, this means that people must have access to essential health care services at a cost they can afford.

Costs of essential health care services, including the payment of consultation fees, drugs, laboratory tests and other services, may act as a major barrier to utilization of health services, especially by those who most need them, the poor and disadvantaged families. As a result, children, who represent the future of any society, may pay a high price, their health and development being at high risk unless effective care is made available to them.

Strategies to improve child health care must therefore consider not only the purely technical aspects of care but also the implications that any factor that has an impact on equitable access to care has for the health of children.

While policies can address the issue of financing, public child health managers can contribute to studying, proposing, advocating and implementing approaches that improve access to essential, quality child care.

There are examples of important initiatives undertaken by countries in the Region when implementing IMCI (Integrated management of Child Health), as part of their strategy to improve child care. In Egypt, drugs needed to treat the prevailing child conditions according to the IMCI guidelines were provided for free, including pre-referral drugs (with some exceptions, such as health facilities covered by the health insurance scheme). In the Syrian Arab Republic, a ministerial circular was issued to direct health facilities implementing IMCI to provide drugs included in the IMCI protocol for children under 5 years old for free. Both countries also implemented a policy of exemption from fees for clinical follow-up visits, after the introduction of IMCI: children with conditions needing to be followed up were exempted from the consultation fee for the repeat visit for the same episode, to promote timely follow-up. In the Islamic Republic of Iran, the IMCI guidelines were used as reference standards for reimbursement through the health insurance scheme.

Human resources

A critical issue

Human resources and their development are the backbone of any health system. It is people who manage and deliver health care services to the population. They must be competent, motivated and effective in carrying out their tasks.

Much emphasis has been given in the past by many vertical programmes to improving health staff competencies, to provide them not only with the knowledge but also with the skills required to discharge their functions. In-service training has often been seen as the “solution” to problems in care delivery.

While upgrading health staff skills is critical, there are a number of other important issues related to human resources that need to be addressed to improve not only health providers’ provision of better services in the long-term but also to ensure their presence where they are most needed.

Improving pre-service education has the potential “to produce” more competent health cadres for the tasks they will need to carry out in a more sustainable way.

“Production” of human resources, however, needs also to be tailored to country and geographical needs.

Addressing the issue of human resources is critical to ensuring access to services, their performance and sustainability. The Regional office for the Eastern Mediterranean has therefore been encouraging countries to develop child health policies which address also the issue of human resources, to create a favourable environment for the delivery of quality child care.

Attention is drawn to the management, production and in-service capacity building of human resources, as outlined below.

Management

Management of human resources is of vital importance.

It includes among others:

good coordination mechanisms between the ministry of health and the ministry of education;

health provider distribution plans by category and area, to ensure access to care according to area needs;

motivational schemes and transfer policies to attract and retain health providers in the public health sector, guarantee continuity of services and reduce absenteeism, and decrease their high turnover, especially after in-service training; and

maintaining a database on trained staff.

As an example of actions taken to address the issue of high turnover of trained staff, a ministerial circular was issued in the Syrian Arab Republic requesting health providers trained in IMCI to remain assigned to the same facility for at least a year after the training and until they could be replaced by another provider also trained in IMCI.

In addition to the review of some of these concerns by some countries during the introduction of the IMCI strategy, the child health policy initiative is seen as an important undertaking and opportunity to address these issues with more action-oriented policy commitment.

Production

Pre-service education is the first step of human resources’ professional development and a key investment for long-term sustainability of quality interventions.

Pre-service education also prepares health professionals for both the public and private sectors, offering a unique opportunity to provide them with the same basic knowledge and skills and influence their attitudes.

Education needs to be of high quality, properly funded, regularly evaluated, tailored to priority public child health needs based on epidemiological evidence, and geared to ‘produce’ cadres of health professionals proportionate to needs and based on a clear production planning policy.

This Region has been pioneering initiatives to enhance the teaching of child health elements in pre-service education in medical and allied health professional schools, with great emphasis on a skill-based approach to the outpatient management of child illness and health.

In-service training

In-service training is the area which has most often been supported over the years, usually through external financial support.

In-service training remains a major component of the IMCI strategy, for which a standard training package and approach have been developed and used in countries implementing IMCI.

Indicators for quality training have been developed in countries and monitored to keep training up to the set standards.

Despite this, many issues remain: in-service training as an approach needs to be conceived together with interventions addressing also management of human resources and pre-service education, as described above.

In-service training should eventually become an approach to upgrade health provider knowledge and skills rather than fill in existing weaknesses in pre-service education.

High turnover of trained staff in certain countries also requires a continuous training process to ensure the maintenance of the same level of training coverage.

A policy on in-service training would clearly identify priority training areas and financial resources, and be the basis for training plans, to be closely coordinated with sectors and partners involved at all levels.

Currently, the resources to fund most in-service training in child health programmes and IMCI in most countries in the Region have come from donors and international agencies. This makes their future uncertain when such resources decrease or become unavailable. On the other hand, there are also examples of a strong commitment to training in IMCI, like the one from Oman, which used its own funds to support it.

Another issue is the duration of IMCI training, which lasts for 11 days in its standard format. The course follows an approach which includes much exposure to clinical practice, to enable the participants to strengthen their clinical and communication skills. However, this duration causes health providers to be away from their facilities for a relatively long period of time—almost two weeks, including travel time, makes the cost of each course substantial and tends to limit the speed at which a higher coverage can be attained in the country. It is also demanding for the facilitators.

Alternative approaches have been introduced and tried in a few countries in the Region to reduce the duration of IMCI courses. When developing alternative approaches, an effort has been made to ensure there is no compromise on the quality standards of training, which must respond to the same quality criteria of the 11-day training. Inevitably, the amount of clinical practice provided in a shorter course decreases. However, it should be noted that these approaches have targeted physicians, i.e. a category of health professionals expected to have good clinical background in these countries.

The approaches have been very country-specific and therefore cannot automatically serve as models for other countries, especially when the contexts in which they have been introduced differ.

The shorter IMCI courses for physicians include:

a seven-day course introduced in Egypt, after several years of implementation of the 11-day course and the development of experienced cadres of facilitators; and

a 9-day course in Tunisia.

Follow-up visits after this IMCI training have yielded encouraging results. More standard evaluations are needed to document their effectiveness.

Some countries, such as Egypt, Syrian Arab Republic and Tunisia, have also developed shorter, 4-day competency-oriented IMCI training courses for selected categories of health providers (e.g. nurses), emphasizing in training the practice of those skills required for the newly assigned tasks (e.g. triage of sick children).

IMCI clinical training for nurses, Egypt

Triage of sick children at health facilities

Organization of work at the health facility

Rationale

Introducing a quality care intervention in a health facility requires a good situation analysis to plan for all its key supporting elements, in order to prepare the facility for implementation.

It is also recognized that adhering to the IMCI protocol (Integrated Management of Child Health) to manage a child under 5 years old takes time. This may be a constraint in a busy facility with a high case-load if all tasks are carried out just by one health provider with no sharing of responsibilities with other staff at the same facility.

The issue is then how to deliver the whole scope of quality child care efficiently rather than how to shorten the clinical process and miss some aspects of health care. In fact, all aspects of child care recommended in IMCI are important to promote child health and should be included in the management of each child.

One approach that has been used in the Region is the re-organization of the work at a health facility where more than one health provider works—including physicians, medical assistants, nurses, midwives, health volunteers, etc., re-distributing tasks in order to deliver quality care efficiently within the available resources. Three key steps have been identified for this purpose (see below): triage, clinical management and counselling.

Triage

When sick children are taken to a health facility, they should be quickly assessed for a number of danger and severe signs to identify those who are severely ill and who need to be seen by the physician or medical assistant without any delay. For example, a child who is lethargic or unconscious, unable to drink or breastfeed, having convulsions or 'vomiting everything' needs urgent attention.

The basic skills to perform these tasks can be taught in a training course for paramedical staff which specifically focuses on triage.

Other tasks can also be carried out before the child is seen by the clinician, such as weighing, taking the temperature, checking the immunization status, etc. Children who are (very) low weight-for-age and require feeding counselling are in this way identified in advance, as are those who are febrile and require assessment of specific signs and symptoms.

Selected categories of health providers have been trained in newly assigned tasks in shorter and competency-based courses in some countries, such as Egypt, Syrian Arab Republic and Tunisia.

The pre-screening of sick children, achieved through training and re-distribution of tasks, saves time and may have a positive effect on the overall management of the child.

Clinical management

It is very helpful to integrate clinical protocols as much as possible. In fact, the health provider who delivers services at primary health care level is usually the same person, irrespective of whether the guidelines come from one programme or another.

This effort towards integration of clinical management guidelines has been a characteristic of IMCI. IMCI uses a holistic approach to the management of the child and the guidelines guide the health provider through the key steps of the clinical process, from assessment to classification, treatment and counselling.

If triage of children is performed, the physician or medical assistant can then use his or her time to concentrate on the clinical examination of the sick child and prescription of treatment.

Country-adapted IMCI protocols are currently followed as the standard for the management of under-5 children in countries and areas in which IMCI is being implemented.

To emphasize the importance of counselling as a key task in case management, many countries in the Region request the physician or medical assistant to carry out this task as part of the IMCI approach, while in others this is delegated to paramedical staff. The decision as to who should carry out this task depends also on the staffing situation at the health facility.

Country-adapted IMCI guidelines

Counselling

Counselling caretakers of children is a key aspect of the overall management. Most child care is delegated to child caretakers at home, whether it is related to the administration of drugs (e.g., antibiotics, antimalarials, oral rehydration salts, etc.), feeding, administration of fluids, or timely care-seeking. Thus, caretakers need to be properly counselled.

Counselling requires interpersonal communication skills that are often either not or inadequately taught at medical and allied health professional schools. It is often perceived by health providers as a time-consuming and less important task.

The result is that caretakers are often poorly advised on how to care for their children at home and unlikely to care for them properly, as surveys suggest.

Despite the consultation with the health provider, then, the child may not receive proper care, the outcome may be poor, more consultations may be required as the child's condition does not get better or worsens, and some of the family and health system resources invested will have been wasted.

IMCI training and follow-up emphasize the importance of counselling. Counselling can be performed by the physician or medical assistant themselves, or by other staff available at the facility, such as nurses, nutrition educators, health volunteers, etc., after proper training.

Given the importance that nutrition counselling plays in child health, the Regional office’s Child and adolescent health and development programme has undertaken a revision of the WHO training materials on breastfeeding counselling, based on regional experience in conducting these courses. The training materials on “Counselling on Infant and Young Child Feeding” include also a section on complementary feeding and feeding in special circumstances. They are currently available in Arabic. There are plans to translate them into English.

Regional training materials on "Infant and Young Child Feeding Counselling"

Preparing the health facility

It is important to prepare the health facility before staff are trained in IMCI, to ensure that clear responsibilities have been assigned to the staff at the facility and work has been organized and rearranged to reflect the case management tasks that are taught in the training course according to the IMCI guidelines.

This preparatory work is strongly advocated in the Region. Preparation has included the following steps in several countries (see section on IMCI implementation for individual country experiences):

reviewing staff’s responsibilities;

re-arranging the flow of patients;

making drugs and key supplies available; and

central or district team’s monitoring of the preparatory work, to support the process and ensure that facilities are ready for implementation.

The flowcharts developed in Djibouti, Egypt and Tunisia as part of IMCI are examples on how work is organized at a facility in which IMCI is implemented: the flowcharts refer to all children taken to the facility as an entry point, whether they are taken for an illness or to the well-child clinic.

Organization of work flowchart, Djibouti

Organization of work flowchart, Djibouti  Organization of work flowchart, Egypt

Organization of work flowchart, Egypt  Organization of work flowchart, Tunisia

Organization of work flowchart, Tunisia

Medicines, vaccine and supply management

The availability of medicines and vaccines is critical to the provision of quality care. The impact of training a health provider on the clinical management of common childhood illness is likely to be minimal if, after training, the health provider lacks, in his or her own health facility, the supporting means of applying what he or she has learnt, such as essential medicines, or if the sick child does not have access to those medicines.

Essential medicines need to be of assured quality, regularly available and affordable to those who need them, especially the poor and disadvantaged who are the most vulnerable to illness.

In line with the principles of the essential medicines concept, country-adapted IMCI guidelines (Integrated Management of Child Health) include a limited list of key drugs for the outpatient management of priority health conditions in children under-5. Where national essential medicine lists exist, these have been reviewed to ensure that the medicines recommended in the IMCI guidelines are also included there, for the different levels of the health care system and for use by the categories of health providers targeted by IMCI.

IMCI follow-up visits and surveys conducted in the Region have shown some improvement in availability of medicines in facilities implementing IMCI. However, they have often described also problems in availability of injectable pre-referral medicines and second-line antibiotics. Making essential medicines regularly available and at an affordable cost remains a major issue in many settings.

A more appropriate use of medicines—especially antibiotics—by IMCI-trained health providers have also been described in the Region, similarly to that shown in the IMCI multi-country evaluation. This contributes to reducing waste and improving drug availability for those cases which really need them. It ensures that limited resources are properly used, whether they are provided by the health system or come from the household.

Within the context of IMCI, Egypt developed a “drug management package” as training aid for personnel managing medicines at health facilities and district level. This has been a collaborative effort of the CAH (Child and Adolescent Health and Development) and EDB (Essential Drugs and Biologicals) programmes of the Regional office, and the Pharmaceutical department and the General Administration of Childhood Illness Programmes of the Ministry of Health and Population, Egypt.

As with medicines, vaccines also need to be regularly available, together with the equipment and supplies required to store and deliver (cold chain) and administer them (syringes, needles) properly.

The IMCI guidelines recommend routine screening for immunization status of any child taken to a health facility—whether sick or healthy, in order to increase opportunities for immunization, in line with national immunization policies.

In addition to water and medicines, the list of other supplies required for IMCI at primary health care is short. It includes basic items, such as items required to weigh the child and take his or her temperature, count the respiratory rate, prepare oral rehydration salts (ORS) solution, counsel the mother (home care counselling card) and record and report information.

The preparation of health facilities before the health providers are trained in IMCI and the systematic conduct of follow-up visits after IMCI training at the trainees’ health facilities provide the means of checking whether the supporting health system environment is in place to enable the trained health provider to deliver quality child health services. It also helps raise issues with the local district authorities for further follow-up.

Information on the availability of medicines, vaccines and other supplies is also collected during IMCI health facility surveys and described in the related reports.

Essential Medicines and Pharmaceutical Policies

Priority life-saving medicines for women and children

WHO model list of essential medicines for children

Country-adapated IMCI guidelines

List of medicines included in the IMCI guidelines by country

National immunization policies in the IMCI guidelines

Referral

Referral care represents an important step in the management of the sick child.

One of the key aspects of the IMCI training is that the primary health care provider is trained to recognize children with severe conditions who require urgent hospital management. These situations are considered medical emergencies at that level of the health system.

System and community support to referral

Referral for breastfeeding problems

Pre-referral treatment

The health provider is therefore trained to administer any pre-referral, urgent treatment as needed, to reduce the delay in initiating treatment at the referral site caused by the long time that the referral process may take. Many deaths in severe cases occur in fact on the way to the hospital or during the first 24 hours of hospitalization.

The provider also plays an important role in advising and supporting the sick child’s caretakers, to explain the need for taking the child to a hospital without delay and overcoming existing cultural barriers.

Emergency triage assessment

Emergency triage assessment—for rapid screening of sick children upon arrival at a hospital—and treatment is a key area of referral management. A training course has also been developed by WHO on “Emergency Triage Assessment and Treatment (ETAT) course”.

This area is also emphasized in the guidelines for care at the first-referral level in developing countries, consistent with the IMCI (Integrated Management of Child Health) approach for outpatient care, that WHO has developed as a reference manual: “Management of the child with a serious infection or severe malnutrition”. The Regional office has translated the document into Arabic to make it available to a wider audience in the Region.

The aim is to provide immediate emergency treatment where needed, give priority to severe cases over other waiting patients, and distinguish emergency and priority cases from those who do not need urgent care.

A pocket-size manual on hospital care for children has also been developed by WHO for inpatient care of major causes of childhood mortality in small hospitals in countries with limited resources. The book has been translated into more than 20 languages.

Emergency Triage Assessment and Treatment (ETAT) course

Other issues concern the provision of feedback from the referral unit to the referring health centre.

When referral is not possible

More complex is the situation in which referral is not possible, which remains insufficiently addressed.

Families, especially the poor and disadvantaged, may find it difficult to find the resources to afford transportation to the referral site—when transportation is available—and all other related expenses in case of hospital admission of the child, unless financing schemes exist and community resources are mobilized.

Mothers, the primary source of childcare in most cases, have commitments also to other family members, may need to engage in income-generating activities to support their family, and may be unable to keep the child at the hospital as necessary. Perception of the quality of care provided at the referral level may also be low and influence the decision toward managing the child in the community.

System and community support to referral

These and other issues clearly underline the importance and need to address together health system issues (e.g., health financing to guarantee equitable access also to hospital care) and community issues (e.g. support mechanisms), in addition to clinical care. They support the view that child care should be seen and implemented comprehensively rather than as a series of vertical programmes or independent interventions.

While the referral hospital is expected to provide higher-level management of severe cases, in reality this often requires further upgrading of its staff’s clinical management skills. Referring a child is, therefore, only part of the solution.

Referral for breastfeeding problems

A particular area of referral is that concerning mothers with breastfeeding problems.

As part of the IMCI strategy, some countries implementing IMCI also provide training in breastfeeding counselling to a number of health providers from selected health facilities, to further enhance their counselling skills and capacity in managing breastfeeding problems of referred mothers.

In general, referral care remains a weak area and much more work is needed to address the issue.

Management of the child with a serious infection or severe malnutrition

Pocket book of hospital care for children

Health information system

A key component of any health system is health information. This is essential to inform policies and the planning process.

To be useful, data need to be:

easy to collect—rather than require too much time from health providers,

reliable, to be provided in a timely manner across the system,

transformed into information for use for decision-making, and

fed back in a user-friendly format—preferring maps and graphs rather than tables whenever possible—to those who collected it, for use also at their level.

Monitoring the quality of data collected and providing immediate feedback, e.g. during supervisory visits or programme mangers annual meetings, is also an important aspect of data management. Experience suggests that the process of feedback is critical to improve reliability of data recording and reporting.

Unfortunately, health information systems (HIS) often suffer from many weaknesses. Furthermore, vertical programmes may often develop their own recording forms and reporting systems to monitor programme performance more closely and in detail. This unfortunately also translates into overburdening an already malfunctioning information health system.

At the end of the line, there is always one health provider who is supposed to take care of everything: this reality should guide decisions, even if that means foregoing ambitious systems. It is then important to find the right balance.

When introducing IMCI (Integrated Management of Child Health), many countries in the Region have felt the need to collect information to monitor implementation and performance of intermediate outcome indicators. One of the challenges has been to make the IMCI action-oriented classifications at primary health care level compatible with the disease-oriented HIS classifications.

Usually, countries have introduced in health facilities the IMCI clinical recording forms used during IMCI training courses, as health providers have been trained in their use and find them a useful guide to the clinical management of a child.

Based on those forms, some countries (e.g. Egypt, Djibouti, Sudan, Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia) have introduced or modified registers for under-5 children, with information due to be summarized and reported to the higher level monthly.

In some cases (e.g. Egypt, Djibouti, Syrian Arab Republic) HIS classifications have been modified to include the IMCI classifications, simplifying the recording and reporting job at primary health care level. These approaches need to be evaluated.

Supervision

Supervision plays a key role in maintaining the quality of performance of health providers and the services they deliver. Supportive feedback is also highly valued by health providers and helps motivate them in their work.

However, routine supervision is one of the weakest areas in many developing country settings. Lack of transportation means, fuel, financial resources, as well as inadequate training in supervisory skills, approach to supervision and supervisors’ attitudes are some of the constraints reported to supervision.

WHO child health-related programmes have over the years promoted the concept of supervision as supportive supervision and an opportunity for strengthening services, including clinical management, to replace the deeply rooted idea of supervision as “inspection” or a purely administrative task.

The standard approach to follow-up visits after IMCI training (Integrated Management of Child Health) has been used in all countries implementing IMCI in the Region to both reinforce health provider skills and improve health system support elements at the health facility. Findings of the visits are not only discussed with facility staff but also usually reported to district health officials for supportive action.

However, IMCI-trained health providers receive only few follow-up visits (one to two on average), within the first few weeks and/or months of training. Follow-up visits then leave the place to routine supervision, which should further improve or at least maintain the levels and standards of care achieved initially.

Information from reviews and data from IMCI health facility surveys suggest that much needs to be done to improve routine supervision. According to those findings, the frequency of supervision varies remarkably from place to place; only a small proportion of facilities visited receive clinical supervision and have the findings recorded in a supervisory book as a reference for the facility staff and future follow-up.

Efforts to improve the quality of supervision in child health have been made by selected countries. Integrated supervisory checklists have been developed in several countries (e.g. Djibouti, Egypt, Islamic Republic of Iran, Sudan, Syrian Arab Republic, Tunisia) to standardize the child health component of routine supervision, although their effects still need to be properly evaluated.

A supervisory skills training package has been developed in Egypt for governorate, district and health facility levels.

Developing checklists and training supervisors in their use is however only one of the issues. Supervision requires, as seen also for other health system elements, a more comprehensive approach.

Client satisfaction

Client satisfaction is an important determinant of health service utilization. Essential, quality health services need to be not only universally accessible but also utilized by those for whom they are meant.

Client satisfaction includes aspects of quality care defined both in the way they are traditionally regarded by health professionals (e.g. good clinical management practices, availability of drugs, etc.) and as they are perceived by the community (e.g. waiting time, interaction with provider, etc.).

There is evidence that for facilities in which IMCI (Integrated Management of Child Health) is implemented, child caretakers (the “clients”) are often satisfied with the services received. Results of the global IMCI multi-country evaluation show that IMCI introduction has been accompanied by an increased utilization of facility-based outpatient child health services.

Most countries in the Region have included questions on caretaker satisfaction in their standard follow-up visits to health providers after IMCI training. The findings often show a good level of caretaker satisfaction.

Similar findings have come from the IMCI health facility surveys. Much appreciated by caretakers is the way children are examined by the IMCI-trained health provider, the treatment and the information given, and provider’s attitude. All these aspects are an integral part of the IMCI approach, which, when properly implemented, can therefore contribute to making health services more attractive to the clients and improve their reputation.

Evaluation and research

Evaluation

Evaluation plays an important role in child health and, more in general, in public health. Progress towards the targets originally set needs to be monitored periodically to see whether strategy implementation is moving in the right direction and to revise plans according to the findings.

Before countries start expanding activities related to IMCI ( Integrated Management of Child Health) in the country, they conduct a formal review to summarize the lessons learnt and plan for expansion based on the findings. Most countries in the Region have over the years conducted such reviews in close collaboration with the Regional office.

The Regional office has also recommended that countries periodically review programme implementation also during the expansion phase, especially when a substantial proportion of health facilities has been covered. It has proposed for this purpose an approach which includes the preparation of a background document followed by the conduct of a workshop.

Data collected during follow-up visits carried out after IMCI training are also used as database to monitor health provider and health system performance in facilities which implement IMCI.

Once a sizeable number of health facilities has been covered in a country during the expansion phase, a few countries have carried out health facility surveys on the quality of outpatient child health services, or IMCI health facility surveys, in close collaboration with and with full support of the Regional office. The methodology has been adapted in the Region, to better respond to country needs and analyse in detail the information collected.

These surveys, in the way they are carried out in the Region, provide a substantial amount of both quantitative and qualitative information that is useful to re-direct priorities and implementation as needed, revise plans and advocate for policies.

It is hoped that more financial resources will be made available to child health in the future, to enable the conduct of evaluations also in other countries which have expressed interest in them. This helps document with hard data the performance of outcome-oriented indicators and, indirectly, also health system progress towards the Millennium Development Goals.

Research

Research is a key area of development. Most of the priority research in child health in WHO is coordinated by the WHO headquarters in Geneva.

The Regional office has recently embarked on some research work to address emerging child health problems in the Region, such as injuries, and thus respond to country needs.

A new initiative has also been launched on a trial basis to identify priorities for “implementation research” to reduce neonatal and child mortality in selected countries in the Region. The process follows the systematic Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative (CHNRI) methodology and aims to identify and prioritize the barriers to implementation of public health interventions aimed at reducing deaths in neonates and children in the country.